Joshua Robinson and Andrew Beaton

In the year when everyone went online to play chess online, and

even went online to watch a TV show about chess, players developed

a nasty new habit. They started cheating at chess online.

As newbies and grandmasters alike flocked to platforms like

Chess.com and Lichess in 2020, administrators noticed a surge in

suspicious activity unlike anything they had ever seen. So they

turned to a group of nerds with expertise so obscure that there are

only a handful of them on the planet: the chess narcs.

They are international masters, legal experts, and computer

scientists -- sometimes all three. Their job is to root out

patterns that reveal the player across your virtual board might be

reaching for outside assistance. They are the reason chess has been

able to make the once unthinkable leap from an over-the-board game

with waning popularity to wildly popular esport in a manner of

months.

"It's a constant fight," said Emil Sutovsky, the director

general of FIDE, the chess's world governing body. Without the

chess police, "it would be impossible to host any serious

events."

The moment countries across the world began locking down because

of the pandemic, online chess exploded. And while the world's top

players had to flee a tournament in Siberia back in March, the most

popular chess websites suddenly had to grapple with regulating

online contests in which anyone with a smartphone can beat Garry

Kasparov.

The chess narcs did more than just ensure online games were

fair. They made sure that chess could make the biggest transition

in its 1,000-year history. They beefed up complex algorithms to

detect suspicious moves. They installed intricate video monitoring

systems in players' homes. They reviewed literally hundreds of

millions of games -- and caught tens of thousands of chess cheats,

including grandmasters.

In November alone, Chess.com closed 18,511 accounts for

violating the site's fair play rules. That's thousands more than

any month in the company's history -- and it happened to come in

the same month that a Netflix show about chess, The Queen's Gambit,

became the most popular streaming show in the U.S.

The data showed something curious. More people were playing

chess. Yet the fair play violations were surging even faster than

the number of overall games. "Which makes us think that there has

been an uptick in the rate of cheating," said Gerard Le-Marechal,

head of cheat detection for chess.com.

"What happened with the computer programs becoming better than

humans and chess not adapting definitely stunted the potential of

chess online for at least a decade," said Hikaru Nakamura, the

world's top-rated blitz chess player.

That this is even an issue in chess today is a testament to the

progress chess engines have made over the past 30 years. Powerful

programs that were once deployed only for high-level exhibitions of

man vs. machine are now accessible to any glorified checkers player

with Wi-Fi. Analysis that peers 18 moves into the future and knocks

off grandmasters is only a click away.

That's also why chess insisted on staging in-person events until

the pandemic. Using technology to cheat in over-the-board

tournaments usually required a small-scale conspiracy. Famous cases

have involved hidden devices, audience members with secret phones,

and even spectators communicating moves based on where they are

standing.

But on the internet, no one knows you're a fraud. "That's where

the algorithm and secret sauce does its heavy lifting," Danny

Rensch, chess.com's chief chess officer, said.

Chess.com has a team of two dozen people constantly tinkering

with complex codes that review more than 5 million games a day on

the platform to root out this behavior from middling pawn pushers

to the game's elite. Its most basic systems search for how often a

player matches the moves from popular computer engines. Its

advanced ones are so intricate that they essentially decode a

player's chess DNA by understanding their abilities and tendencies

so well that it can flag when moves stray too far afield.

Rensch concedes there may still be players cheating and getting

away with it. They only close an account when they have

irrefutable, statistical proof they are right. The systems were

proven when they flagged several of the world's top-100 players for

cheating -- and those players subsequently confessed.

"There's no way seven years ago I would've closed a player in

the top 100," Rensch said.

Those systems have now enabled major tournaments run by the

likes of FIDE and the U.S. Chess Federation. A handful of players

have been barred from FIDE's top online competitions during the

pandemic because they had been flagged by chess.com's mechanisms.

The algorithms are buttressed by requirements that players turn on

a minimum of two cameras -- one showing their face, another from

behind them -- and share their screens while playing to prevent

them from consulting other sources.

"We set the bar quite high," said Sutovsky, of FIDE. "If you

play just well, you would not be under suspicion. If you play

exceptionally well and there is a 1-in-50,000 chance of that, then

we investigate."

There are now online tournaments featuring the likes of world

champion Magnus Carlsen with hundreds of thousands of dollars on

the line enabled by this fast-growing cheat detection

infrastructure. But the modern genesis of this cottage industry

dates back more than a decade to a scandal known simply as

Toiletgate.

The controversy erupted at the 2006 world championships when

Vladimir Kramnik, of Russia, was accused of taking a suspicious

number of bathroom trips. Though no wrongdoing was proved and

Kramnik went on to win the title, the incident caught the attention

of a computer scientist -- and an international chess master -- in

upstate New York. His name is Ken Regan and he became obsessed with

flushing out cheaters.

"I saw the game I love potentially cracking apart," said Regan,

an associate professor of Computer Science and Engineering at the

University at Buffalo. "I'm not a vigilante by any means. I don't

go out looking for trouble."

Trouble comes looking for him. Before the pandemic, Regan would

personally investigate a handful of tournaments a year. Now, he

says, the volume of online play he's asked to sift through is "more

than I can bear." In 2020, Regan alone has processed more than

80,000 performances.

The underlying principle is based on evaluating a player's

chances of finding the best possible move over the course of a

game. Sometimes that move will be obvious. But in key situations,

finding the optimal move can require a level of forethought that is

beyond the capacity of most humans working with a time constraint.

Finding those marginally better moves over and over is what raises

the alarm.

"If there are four moves and one of them is slightly better than

the others and you match the computer 10 times in a row under those

circumstances," Regan said. "That's million to one face-value

odds."

Among grandmasters, those shady patterns are harder to spot. The

expectation is higher that they will find the cleverest moves and

they also tend to be more careful. Instead of using chess engines

to blow defenses apart, they cheat for incremental gain, making

perfect midgame moves that nudge their chances of winning higher.

In other words, when the world's best players cheat, they are not

throwing wild 80-yard touchdown passes -- they are stealing a

couple of yards on second-and-3.

Sutovsky called this "smart cheating." In one infamous September

incident, Armenian grandmaster Tigran Petrosian -- not to be

confused with Armenia's greatest ever player, also named Tigran

Petrosian, who was a world champion in the 1960s -- was caught

cheating in the semifinals and finals of an event. (He denies any

wrongdoing.) Petrosian received a lifetime ban from chess.com and

the PRO Chess League, a prestigious team competition.

Getting nabbed by the chess cops is bad. Getting sentenced by

the chess judges is worse.

"If you get caught cheating," Nakamura said, "your whole career

is over."

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 08, 2020 10:13 ET (15:13 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

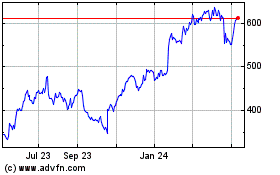

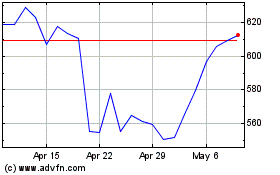

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2024 to Dec 2024

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Dec 2023 to Dec 2024