By Andy Pasztor

Boeing Co.'s engineering mistakes and "culture of concealment,"

coupled with insufficient federal safety oversight, led to two

fatal crashes of the plane maker's 737 MAX aircraft, House

investigators said in a report released Friday.

The preliminary findings, issued by Democrats on the House

Transportation Committee, describe in stark terms the engineering

and regulatory lapses revealed in five public hearings over the

past year into the design and certification of the MAX, which was

grounded around the world last March following a second crash of

the passenger jet.

The crashes of the Ethiopian Airlines flight and the Lion Air

flight five months earlier, claimed a total of 346 lives. The

protracted grounding continues as Boeing works on software fixes

and develops pilot-training requirements that will win the approval

of regulators. Boeing halted the aircraft's production in

January.

Friday's report details Boeing's determination at various levels

-- years before the MAX was approved by the Federal Aviation

Administration -- to avoid putting pilots through costly

ground-simulator training. That single-minded goal was evident

across Boeing's engineering, marketing and management ranks,

according to the report, and resulted in various efforts to mislead

or withhold information from FAA officials during the lengthy

certification process.

Both crashes occurred after pilots failed to counteract a new

automated flight-control feature -- details of which they didn't

know -- that misfired to repeatedly and aggressively push down the

nose of their aircraft.

The 13-page congressional report offers new details about what

it described as Boeing's improper conduct related to MAX, including

fresh insight into the period during the plane's development and in

the weeks after the first crash.

In July 2014, three years before the MAX started flying

passengers and two years before the FAA made a decision regarding

the extent of mandatory pilot training, the report says Boeing

issued a press release seemingly predetermining the regulatory

process. The company said pilots already flying earlier 737 models

"will not require a simulator course to transition to the 737 MAX."

According to the report, Boeing made the same pledge to airliner

customers, including Ethiopian Airlines.

During the plane's development, Boeing successfully argued to

remove references to the flight-control system, known as MCAS, from

official manuals. As the House committee revealed earlier, the

company also went to great lengths to keep FAA officials from

scrutinizing and potentially recognizing the hazards of the system,

even referring to it by another name.

The FAA's oversight effort was "grossly insufficient and...the

FAA failed in its duty to identify key safety problems," according

to the report.

The FAA said the agency welcomes the scrutiny and the lessons

from the two crashes would bolster aviation safety.

A Boeing spokesman said, "We have cooperated extensively for the

past year with the committee's investigation; we will review this

preliminary report."

The report offered fresh insight into Boeing's actions after the

first crash in Indonesia. The panel concluded that Boeing continued

to minimize the importance of MCAS -- and persisted in deflecting

the need for additional pilot training -- even in the wake of the

Lion Air crash in October 2018 and stepped-up FAA assessments of

the system's hazards.

Based on hundreds of thousands of pages of internal documents

and other material Boeing turned over to the committee, the report

spells out steps Boeing took to defend itself in the weeks after

the Lion Air crash. At the time, the report indicates, Boeing

maintained that design changes that had made MCAS more powerful

complied with all safety rules and requirements.

Despite the Lion Air crash and the public outcry it created,

Boeing sought to persuade the FAA to downgrade training

requirements on MAX jets in general, according to House

investigators. Their report says the effort by Boeing came in the

face of regulators' warnings that the company's technical

evaluation of the issue was at odds with the views of FAA

experts.

The report reiterates earlier complaints by lawmakers that the

Chicago-based aerospace giant was able to exert undue influence

over the FAA, partly because regulators delegated much of their

oversight responsibilities to Boeing employees authorized to act on

the government's behalf.

It also detailed examples of FAA managers overruling safety

concerns of their own technical experts related to another Boeing

airliner, the Boeing 787.

The Democratic-controlled House committee intends to continue

its probe, but Rep. Peter DeFazio, the Oregon Democrat who chairs

the panel, surprised some industry officials and prompted blowback

from Republican members by opting to release a preliminary report.

Coming days before the anniversary of the Ethiopian Airlines MAX

crash in March 2019, Democrats hope the material will provide

momentum for significant legislative changes tightening FAA

oversight.

Rep. DeFazio sought to avoid a partisan rupture during the

committee hearings. But hours after the report came out, a pair of

senior GOP panel members issued a rebuttal suggesting its

conclusions were premature and potentially biased. The Republican

statement said other reviews of the FAA's approval process for new

aircraft designs haven't concluded the "system is broken or in need

of wholesale dismantlement."

The minority report said that rather than rushing out a report

to meet an artificial timeline, "we need to get this right" and

"fix the problems that need to be fixed to make our fundamentally

safe system even safer."

While the document lays out a pattern of Boeing moves "to

obfuscate information about the operation of the aircraft," it

equally targets the FAA for inadequate safeguards and disjointed

internal communications.

Even following the Lion Air crash, according to House

investigators, the FAA missed red flags that should have alerted it

about the extent of Boeing's previous failure to adequately test

the combined impact of various sensor and other malfunctions that

could result in MCAS activation. Boeing and the FAA quickly agreed

the system's software needed a major redesign, though the report

indicates FAA officials allowed the plane to keep flying despite

multiple prior certification blunders pertaining to the MAX.

Separately, in Boeing's latest reported production lapse, the

FAA on Friday proposed a $19.7 million penalty against the company

for installing unapproved sensors on nearly 800 jetliners,

including 173 of its 737 MAX models.

The alleged missteps, extending from mid-2015 to the spring of

2019, highlight Boeing failures to comply with its own

quality-control rules covering aircraft production. The proposed

civil penalty, at the upper end of what regulators could seek based

on the number of affected aircraft, also reflects increased FAA

scrutiny of Boeing's assembly-line safeguards.

Covering more than 600 earlier 737 models, the enforcement case

stems from alleged Boeing slip-ups in failing to ensure sensors

associated with certain windshield cockpit displays had been

approved by regulators for specific applications. The letter to

Boeing laying out the details, dated Friday, doesn't indicate any

operational safety incidents as a result of the alleged

violations.

A Boeing spokesman said the company has done a thorough internal

review and implemented changes to address the FAA's concerns.

Write to Andy Pasztor at andy.pasztor@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 06, 2020 18:46 ET (23:46 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

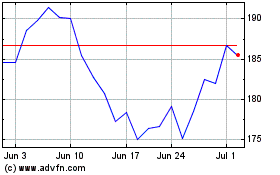

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024