By Brody Mullins and Jack Nicas

Google operates a little-known program to harness the brain

power of university researchers to help sway opinion and public

policy, cultivating financial relationships with professors at

campuses from Harvard University to the University of California,

Berkeley.

Over the past decade, Google has helped finance hundreds of

research papers to defend against regulatory challenges of its

market dominance, paying stipends of $5,000 to $400,000, The Wall

Street Journal found.

Some researchers share their papers before publication and let

Google give suggestions, according to thousands of pages of emails

obtained by the Journal in public-records requests of more than a

dozen university professors. The professors don't always reveal

Google's backing in their research, and few disclosed the financial

ties in subsequent articles on the same or similar topics, the

Journal found.

University of Illinois law professor Paul Heald pitched an idea

on copyrights he thought would be useful to Google, and he received

$18,830 to fund the work. The paper, published in 2012, didn't

mention his sponsor. "Oh, wow. No, I didn't. That's really bad," he

said in an interview. "That's purely oversight."

The money didn't influence his work, Mr. Heald said, and Google

issued no conditions: "They said, 'If you take this $20,000 and

open up a doughnut shop with it -- we'll never give you any more

money -- but that's fine.'"

In some years, Google officials in Washington compiled wish

lists of academic papers that included working titles, abstracts

and budgets for each proposed paper -- then they searched for

willing authors, according to a former employee and a former Google

lobbyist.

Google promotes the research papers to government officials, and

sometimes pays travel expenses for professors to meet with

congressional aides and administration officials, according to the

former lobbyist. The research has been used, for instance, to

deflect antitrust accusations against Google by the Federal Trade

Commission in 2012, according to a letter Google attorneys sent to

the FTC chairman and viewed by the Journal.

Last month, European regulators issued a $2.71 billion fine

against Google for unfairly favoring its services over rivals' in

its search results. Google has denied the charge.

The funding of favorable campus research to support Google's

Washington, D.C.-based lobbying operation is part of a

behind-the-scenes push in Silicon Valley to influence decision

makers. The operation is an example of how lobbying has escaped the

confines of Washington's regulated environment and is increasingly

difficult to spot.

"Ever since Google was born out of Stanford's Computer Science

department, we've maintained strong relations with universities and

research institutes, and have always valued their independence and

integrity," the company said. "We're happy to support academic

researchers across computer science and policy topics, including

copyright, free expression and surveillance, and to help amplify

voices that support the principles of an open internet."

Google receives nearly $80 billion a year in ad sales drawn

mostly from seven products that each attract more than a billion

global users a month, including Gmail, YouTube and Google maps. Its

search engine handles more than 90% of online searches globally,

according to StatCounter; its Android software will run roughly 1.3

billion of the 1.5 billion smartphones expected to be sold this

year, according to Strategy Analytics.

Through its various enterprises, Google collects information

that reaches deep into daily life -- recording everything from

users' search history to whom they know to where they are --

consumer profiles so rich that not even Google knows their full

potential.

Google has paid professors whose papers, for instance, declared

that the collection of consumer data was a fair exchange for its

free services; that the company didn't use its market dominance to

improperly steer users to Google's commercial sites or its

advertisers; and that it hasn't unfairly quashed competitors.

Several papers argued that Google's search engine should be allowed

to link to books and other intellectual property that authors and

publishers say should be paid for -- a group that includes News

Corp, which owns the Journal. News Corp formally complained to

European regulators about Google's handling of news articles in

search results.

Google has funded roughly 100 academic papers on public-policy

matters since 2009, according to a Journal analysis of data

compiled by the Campaign for Accountability, an advocacy group that

has campaigned against Google and receives funds from Google's

rivals, including Oracle Corp. Most mentioned Google's funding.

Another 100 or so research papers were written by authors with

financing by think tanks or university research centers funded by

Google and other tech firms, according to the data. Most of those

papers didn't disclose the financial support by the companies, the

Campaign for Accountability data show.

Google said in some of its funding letters that it would

"appreciate receiving attribution or acknowledgment of our award in

applicable university publications." There are no professional

standards on such disclosures in the research papers, which are

mostly published in law journals at the universities.

Money spent on the research measures in the low millions of

dollars -- according to the former employee and former lobbyist --

a relatively small expense for the search-and-advertising giant.

Some in academia say professors pay too high a price. Such

corporate funding runs the risk of creating the impression "that

academics are lobbyists rather than scholars," Robin Feldman, of

the University of California Hastings College of the Law, said in a

Harvard University law journal article she co-wrote last year.

Ms. Feldman and other critics of the funding say even disclosing

money received from a company that has benefited from the research

can give the appearance of a conflict of interest and undermine

academic credibility.

"Yeah, the money is good but it does get in the way of objective

academic research," said Daniel Crane, a University of Michigan law

professor. He said he turned down Google's offers to fund his

research that opposed antitrust regulation of internet search

engines. "If I am reading an academic paper, and they disclose an

interest with a party with an interest in the outcome," he said,

"you take [the research] with a grain of salt."

Paying for favorable academic research has long been a tool of

influence by U.S. corporations in food, drug and oil industries.

Scandals involving conflicts of interest in medical research have

spurred many medical schools, scientific researchers and journals

to require disclosure of corporate funding and to prohibit

corporate sponsors from meddling with findings.

The tech industry now includes the world's top five companies by

market value: Apple Inc., Google parent Alphabet Inc., Microsoft

Corp., Amazon.com Inc. and Facebook Inc.

Several of the companies also are active in funding academic

research. Microsoft has paid Harvard business professor Ben

Edelman, the author of papers saying Google abuses its market

dominance. Chip maker Qualcomm Inc. funded papers supporting its

side of a fight against Google over patents. And telecommunication

giants Verizon Communications Inc. and AT&T Inc. have funded

various papers against Google. The companies either declined to

comment or didn't respond to requests for comment.

Google's strategic recruitment of like-minded professors is one

of the tech industry's most sophisticated programs, and includes

funding of conferences and research by trade groups, think tanks

and consulting firms, according to documents and interviews with

academics and lobbyists.

Digital diary

Google collects in-depth data from more than a billion people,

and it uses the information to personalize everything from search

results to YouTube recommendations to online ads. The company's

control of consumer data on such a mass scale has raised antitrust

questions.

Early last year, Daniel Sokol, a University of Florida law

professor, published an academic paper arguing that Google's use of

the data was legal. "There is no cause for concern in this arena,"

he wrote. T he paper also noted that no companies funded the

research.

"If they did," Mr. Sokol said in a footnote of the paper, he and

his co-author "would be sipping Mai Tais with our respective

friends and families on a beach in Hawaii based on the proceeds of

such a sponsorship. We are not."

Mr. Sokol, though, had extensive financial ties to Google,

according to his emails obtained by the Journal. He was a part-time

attorney at the Silicon Valley law firm of Wilson Sonsini Goodrich

& Rosati, which has Google as a client. The 2016 paper's

co-author was also a partner at the law firm, which didn't respond

to requests for comment.

From at least as early as 2013, Mr. Sokol also has coordinated

with Google officials to ensure online symposiums had a pro-Google

bent.

In March 2013, Mr. Sokol helped Paul Shaw, a Google

public-policy official, persuade law professors to write papers for

an online symposium on patents. Mr. Shaw sent Mr. Sokol a list of a

dozen law professors along with specific topics for their papers.

None was paid to participate. Mr. Shaw deferred comment to a

company spokesman.

After the conference, Mr. Sokol submitted a $5,000 invoice to

Google.

In September 2013, Mr. Sokol worked with Rob Mahini, a senior

Google lawyer, to plan an online conference on a separate patent

issue. Mr. Mahini identified professors to participate, and he

asked Mr. Sokol to invite them.

After running into difficulty persuading professors to write

papers for the conference, Mr. Sokol asked Mr. Mahini if Google

could provide "some 'encouragement' to them to participate,"

according to the emails. Mr. Sokol declined to explain what he

meant. Google said it didn't pay professors to participate. Mr.

Mahini didn't respond to requests for comment.

When the symposium ended, a Google assistant emailed Mr. Sokol

about his bill. Mr. Sokol replied: "$5,000, like last time."

Asked for comment, Mr. Sokol wrote in an email: "For the

symposia that I organized, I should have disclosed the sponsorship

for such organization and have now done so. I disclose any

financial support for the articles that I write."

Patent pending

Google and companies that make smartphones backed by its Android

software have for years fought allegations of patent infringements

by Oracle, Apple and Microsoft. The legal dispute has drawn

academic cover on both sides.

Google sought help from Jorge Contreras, a University of Utah

law professor who has also argued for a looser interpretation of

U.S. patent laws.

Since 2013, Mr. Contreras has written numerous papers on

patents. Google helped fund two of those papers, which each

disclosed the financial support. The other papers didn't mention

his relationship with Google.

Google funded a Washington, D.C., symposium in June 2015,

organized by Mr. Contreras, that showcased how Google and other

companies had pledged not to enforce some of their patents,

allowing others to use their technology.

Around that time, Mr. Contreras forwarded his research paper on

the topic to Google policy officials and lawyers: "I would also

welcome your feedback and comments," he wrote in the email.

"It's in really great shape!" a Google lawyer responded. "Would

be good to discuss a couple of things briefly...that are somewhat

related." They set up a phone appointment, according to the email

exchange.

Mr. Contreras said in an interview that he sent the paper as a

courtesy because Google sponsored the conference. He said it was

common among academics to ask for feedback on papers, including

from officials at companies the papers discuss. "They're experts

and in the trenches, and I'm writing about what these people do,"

he said. "So, it's good to get feedback."

A month before the symposium, Google hosted a private daylong

patent-law briefing at the Washington law office of Wilson Sonsini

for several dozen influential public-policy advocates it hoped to

win over. Google paid airfare and hotel expenses for Mr. Contreras

to speak about how the company shares its intellectual

property.

Mr. Contreras said Google doesn't pay professors to change their

positions; it simply funds research that supports the company.

"I don't think there's any dishonesty here," he said, "but they

pick the right people who they know are going to say the right

thing."

Trusted allies

In 2010, Google hired Deven Desai, then a researcher in law and

technology at Princeton University, to find academics to write

research papers helpful to the company.

Over the next two years, Mr. Desai said, he spent more than $2

million of Google's money on conferences and research papers that

paid authors $20,000 to $150,000.

In September 2012, the FTC was nearing a decision on whether to

charge Google with antitrust violations, including its practice of

favoring its shopping and travel services in search results.

Google's law firm, Wilson Sonsini, sent the FTC chairman an 8-page

letter in the company's defense and attached Google-funded research

papers supporting its arguments.

Mr. Desai, now a law professor at Georgia Institute of

Technology after leaving Google in 2012, said part of his job was

to compile a list of "all the major policy academics in

intellectual property so Google lobbyists could know who to follow

and potentially target for papers."

He said Google was careful to say the checks came with no

requirements: "It was a gift. Recipients can do what they

want."

Among the largest were $400,000 stipends that in 2010 went to

several researchers investigating ways to improve users' online

privacy.

Google and other tech companies collect personal information,

including data some users would rather not share. The firms usually

give notice on a privacy policies page about what is collected, and

they often ask for users' consent to keep the information.

Some privacy advocates say the policies are long and confusing,

and few people read them. The advocates seek instead rules limiting

the use of personal data.

Ryan Calo, then a research fellow at Stanford University,

received one of the $400,000 awards in 2010, though he didn't

disclose the funding in one of the two papers he later published on

privacy protection.

That paper suggested finding better ways to alert consumers

about exposing their personal data "before we give in to calls to

abandon notice as a regulatory strategy."

He said in an interview that the Google money was paid to

Stanford, not to him. Nonetheless, he said, he should have

disclosed the financial support in both papers. After publication,

Mr. Calo kept in touch with Google and shared his papers before

publication, emails show.

"I'll be following up with a draft of that paper I mentioned on

how cyberlaw is changing, and look forward to any examples or

thoughts," Mr. Calo wrote on Dec. 20, 2013, to Google officials

about an idea he had on artificial intelligence, robotics and the

law.

Betsy Masiello, a Google official at the time, was copied on the

email and responded: "Also let me know if you have a draft on

surveillance! =)"

Later, after seeing Mr. Calo's research on government

surveillance, Dorothy Chou, a Google spokeswoman at the time, tried

unsuccessfully to arrange for Mr. Calo to discuss his conclusions

on National Public Radio.

"I'm really hoping NPR reaches out so you can get on air to make

those points," she wrote on Jan. 21, 2014. A few days later, she

wrote: "We have another producer asking to chat about government

surveillance, and I wanted to let you know that we pointed her your

way."

Ms. Chou declined to comment, and Ms. Masiello didn't respond to

requests for comment.

Mr. Calo, who is now a professor at the University of

Washington, said it was common practice to discuss research with

companies involved to ensure accuracy: "If you want to have impact

as a scholar, you absolutely need to solicit input from the very

entities you're talking about."

Google officials, he said, "identify work that resonates with a

position they have already, and then they amplify that work."

Write to Brody Mullins at brody.mullins@wsj.com and Jack Nicas

at jack.nicas@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 11, 2017 11:16 ET (15:16 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

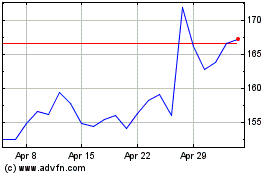

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2025 to Feb 2025

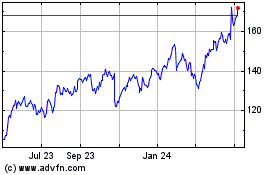

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Feb 2024 to Feb 2025