By Chris Kornelis

Since losing his vision at age 13, Erik Weihenmayer has summited

Mount Everest, white-water rafted and climbed frozen waterfalls.

But making soup in his kitchen presented a unique challenge. On a

frozen waterfall he could tap his ax against the ice to get a feel

for its density, but in the kitchen, he had no way to differentiate

between cans of tomato and chicken noodle.

Mr. Weihenmayer, 49 years old, found a solution in Microsoft

Corp.'s Seeing AI, a free app for the visually impaired. Among

other things, the app can recognize faces, identify money, read

handwriting and scan bar codes to differentiate between cans of

soup.

"It is a game-changer," says Nathan Brannon, a blind 54-year-old

Seattle resident who tests software for accessibility.

Seeing AI is just one of the artificial-intelligence-powered

products that are helping blind and vision-impaired people live

more independently. Improvements in voice recognition and computer

vision, along with machine learning, have led to specialized

products such as Seeing AI, as well as mainstream devices like the

Amazon Echo, that are allowing the visually impaired to tackle

everyday tasks sighted people take for granted. Advocates for the

blind say these technologies have the potential to fundamentally

change the mobility, employment and lifestyle of the blind and

vision-impaired.

Microsoft says it has no plans to monetize the app, which

launched in 2017, calling it part of the company's efforts to

empower all people, including those with disabilities.

Visual interpreter

Of course, many of the voice-activated devices that have become

powerful aids for the blind, such as Amazon's Echo and Google Home,

weren't specifically designed for them, or with philanthropy in

mind.

Mr. Weihenmayer, for example, uses Comcast's voice remote to

find TV shows, Apple's Siri to send texts and Amazon's Alexa to cue

up his favorite music.

Mike May and his wife, both of whom are blind, have about a

dozen Alexa-connected devices in their home that do everything from

turn off the lights to tell them when a load in the washing machine

will be done. "It's become so much a part of my life that I almost

don't even think about it anymore," says Mr. May, who works at

Wichita, Kan.-based Envision, a provider of services for the blind

and visually impaired.

Both Mr. May and Mr. Weihenmayer also use a product called Aira,

which uses glasses with a camera, sensors and network connectivity

to connect the visually impaired to human agents, who act as visual

interpreters. The reps can describe users' surroundings and assist

them with tasks such as online searches.

"They have it done in two minutes," Mr. May says of online

searches. "It takes me 10 times as long and I'm fairly

proficient."

Mr. May once used Aira, made by Aira Tech Corp., to get a

different look at Seattle's Pike Place Market, which he usually

navigates with the help of a guide dog. The Aira rep described the

scene in detail, Mr. May says, right down to the interesting

tattoos adorning a checkout person. The technology costs between

$89 (for 100 minutes) and $329 (unlimited minutes) a month, though

some hotels, airports and retailers offer free access to their

guests through a program called Aira Access.

"I think this technology gives people the confidence to go out

and explore unknown areas where you just might be a little bit

hesitant to go out as a blind person," says Mr. Weihenmayer, a

co-founder of No Barriers, a nonprofit that supports and advocates

for people with disabilities.

Aira uses artificial intelligence for some tasks already, such

as identifying pill bottles, says Suman Kanuganti, founder and

chief executive of Aira Tech. But he expects AI eventually to take

over more of the work the human reps are now doing, such as

navigating.

Aira has raised roughly $15 million from investors. Mr.

Kanuganti says its user base is in the low thousands and it has

provided more than one million minutes of services in more than

100,000 sessions.

One major hurdle to bringing specialized products for the blind

to market is the size and disposable income of the target audience.

The World Health Organization estimates that of the 253 million

people world-wide who live with vision impairment, 36 million are

blind. The Census Bureau estimates that more than seven million

Americans are visually impaired. Many of them are unemployed or

underemployed.

"You cannot build a business around only blind people," says Ziv

Aviram, co-founder and CEO of Israel-based OrCam, the maker of the

MyEye 2.0 device, which is targeted at people with low vision but

can be used by the blind, as well. "You can do philanthropy, but

not business."

MyEye 2.0 mounts onto the side of glasses and can recognize

money, faces and surroundings. When users point their fingers at

signs or menus, MyEye can read them. The device, which costs around

$4,500, in some cases is covered by the Department of Veterans

Affairs, as well as some workforce associations, OrCam says.

Robert Beckman, the CEO of Middleton, Wis.-based Wicab Inc.,

says his company's $8,000 BrainPort V100 device is out of reach for

most blind people. The device consists of a camera mounted to a

pair of sunglasses that relays images to a plate of sensors that

users hold in their mouths. The sensors electronically sketch an

image of what the user is looking at onto the user's tongue. So

far, Mr. Beckman says he has been unable to get Medicare to cover

the device, and insurance companies have covered it only on rare

occasions. As a result, the company has sold fewer than 100 units,

he says.

Built-in accessibility

As much as blind people need specialized technology, building

accessibility into mainstream products may be an even bigger need,

say advocates such as Mark Riccobono, president of the National

Federation of the Blind.

He points to the iPhone, which had accessibility built into it

from the beginning.

"I can go down to the Apple store and pay the same price and

triple-click the home button and I have VoiceOver," says Mr.

Riccobono, referring to a feature where the phone will describe

aloud what is happening on the screen. "That's built in, it's

great, it doesn't cost a penny extra."

One coming mainstream technology that could be life-changing for

the blind is the driverless car.

"Transportation can be a very large barrier in the lives of

blind people, " impeding everything from employment to education,

says Eric Bridges, executive director of the American Council of

the Blind. "Having the ability to have one of these vehicles come

and take you where you want to go, when you want to go, and not be

constrained by the paratransit system or the fixed-route system,"

promises a greater level of independence and freedom, he says.

In a white paper last year, the Ruderman Family Foundation,

which advocates for the inclusion of people with disabilities in

society, claimed self-driving vehicles "would enable new employment

opportunities for approximately two million individuals with

disabilities, and save $19 billion annually in health-care

expenditures from missed medical appointments."

Mr. Bridges and Mr. Riccobono are pushing manufacturers to keep

the blind in mind when designing driverless cars. Specifically,

they want the car's controls and console to be accessible to those

who can't see, which "probably means more than just having it

talk," says Mr. Riccobono.

Waymo -- Alphabet Inc.'s self-driving-car unit, which plans to

launch a self-driving-car service this year -- says it is putting

audio tools and Braille labels inside its cars to allow visually

impaired riders to do everything from pull the car over to call an

operator. "We continue to learn about the unique needs of different

riders, and what we learn will inform new features that will make

the experience accessible to people who have historically had to

rely on others to get around," Waymo said in its 2018 Safety

Report.

Anna Catherine Walker, a 17-year-old visually impaired

high-school junior in Mechanicsburg, Pa., says she, for one, can't

wait. "I live out in the middle of nowhere," she says. "I want to

be able to leave without having to drag someone along with me."

Baking accessibility into the driverless car and other

technology products could have ramifications beyond the

vision-impaired community. Anirudh Koul, a senior data scientist at

Microsoft who helped launch Seeing AI, says history is rife with

examples of products and technologies that were developed for or

inspired by the needs of the blind that resulted in mainstream

products -- such as audiobooks and scanners. He has already seen

mainstream crossover with Seeing AI, such as sighted customers in

Asia using the app to learn the English word for the object in

front of them, and technicians using the app to read hard-to-access

text on the back of servers.

Mr. Kornelis is a writer in Seattle. Email him at

reports@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 28, 2018 22:21 ET (02:21 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

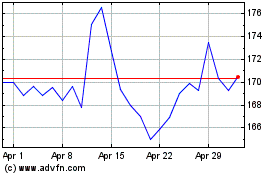

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

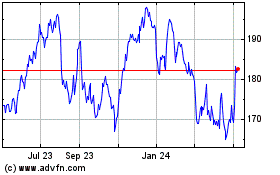

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024