By Sara Randazzo and Jared S. Hopkins

An Oklahoma judge ordered Johnson & Johnson to pay $572

million for contributing to the state's opioid-addiction crisis, a

verdict that could signal further findings of liability for drug

companies as similar cases wind through courts across the

country.

More than 2,000 cases brought by state and local municipalities

seek to hold drug makers, retail pharmacy chains and distributors

accountable for widespread opioid abuse that began gaining public

attention in the early 2000s. That flood of litigation coincides

with intensifying efforts by the Justice Department to use data to

investigate over-prescription of opioids by doctors.

Oklahoma's case was the first to go to trial and became focused

solely on Johnson & Johnson after two other drugmakers settled

their claims.

In a widely anticipated ruling Monday, Oklahoma state court

judge Thad Balkman said the state proved Johnson & Johnson

launched a misleading marketing campaign to convince the public

that opioids posed little addiction risk and were appropriate to

treat a wide range of chronic pain.

"The increase in opioid addiction and overdose deaths following

the parallel increase in opioid sales in Oklahoma was not a

coincidence," the judge wrote. From 1994 to 2006, prescription

opioid sales increased fourfold, the judge said in the ruling. In

2015, more than 326 million opioid pills were dispensed in the

state, enough for every adult Oklahoman to have 110 pills.

Judge Balkman ordered Johnson & Johnson to pay for just one

year of abatement, not the 20 or more years the state requested. He

said the $572 million should go toward addiction treatment and

overdose prevention services, programs aimed at managing pain

without opioids and other resources.

Johnson & Johnson said it would appeal the judgment and that

the judge's conclusions disregards the company's compliance with

federal and state laws.

"The company here made medicines that are essential for patients

who suffer from debilitating harm," Sabrina Strong, an attorney for

Johnson & Johnson, said after the ruling. "They did it

responsibly."

Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter commended the ruling,

calling it "a major victory for the state of Oklahoma, the nation

and everyone who has lost a loved one because of an opioid

overdose."

Over the course of the seven-week trial, attorneys for Oklahoma

argued that Johnson & Johnson is liable not only for two opioid

drugs it sold -- the fentanyl patch Duragesic and tapentadol pill

Nucynta -- but also because it owned two companies that supplied

the active pharmaceutical ingredients and narcotic raw materials to

other drugmakers for their own opioid painkillers.

The judge said in the ruling that Johnson & Johnson's

misleading marketing included unbranded campaigns jointly developed

with other companies that suggested pain was undertreated and that

higher amounts of opioid prescriptions were the solution. The state

said the company's actions created a "public nuisance" and asked

the judge to award as much as $17 billion to abate the costs of the

crisis.

Analysts followed the Oklahoma trial closely for signs of what

might happen in the broader opioid litigation. Attention will turn

next to Cleveland, where two counties are set to go to trial in

October against an array of drugmakers and distributors. That trial

is serving as a bellwether for hundreds of others brought by cities

and counties that have been consolidated in federal court in Ohio

before U.S. District Judge Dan Polster.

The verdict could put pressure on settlement talks in the rest

of the opioid cases. Judge Polster has pushed the parties to settle

while allowing the October case to head to trial. Complicating

settlement talks is tension between state attorneys general, which

want to maximize recoveries from cases they have filed in state

courts, and the many cities and counties pressing cases in federal

court.

Ashtyn Evans, an analyst at Edward Jones & Co., said damages

were expected to be under $1 billion in the Oklahoma case and

investors were responding favorably to that. "A multibillion dollar

ruling would have been a worst-case scenario," she said.

David Maris, an analyst at Wells Fargo & Co. who covers the

pharmaceutical industry, said he expects companies fighting the

cases consolidated in Ohio will be more motivated to reach a

settlement. The $572 million might be a small amount to a company

of Johnson & Johnson's size, he said, but could be onerous for

smaller companies with larger market shares and more

liabilities.

"There's no manufacturer that's high-fiving their lawyers after

today," Mr. Maris said.

University of Connecticut School of Law professor Alexandra

Lahav cautioned against reading too much into Judge Balkman's

ruling as it pertains to the Ohio litigation, given how public

nuisance laws -- on which the Oklahoma case hinged exclusively --

vary among states.

Traditionally used in property disputes, state attorneys general

are increasingly using such laws in cases against private

industries. A North Dakota judge in March dismissed a case brought

by that state's attorney general against Purdue Pharma, citing the

misapplication of public nuisance laws.

"This is one small data point in a much larger legal picture,"

Ms. Lahav said of Monday's decision.

More than 6,000 Oklahomans have died from opioid abuse since

2000, according to the state. Nationwide, there were nearly 400,000

opioid overdose deaths between 1999 and 2017, federal data

shows.

The judgment surpasses the settlements two other companies

reached in the run-up to trial. OxyContin-maker Purdue Pharma LP

and its owners, the Sackler family, agreed to pay $270 million,

much of it to fund an opioid-addiction research center. Teva

Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. agreed to an $85 million deal.

Johnson & Johnson argued during the trial that its drugs

accounted for a fraction of those taken in Oklahoma and that an

influx of illegal heroin and fentanyl were the real culprits in

overdose deaths.

From 2006 to 2012, Johnson & Johnson's products represented

8% of the market for fentanyl patches and pouches bought by U.S.

pharmacies, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of Drug

Enforcement Administration data. The company represented around

one-quarter of 1% of the market for prescription opioid pills in

that period, the data shows.

The company still makes Duragesic but sold its interests in

Nucynta in 2015 and exited the opioid-ingredients businesses by

2016.

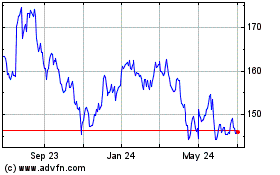

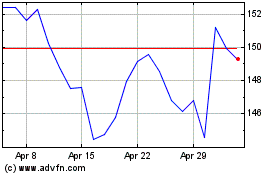

Shares for Johnson & Johnson and other defendant companies

were trading up slightly in after-market trading following the

judgement before losing some of their gains.

Brad Beckworth, a Texas attorney hired to represent the Oklahoma

attorney general's office in the two-year-old case, said the

verdict shows that the opioid crisis is about more than Purdue,

which has drawn the most attention for its role in marketing

OxyContin for wide-ranging pain. "This crisis didn't occur based on

one person or one company," Mr. Beckworth said.

As Johnson & Johnson continues to battle the opioid cases,

it also faces thousands of lawsuits alleging harms from its

signature baby powder, pelvic mesh and hip devices as well as a

handful of pharmaceutical products.

--Joseph Walker contributed to this article.

Write to Sara Randazzo at sara.randazzo@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 26, 2019 19:20 ET (23:20 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

Johnson and Johnson (NYSE:JNJ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2025 to Feb 2025

Johnson and Johnson (NYSE:JNJ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Feb 2024 to Feb 2025