By Andy Pasztor and Andrew Tangel

Boeing Co.'s engineering failures didn't begin or end with the

737 MAX. Its once-dominant space program, which helped put

Americans on the moon five decades ago, has also struggled.

The company's biggest space initiatives have been dogged by

faulty designs, software errors and chronic cost overruns. It has

lost out on recent contracts with the National Aeronautics and

Space Administration to return science experiments and astronauts

to the moon, amid low rankings on price and technical merit. Boeing

needs revenues from its defense and space arm, which makes

everything from military jets to satellites, as a safety net as it

navigates through the MAX crisis and slowed demand for new

commercial jets in the pandemic.

Its space ambitions will soon face a major test with another

attempt to launch a capsule called the Starliner. In the first

launch, just over a year ago without astronauts on board, a

software error sent the Starliner into the wrong orbit, and then

another threatened a catastrophic end to the mission. A successful

launch, which could come as soon as March, would help restore the

company's reputation for reliability and engineering prowess.

The problems pose a serious challenge for Chief Executive David

Calhoun one year into his tenure as he charts a new course in the

face of uncertainties wrought by the pandemic.

After making record profit of $10.5 billion in 2018, Boeing has

since lost nearly half that amount as of Sept. 30, largely due to a

sharp drop in commercial aircraft deliveries and MAX-related

charges. Defense and space revenue of $19.5 billion in the first

nine months of last year eclipsed its commercial unit's $11.4

billion in sales. Jefferies analysts estimate Boeing brought in

more than $6 billion in space revenue for all of last year.

While the MAX has resumed flying passengers again after a nearly

two-year grounding, quality lapses with popular 787 Dreamliners

have stalled deliveries as Boeing workers fix production defects of

newly finished jetliners. With travel demand still weak, Boeing is

likely to remain heavily dependent in coming years on its defense

and space business.

Boeing declined to make any executives available for interviews.

Mr. Calhoun said in a written statement that the company was "proud

of all the products and services our engineers have developed and

delivered to our commercial and military customers over these last

difficult years, and of the meaningful progress we are making in

safety, transparency and quality."

On the Starliner capsule and MAX alike, software and hardware

systems weren't working properly together due to inadequate

testing, insufficient resources or a combination of the two.

Engineers working on different parts of the same program failed to

coordinate with each other or to properly integrate software and

hardware systems -- and senior managers failed to resolve the

disconnects, according to government reviews and people familiar

with the matter.

Boeing's defense operation has seen similar missteps. The

division has had long-running problems delivering an

aerial-refueling tanker that remains years behind schedule and

billions over budget. Air Force brass ultimately took charge of

designing fixes last year.

The stumbles coincided with what former and current executives,

including Mr. Calhoun, have flagged as another problem: excessive

focus on financial performance, a long-term trend Boeing is trying

to reverse by empowering its engineers.

Senior Pentagon and NASA officials have privately raised

concerns about the range of Boeing's travails, according to several

participants in those conversations. They have questioned Boeing's

ability to deliver on promises about the performance and

reliability of its products.

An Air Force spokesman said the service is "committed to working

with Boeing to field critical capabilities for the warfighter."

NASA officials have said the agency is looking forward to Boeing's

coming uncrewed test and later company missions carrying

astronauts.

Mr. Calhoun, who took over as CEO in January 2020 after spending

a decade on Boeing's board, has pledged to get the company's

troubled programs back on track and to focus more on improving

technical excellence and engineering decision-making.

The company has revamped its internal safety-reporting

procedures and the board's monitoring of overall safety issues --

all aimed at easing schedule and cost pressures on engineers and

giving senior leaders greater oversight of emerging problems. In

November, Boeing hired an engineer who previously worked at Elon

Musk's Space Exploration Technologies Corp., or SpaceX, to be its

first high-ranking executive overseeing software design across the

company. On Wednesday, the company named a longtime senior engineer

as its first chief aerospace safety officer.

There are early signs Boeing's troubled Air Force tanker

program, initially slated to cost $4.9 billion but later viewed as

an albatross by senior Pentagon leaders, is getting on track. Under

a deal with Boeing struck last year, the Pentagon wound up taking

over the primary design of a revamped visual system essential for

allowing aircraft to safely link up with the tankers. Boeing's

previous design adjustments proved ineffective, according to the

Air Force, often preventing the tanker from performing its primary

function.

In exchange for ceding control over the technical details,

Boeing got nearly $900 million in withheld payments when it was

bleeding cash. In return, it must foot the bill for major design

changes, which some people familiar with the matter estimate could

add up to at least $3 billion more in costs for Boeing, though a

person close to the company disputed that the costs would reach

that high.

Air Force procurement chief Will Roper said the Pentagon is

happy with the tanker's new direction, and described it as the

result of an "engineering-first" approach under Mr. Calhoun. Mr.

Roper said Boeing's shift marked a "complete turnaround on this

program."

Since the height of the Cold War, Boeing's name has been

synonymous with dependable jetliners, top-notch military aircraft

and ambitious U.S. space endeavors -- starting with rockets and

lunar rovers the company created for Apollo astronauts in the 1960s

and continuing through its ongoing management of the International

Space Station.

Some former Boeing engineers and government officials trace the

start of Boeing's woes to its 1997 merger with struggling rival

McDonnell Douglas, which they blame for infusing the new entity's

culture with greater focus on financial management. While veteran

engineers have said they never lost sight of safety, some say

reorganizations and turnover hampered communication and

accountability.

Rep. Peter DeFazio (D., Ore.), who as chairman of the House

Transportation Committee investigated the MAX tragedies, blamed

Boeing's failure to add initial safeguards to the jet on the

company's focus on money and sticking to a development schedule.

"That is what ultimately drove Boeing to this tragedy, which is the

press for getting this plane out, to compete with Airbus, and they

were of course driven by Wall Street," Mr. DeFazio said in

September.

Boeing has said its engineers didn't rush what it has described

as the MAX's methodical development and didn't take shortcuts at

the expense of safety. The company has said it was trying to learn

from its mistakes to prevent such crashes from happening again.

Boeing reached a $2.5 billion settlement this month with the

Justice Department on a criminal charge that two company pilots had

deceived regulators about design slip-ups and flight-control

hazards. In court documents, prosecutors said the wrongdoing

financially benefited Boeing but wasn't widespread throughout the

company.

In Boeing's defense and space businesses, an increased reliance

on fixed-price government contracts has squeezed profit margins

because the company typically had to pay the bill for mistakes,

further heightening cost and schedule pressures. Meanwhile,

Boeing's large overhead on top of its multilayered bureaucracy has

made it difficult to compete with more nimble rivals such as

SpaceX.

The launch of the uncrewed Starliner spacecraft from the Kennedy

Space Center in December 2019 was supposed to be a decisive win for

Boeing. The company's leaders planned for directors and other VIPs

to enjoy space-themed gift bags and cheering from a grandstand

during a party after the early-morning liftoff.

Within minutes of the launch, NASA's controllers knew the flight

was going wrong. A software error stranded the spacecraft in the

wrong orbit. Hours later, ground controllers had difficulty

maintaining communication with the vehicle, and later scrambled to

fix another major software mistake.

The Starliner, which never made it to the International Space

Station as planned, eventually returned and landed safely.

NASA and Boeing experts quickly determined the capsule's

thrusters had failed to start at the right time and ended up

depleting their fuel supply, due to faulty software testing,

according to industry and government officials. NASA's leadership,

concerned Boeing had a broader cultural problem in light of the MAX

crisis, ordered a sweeping outside review, resulting in dozens of

recommendations. Many advocated greater attention to plugging gaps

in getting software and hardware to work together properly.

Two fundamental software problems emerged on the Starliner. One

involved a timer on the capsule that hadn't been properly

synchronized with the rocket's internal clock. Boeing didn't

perform a test to verify various software systems were properly

coordinated, which people familiar with the matter estimated would

have caught the error, at a cost of about $1 million.

A separate major mistake involved software controlling thrusters

that help to angle the craft properly to avoid damaging the heat

shield that protects the capsule, and any astronauts inside, during

re-entry. Engineers detected and were able to correct that software

glitch from the ground in time to ensure that what would be the

crew's portion of the capsule safely separated from the rest of the

spacecraft before re-entry.

After the botched mission, Boeing's board -- already frustrated

by the MAX crisis -- ousted then-CEO Dennis Muilenburg and replaced

him with Mr. Calhoun. Mr. Muilenburg had once boasted that Boeing

would be first to put humans on Mars. The company booked a $410

million charge to account for the Starliner launch's redo.

Current and former government and industry officials blame the

spotty testing on cost-cutting and inadequate staff. Boeing was

years late delivering the Starliner under a fixed-price contract

that created incentives for managers to keep a lid on testing and

personnel costs. In addition, the company was vying with SpaceX to

get the first astronauts into orbit on a commercially owned and

operated capsule. Mr. Musk's team handily won that race with

launches in May and November. Another closely held competitor, run

by Amazon.com Inc.'s founder Jeff Bezos, is also taking aim at

Boeing's legacy of space leadership.

A NASA spokesman said "deadline pressures and cost cutting were

not identified" by a joint NASA-Boeing review team as causes of the

Starliner's problems.

Patricia Sanders, chairwoman of NASA's independent

safety-advisory committee, said the signs point to basic lapses in

Boeing's engineering discipline. "It's possible that there was some

complacency that set in," she said, adding that Boeing leaders now

seem to realize they have to change course. "There is a sense that

Boeing overall has woken up."

Boeing, under pressure from government officials, has added

software engineers to the Starliner team, industry officials said.

A newly appointed program manager, John Vollmer, is known for his

ability to execute on difficult programs, according to people

familiar with the matter, and is prodding Starliner engineers to

more thoroughly test software and address problems identified by

the flurry of post-failure reviews.

A Boeing spokesman said the company is poised to begin

full-mission simulation testing as soon as next month after making

software changes recommended by an independent review ordered by

NASA.

Kathy Lueders, NASA's head of human space exploration, has

singled out the agency's overreliance on Boeing's traditional

engineering expertise as the crux of the Starliner's failures.

Rather than reflexively trusting Boeing's technical judgment in

most matters -- as NASA had long done -- "we do need to change our

assumptions as to how we are working together" to ensure Boeing

avoids mistakes, she told reporters in July. The upshot was tighter

restrictions on Boeing's engineering decisions.

NASA has ramped up its own staffing and oversight of Boeing,

acknowledging it probably paid too much attention to keeping tabs

on Mr. Musk's company, until recent years viewed by career agency

officials as an outsider and upstart.

In addition, government watchdogs have criticized Boeing for

persistently missing deadlines and busting budgets as the prime

contractor for the nation's premier deep-space rocket, the mammoth

Space Launch System. Every major component of the heavy-lift

booster has experienced technical challenges and performance

issues, according to a March 2020 report from NASA's inspector

general, resulting in at least $2 billion in recent cost increases.

Additional delays could add another $8 billion.

After nearly a decade of development, it still isn't slated to

fly until November at the earliest. A long-awaited test intended to

fire up all four main engines for the first time is scheduled for

Saturday.

As its engineers work to vet the Starliner's software, the

Boeing spokesman said, the company will perform a full end-to-end

test of the capsule's mission, from prelaunch to landing. For the

next blastoff, people familiar with the matter said, Boeing isn't

planning to hold a flashy party.

Write to Andy Pasztor at andy.pasztor@wsj.com and Andrew Tangel

at Andrew.Tangel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 16, 2021 00:14 ET (05:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

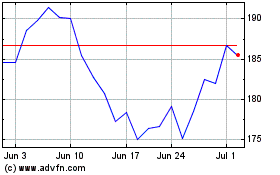

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2025 to Feb 2025

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Feb 2024 to Feb 2025