By Jesse Newman and Annie Gasparro

The coronavirus pandemic is deepening challenges for the U.S.

food system, forcing plant closures and infecting farmworkers at a

time when packaged-food companies say demand for groceries has

never been higher.

Production has been curtailed at a range of facilities across

the country, including a Kraft Heinz Co. macaroni-and-cheese plant

and a Conagra Brands Inc. frozen-meal factory. At the same time,

food companies are instituting precautions to maintain or restore

production so they can to keep grocery stores stocked.

Conagra said 20 of the 700 workers at its factory in Missouri

that makes chicken pot pies and other frozen meals had contracted

the virus, prompting the plant to close for 10 days beginning April

17. A spokesman said the company needs the time to conduct a deep

cleaning and prepare more rigorous preventive measures for when

employees return to the plant.

Flowers Foods Inc. said it closed a baking plant in Tucker, Ga.,

for a few weeks this month after workers tested positive for the

virus. The company, whose brands include Wonder Bread and

Tastykake, wouldn't say how many of the plant's 255 workers were

sick.

The disruptions come amid heightened worry over the nation's

food supply chain as illnesses close meatpacking plants, curtailing

output of chicken, beef and pork and limiting supplies at grocery

stores. Pork giant Smithfield Foods Inc. has shut down its Sioux

Falls, S.D., plant, which with hundreds of infected workers has

become a major coronavirus hot spot.

To help shore up the food supply chain and help farmers hurt by

collapsing commodity prices and restaurant demand, the Trump

administration last week pledged to spend $19 billion in direct

payments to farmers and ranchers as well as government food

purchases.

Even as the new coronavirus forces more plant closures, some

facilities that had been closed because of the outbreak are

reopening. In Pennsylvania this week, meatpacking facilities run by

Cargill Inc., JBS USA Holdings Inc. and Empire Kosher Poultry Inc.

will ramp back up with new safeguards. The measures include

footprints painted on the floor to mark recommended distances

between employees, and tents set up for extra cafeteria seating,

company and union officials said.

Food makers outside the meat sector were initially able to avoid

factory closures when the coronavirus began spreading throughout

the U.S. in March. They say the production process for packaged

food is typically more automated than work done on farms,

slaughterhouses and meatpacking plants.

Companies such as Kraft Heinz, Danone SA and General Mills Inc.

also took safety steps, including taking workers' temperatures and

slowing production where necessary to allow for wider spacing and

fewer workers on manufacturing.

Nonetheless, packaged-food executives are growing concerned

about mounting illnesses at their plants and those in their supply

chain.

"Everyone is most worried about factory workers," said Patrick

Criteser, chief executive of Tillamook County Creamery Association.

"We can find different packaging-materials or raw-materials

suppliers, but we need those plants to keep operating."

Tillamook, a dairy cooperative based in Oregon, has implemented

new safety measures in its plant, which helped keep the one

Covid-19 case recorded there from infecting more people. That

employee has recovered from the coronavirus disease and is back at

work, Mr. Criteser said.

Kraft Heinz's macaroni-and-cheese factory in Springfield, Mo.,

reported two Covid-19 cases last month and closed for a few days

for cleaning. Campbell Soup Co. said its Pepperidge Farm bakery in

Denver, Pa., had five cases and "paused certain operations" for a

deep cleaning. A Frito-Lay factory in Modesto, Calif., shut down

for a couple of days for a deep cleaning after an undisclosed

number of workers contracted the virus. Frito-Lay, owned by PepsiCo

Inc., employs 600 people there.

Workers are also falling ill on farms that supply packaged-food

companies. Three agricultural workers in Cayuga County in western

New York, for instance, tested positive for the new coronavirus,

one of whom -- a man in his 40s who worked on a dairy farm -- has

died.

The department says it has conducted contact tracing on farms

and that a team of nurses has traveled to farms to test symptomatic

employees.

A North Carolina farmworker also tested positive, according to

an email from a regional health clinic viewed by The Wall Street

Journal. The worker was quarantined and is recovering, the email

said.

The regional clinic has prepared hundreds of Covid-19

information packets in English and Spanish, as well as handmade

masks and a supply of gloves, for distribution to farmworkers

through a faith-based group. The clinic is planning a Zoom

conference for local farmers to provide information about the

pandemic and is opening its coronavirus help line to farmers.

Across the country, the busy spring season is starting to bring

thousands of workers to farms where they live and work in close

proximity to one another. In North Carolina last year, nearly

22,000 migrant workers, largely from Mexico, joined others on farms

to harvest crops including tobacco, sweet potatoes and

cucumbers.

Some farms and labor contractors have been working to prevent

the virus's spread by checking migrant workers' temperatures before

they cross the U.S.-Mexico border, spacing workers further apart in

fields and delivering groceries to housing camps.

The Trump administration in recent weeks has taken steps to make

it easier for farms to hire migrant workers. It also pledged $16

billion in payments to farmers and ranchers and $3 billion in mass

commodity purchases to be distributed through food banks.

Cattle ranchers, dairy and hog farmers are set to receive $9.6

billion in direct payments, while row crop farmers will receive

$3.9 billion and specialty-crop producers will get $2.1 billion,

according to John Hoeven (R, N.D.), chairman of the Senate

Agriculture Appropriations Committee.

Farm groups welcomed the relief program, but said it isn't

enough to offset plunging commodity prices and demand from

restaurants. Hog farmers will receive $1.6 billion in direct

payments, though the National Pork Producers Council estimates

industrywide losses for the rest of the year will total $5 billion

as farmers lose $37 per hog they market.

Joe Glauber, former chief economist at the U.S. Department of

Agriculture, said also that he had hoped some federal funds would

be dedicated to preventing illnesses in the nation's food

plants.

--Jacob Bunge contributed to this article.

Write to Jesse Newman at jesse.newman@wsj.com and Annie Gasparro

at annie.gasparro@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 20, 2020 15:03 ET (19:03 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

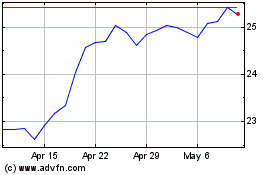

Flowers Foods (NYSE:FLO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Oct 2024 to Nov 2024

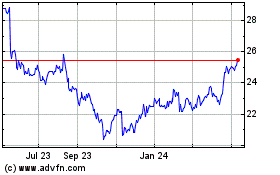

Flowers Foods (NYSE:FLO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2023 to Nov 2024