By Jon Emont

DHAKA, Bangladesh -- Five years after a factory collapse killed

1,100 workers in Bangladesh's worst industrial disaster,

organizations representing Western brands say that authorities in

the country aren't ready to go it alone to ensure safety standards

are up to scratch.

Shortly after the Rana Plaza tragedy, North American and

European retailers established two parallel organizations to

inspect Bangladeshi factories and mandate safety repairs. Both

groups initially planned to phase out in 2018.

Instead, the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Safety, backed by

European brands such as Hennes & Mauritz AB and Zara owner

Inditex SA has announced plans to extend its efforts for up to

three more years.

The Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, which includes North

American companies such as Walmart Inc. and Gap Inc., will wind

down its operations this year. It plans to establish a smaller

safety monitoring organization to ensure the factories the

Alliance's brands source from that are already up to code continue

to maintain rigorous inspections.

"The national safety regulatory body that's supposed to be doing

the work that we've been doing over the last five years is nowhere

near prepared," said Rob Wayss, executive director of the

Accord.

Bangladesh's government tried to upgrade its monitoring and

inspection regime for factories after the disaster, but progress

has been plodding, according to data compiled by the International

Labor Organization from Bangladesh government sources.

Of 754 garment factories that are part of the Bangladeshi

government's safety program, just 109 have resolved more than half

of the safety issues identified, which include structural, fire,

and electrical safety -- a significantly slower rate than factories

covered by the Accord and Alliance. The Accord covers around 1,600

factories and the Alliance 666, although there is significant

overlap.

Md. Shamsuzzaman Bhuiyan, Inspector General for the Department

of Inspection for Factories and Establishments, said his unit has

the resources to take over the inspections for factories currently

being monitored by the Accord and Alliance. He said he didn't agree

with the Accord's views on the matter. "We believe that DIFE is

capable of conducting the inspections. A good number of engineers

have been recruited," he said.

Bangladeshi authorities have "got their hands pretty full," said

Jennifer Bair, associate professor of sociology at the University

of Virginia, who has researched the Bangladesh apparel industry.

"It's going to be a really tall order to both complete the

remediation of the existing factories and also assume

responsibilities that are currently under the jurisdiction of the

Accord and Alliance."

Since the garment industry took off in Bangladesh in the 1980s,

it has been plagued by industrial disasters, including the Tazreen

fire of 2012, which killed more than 100 people after managers

prevented workers from leaving their stations after a fire alarm

sounded.

Industry analysts say garment factories have become less

dangerous since 2013, though the Bangladeshi government doesn't

compile comprehensive statistics on factory injuries and deaths.

Still deadly incidents continue, including a boiler explosion at a

garment factory last year that killed 10 workers and injured dozens

more.

Under the Alliance and Accord, factories that don't invest in

safety improvements are blacklisted from selling to major western

retailers, a move designed to protect the roughly 3 million

Bangladeshis making garments for the brands.

Western retailers have continued these efforts also because

their biggest investors want to ensure that factory improvements

made after the Rana Plaza collapse are maintained to lower the

reputational risk of doing business in Bangladesh.

"You have to make sure that everything you have worked so hard

for doesn't fall flat the moment you leave," said Anna-Sterre

Nette, Senior Advisor Responsible Investment and Governance to MN,

a major Dutch pension fund manager that invests in the apparel

sector.

The Accord and Alliance report that over 80% of factory safety

issues identified in safety inspections, such as inadequate fire

escapes and dangerous electric wiring, have been fixed.

Such efforts have "helped to establish a culture of safety,"

said David Hayer, Senior Vice President of Global Sustainability at

Gap, a member of the Alliance.

Walmart, a founding member of the Alliance said its goal was to

transition to a "locally-run safety monitoring organization" that

will maintain factory safety programs pioneered by the

organization, such as a worker helpline.

The Accord has said it extended its efforts partly because it

needed more time to complete its mandate. While it has successfully

removed lockable and collapsible gates from nearly all factories

that had them, preventing factory owners from locking their workers

in during the workday, more expensive and complex operations are

taking longer. For example, only 39% of Accord factories that had

inadequate fire systems during initial inspections have since

installed fire detection and prevention systems that are fully up

to code.

Bangladesh still needs help when it comes to monitoring safety,

said Sayeeful Islam, the managing Director of Concorde Garments, a

company that sells to a range of western retailers including

Walmart. If the Accord and Alliance were to leave Bangladesh, "I

would be worried for my country."

Write to Jon Emont at jonathan.emont@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 29, 2018 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

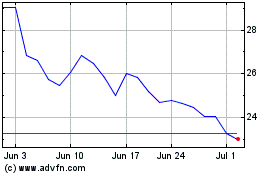

Gap (NYSE:GPS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2024 to May 2024

Gap (NYSE:GPS)

Historical Stock Chart

From May 2023 to May 2024