By Andy Pasztor

U.S. air-safety regulators are set to begin key flight tests of

Boeing Co.'s 737 MAX as early as Monday, amid growing expectations

by industry and government officials that the planes are likely to

return to service around the end of the year.

The airborne checks, slated to be conducted in conjunction with

Boeing and scheduled to last three days, mark a preliminary

validation and long-awaited milestone for Boeing's technical fixes

aimed at getting the MAX fleet back in the air. The planes have

been grounded for 15 months following two accidents that killed 346

people, roiled the airline industry long before the coronavirus

pandemic and dealt the biggest blow to the plane maker's reputation

in its 103-year history.

In an email the Federal Aviation Administration sent to

congressional staffers Sunday, the agency said the effort "will

include an array of flight maneuvers and emergency procedures to

enable the agency to assess" whether a series of software and

hardware changes complies with safety certification standards.

But as expected, the FAA stressed agency officials haven't even

tentatively completed those evaluations yet, while the message laid

out a handful of additional steps anticipated to take at least

several months -- some involving outside experts, foreign

authorities and requests for public comment.

Still, after more than a year of delays, persistent new

engineering challenges and friction between senior FAA officials

and Boeing's management, Sunday's message laid out the clearest

path yet for resurrecting the MAX.

The crashes, which occurred less than five months apart in late

2018 and early 2019, kicked off debates in Congress and throughout

the industry about FAA procedures and safeguards for approving the

safety of new jetliner designs. The deaths also touched off a

federal criminal investigation and prompted substantial changes in

decades-old assumptions about how typical pilots interact with

complex cockpit automation.

A Boeing spokesman said: "We continue to work diligently on

safely returning the MAX to service."

FAA officials have consistently said they wouldn't move toward

authorizing such test flights or taking other actions to recertify

the MAX until all the agency's questions and concerns were answered

satisfactorily. Leading up to test flights, Boeing has conducted

more than 2,000 hours of flights to validate new software.

The world-wide slump in passengers resulting from the Covid-19

pandemic, though, has sharply reduced the airline industry's

appetite for flying the troubled planes, and Boeing has

dramatically scaled back its own production rates from previous

levels.

Before making the decision Friday to schedule test pilots to vet

various software fixes and changes to the jet's flight-control

systems, the FAA formally signed off on a series of Boeing

technical analyses and risk assessments that had taken months.

Within days of the second crash, Boeing launched an effort to

develop initial software revisions to an automated flight-control

system called MCAS, which misfired, overpowered pilot commands and

put both MAX jets into nosedives.

Under prodding from the FAA and international regulators, Boeing

since then has revised several other features of the MAX's

flight-control computers and associated hardware, including

agreeing to relocate certain electrical wiring under the cabin to

avoid hazardous short circuits.

The test flights, once planned for the summer of 2019, continued

to be postponed as FAA and Boeing experts expanded their work to

cover an array of new safety issues and previously unexamined

computer shortcomings.

Even if the flight tests go well, the MAX faces more testing of

the plane's handling by a group of international pilots, further

analyses by pilot-training officials, verification by teams of

outside safety experts and extensive maintenance work before the

jetliners can be deemed ready to fly passengers.

In addition, Canadian and European regulators are pushing for

other software changes that could be phased in over a year or more,

once the planes return to service. Such separate safety tracts,

according to many industry officials, threaten to erode the FAA's

historic stature as the world's dominant air-safety regulator.

"There likely will be multiple changes attempted, many for

nontechnical issues which will consume lots of time," said Ray

Valeika, retired head of maintenance and engineering at Delta Air

Lines Inc.

Over the months leading up to the decision to schedule the

flights, industry and government officials projected that the FAA

was likely to officially lift its order grounding the planes by

early fall.

Airline officials have said they anticipate needing roughly two

months after such a move to prepare aircraft for flight, phase them

into their fleets and arrange for pilots to complete extra training

in ground-based flight simulators expected to be required by the

FAA. With some potentially important exceptions, international

regulators are expected to follow the FAA's lead and clear the

planes to fly within weeks of a final U.S. announcement.

Some 800 MAX planes are grounded, with roughly half of them in

storage under Boeing's control because they were never delivered to

customers.

With thousands of jetliners of various types sitting idle around

the world because of the coronavirus pandemic, industry officials

expect most airlines to move slowly to fit 737 MAX planes into

truncated schedules.

Results of the test flights aren't likely to be released

immediately, and a formal write-up could take weeks, according to

industry and government officials. Later this summer, House and

Senate leaders are expected to engage on provisions in rival bills

intended to overhaul FAA certification of new aircraft designs.

FAA chief Steve Dickson, a former military and airline pilot,

has said that before the agency's decision, he would personally

test the revised software.

To boost passenger confidence in the redone flight controls,

U.S. airline officials previously raised the possibility of

conducting their own demonstration flights of MAX aircraft with

executives and pilot-union leaders on board. The FAA has also

considered strategies to explain the changes to regulators in other

countries to ensure a coordinated return of the fleet.

Earlier this month, Boeing sent airline customers draft training

materials, including more than a handful of revised checklists and

rewritten emergency procedures, to pave the way for returning the

MAX to service. At the time, the plane maker said it had worked

closely with aviation authorities on the draft, noting that

multiple regulators requested different changes to cockpit

procedures.

Andrew Tangel contributed to this article.

Write to Andy Pasztor at andy.pasztor@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 28, 2020 17:56 ET (21:56 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

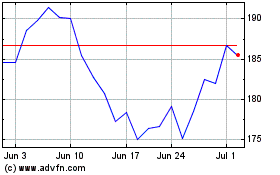

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024