By Krishna Pokharel

KATHMANDU, Nepal -- With all six ventilators at a hospital in

central Nepal already being used by Covid-19 patients on Sunday,

doctors asked the son of Lal Bahadur Thakur to try to find one

somewhere else, as his father gasped for breath.

As India's Covid-19 surge has swept into Nepal, hospitals are

reporting an overwhelming number of severe cases and similar

shortages of beds, oxygen and ventilators. Much like what happened

in India, cases have risen faster here than during any previous

outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, quickly overwhelming a

healthcare system with fewer resources than its much larger

neighbor to the south.

"We have already lost two patients like him today waiting for

ICU beds or ventilator support. We feel utterly helpless," said Dr.

Dipendra Pandey, who was treating Mr. Thakur at the government-run

Trishuli Hospital in Nuwakot district, about 50 miles outside

Kathmandu, the capital city.

Mr. Thakur's 20-year-old son, Chandan Thakur, made a flurry of

calls to hospitals in the nearest cities -- Kathmandu, Chitwan and

Pokhara -- as his father's blood oxygen levels dropped below 60%.

None of them had available beds or ventilators, he said.

On Monday morning, Mr. Thakur, 50, died of acute respiratory

distress syndrome due to Covid-19, despite the hospital's efforts,

Dr. Pandey said.

The Covid-19 wave now battering India and Nepal shows the danger

for many regions of the developing world that remain largely

unvaccinated. Public-health experts and scientists say a highly

infectious coronavirus variant first identified in India appears to

be fueling a precipitous rise in cases in Nepal, and await the

genomic sequencing of more samples to be certain.

In early March, Nepal was reporting around 100 new daily

Covid-19 cases. In recent weeks, new daily cases have shot up to

more than 9,000, the highest since the pandemic began, and about

200 people are dying a day, according to the Ministry of Health and

Population.

The numbers don't likely reflect the full extent of the surge.

The positivity rate for coronavirus testing has been about 45% in

recent days. The high rate is mainly due to the country's limited

testing, said Laxman Aryal, Nepal's health secretary.

Since November, the government has been limiting the

availability of free testing, treatment and quarantine centers to

those most in need, saying the resource-constrained country needed

to save money to buy vaccines. Now the country tests only people

with symptoms and those who have been in immediate contact with

people who have tested positive, said Mr. Aryal.

Despite the efforts to save money for vaccines, by the end of

April the country had fully vaccinated only about 362,000, or 1.2%,

of its 30 million people, an example of how far developing

countries lag behind the U.S. and parts of Europe, where

vaccination campaigns are already setting the stage for economic

recoveries and a steady return to normalcy.

Nepal isn't the only country to see a recent increase in cases,

but the surge here has mirrored the rapid rise in India.

Public-health experts say the surge in India has likely spread

to Nepal through the countries' shared open border. Hundreds of

thousands of Nepali migrant workers, fleeing India's outbreak have

returned home, with little to no screening at border checkpoints.

Nepali Hindus also traveled to India to participate in this

spring's Kumbh Mela festival in northern India -- including the

country's former king and queen, who tested positive soon after

returning.

Preliminary results from a small number of samples suggest

variants circulating in India are now present in Nepal. A lab that

did genomic sequencing of a dozen samples in the Kathmandu Valley

in late April and early May found that 11 of them were versions of

the variant first identified in India, B.1.617, and one was the

variant first identified in the U.K., B.1.1.7, said Dibesh

Karmacharya, executive director of the Center for Molecular

Dynamics Nepal.

Nine of the 12 were of one particular subtype of the variant,

B.1.617.2. "It is the same one creating havoc in India right now,"

said Mr. Karmacharya.

The government has sent a wider pool of samples to the World

Health Organization for genomic sequencing, said Mr. Aryal, the

health secretary.

The country's hospitals meanwhile are seeing more severe cases

of Covid-19, including among younger patients in their 30s and 40s,

which they are guessing is due to mutations in the virus that are

making it more virulent, Nepal doctors and health officials

said.

"The disease has become unpredictable, and we are struggling to

understand it," Dr. Pandey said. "Compared to the first wave, the

patient's condition this time is deteriorating very fast before we

can do much."

The crisis now gripping Nepal is a cautionary tale for other

small developing countries with weak healthcare systems and little

vaccine protection.

"I am afraid that if you don't have a very systematic approach

to this problem, we are going to run again and again with the

second wave and third wave and the fourth wave, and so on," said

Mr. Karmacharya. "And each wave, you are going to have a stronger

variant."

Nepal started its vaccination campaign in January with about 2.3

million doses of vaccine from AstraZeneca PLC. About 1.5 million

people have been left waiting for their second dose. Nepal has

ordered an additional one million doses from the Serum Institute of

India with an 80% advance payment, but those have been held up

because of India's suspension of vaccine exports, said Jageshwor

Gautam, a spokesman for the health ministry.

As of April 2020, Nepal had only 840 ventilators, about 1,600

ICU beds and fewer than 200 hospitals with intensive-care

facilities, according to the health ministry. There were 23,146

medical doctors in the country in 2019, according to the World

Health Organization data, amounting to eight for every 10,000

people, compared with 9.2 in India and 26 in the U.S.

The most immediate concern, though, has been the lack of medical

oxygen. Nepal has the capacity to produce 8,000 to 9,000 oxygen

cylinders a day, but the demand is nearly twice that amount, said

Mr. Aryal. India is continuing to supply the country with liquid

oxygen even as it struggles to fill its own domestic need, and

China has sent hundreds of oxygen cylinders, he said.

Dr. Pandey, the medical superintendent of the Trishuli Hospital,

said he has been getting calls from Kathmandu hospitals asking if

he has beds and oxygen available at his hospital. The district

hospital has only 25 Covid-19 beds but is currently caring for 80

patients with the disease, all of them needing oxygen support.

Patients have been streaming in from nearby cities, including

Kathmandu, and the hospital has started running out of its stock of

oxygen, he said.

On Sunday evening, as Mr. Thakur's condition deteriorated and

his family couldn't find a hospital bed elsewhere with a

ventilator, the doctors tried to use a ventilator from the

hospital's ambulance. But the doctors couldn't get the machine to

work properly. A nurse tried to keep Mr. Thakur breathing through

the night using manual bag-mask ventilation, Dr. Pandey said.

"Despite our utmost wish that he live, he died," said Mr.

Thakur's son.

Write to Krishna Pokharel at krishna.pokharel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 18, 2021 11:24 ET (15:24 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

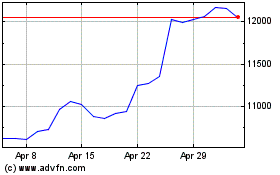

Astrazeneca (LSE:AZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

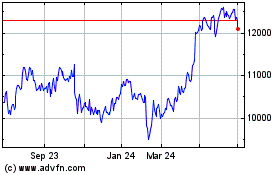

Astrazeneca (LSE:AZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024