Texas Showdown Flares Up Over Natural-Gas Waste

July 17 2019 - 7:29AM

Dow Jones News

By Rebecca Elliott

A pipeline company is challenging Texas' practice of allowing

drillers to set unwanted natural gas on fire, in a case that could

test state limits for how much of the fuel can legally go to

waste.

As shale companies turned America into the world's top oil

producer, they unlocked massive quantities of natural gas as a

byproduct and Texas has allowed them to freely burn off vast

volumes as area pipelines fill up. The process is known as

flaring.

Now, shale producer Exco Resources Inc. is seeking to flare

nearly all of the gas produced by a group of South Texas wells,

even though its operations are already connected to a network of

pipelines. Williams Cos., the operator of the pipelines, is

challenging the request, in what is believed to be the first such

dispute on record.

Williams attorney John Hays Jr. told commissioners in a hearing

last month that granting Exco's request would open the door to

wasting gas any time doing so is more profitable than transporting

it.

The Texas Railroad Commission has received more than 27,000

requests for flaring permits in the past seven years and has not

denied any of them, records show.

"It just doesn't feel right, quite frankly, to have a standard

that says, any time there's an application, you get an exception,"

Mr. Hays said. "Then why have the statute in the first place?"

Exco has said that rejecting the company's permit application

could force a shutdown of the wells. Attorney David Nelson argued

at the hearing that doing so potentially would reduce long-term oil

production. The company recently emerged from bankruptcy. It

declined to provide additional comment.

The case underscores the tensions surfacing in Texas as the

state grapples with booming oil production and its side effects. It

also exposes a growing rift between frackers and pipeline companies

as the natural-gas glut is set to worsen.

Natural-gas pipeline construction in Texas, home to America's

hottest oil field, the Permian Basin, has lagged far behind

production growth, in part because producers have been reluctant to

commit to long-term contracts. The state's gas output is expected

to increase about 30% over the next five years, according to

consulting firm RBN Energy.

In the region's two largest oil basins, the Permian Basin and

Eagle Ford, operators flared or vented -- where gas is released

without being burned -- into the atmosphere an average of about 740

million cubic feet of gas a day during the first quarter, according

to public data compiled by energy analytics firm Rystad Energy.

That gas would be worth about $1.8 million a day at current prices

and produced greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to that of nearly

five million cars driving for a day, according to estimates from

the World Bank and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Case examiners for the Railroad Commission recommended that

Exco's permit be approved, but the agency's elected commissioners

delayed their vote last month. They are expected to revisit the

matter as soon as August.

Railroad Commission Chairman Wayne Christian declined to

comment. Williams Cos. declined to provide additional comment

pending the Railroad Commission's ruling.

Regulators' decision will have consequences, regardless of which

way it goes. Restricting flaring could cause drillers to curtail

oil production and give pipeline companies additional leverage to

secure contracts and build new infrastructure. Granting flaring

permits in cases such as Exco's could make pipeline companies less

willing to risk building new conduits.

"If they're not willing to limit flaring in this case, then

there's really no regulatory limit on flaring in Texas," said Gary

Kruse, research director for analytics firm LawIQ.

Exco and Williams are fighting over how much the producer should

pay to access the pipeline network.

If the price is too high, Exco says, then it is cheaper to flare

gas than pay for transportation. Although the case involves wells

in South Texas, the conditions mirror those for many operators in

the Permian Basin, the center of Texas' boom.

"The question is: How much onus or economic burden should be put

on a producer to force them to capture and connect that gas?" said

Robert W. Baird & Co. analyst Ethan Bellamy. "Where is the

tipping point?"

Write to Rebecca Elliott at rebecca.elliott@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 17, 2019 07:14 ET (11:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

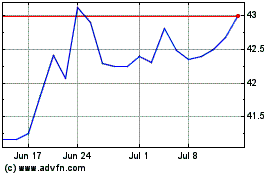

Williams Companies (NYSE:WMB)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

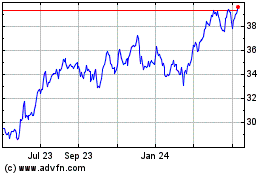

Williams Companies (NYSE:WMB)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024