By Dave Michaels, Andy Pasztor and Andrew Tangel

Federal authorities are seeking to build a criminal case against

a former Boeing Co. pilot based on statements from U.S. air-safety

regulators who say he failed to provide them crucial details about

the 737 MAX jet's flight-control system, according to people

familiar with the matter.

A pair of Federal Aviation Administration officials who dealt

with Boeing pilot Mark Forkner on pilot-training requirements for

the FAA's approval process years before dual crashes of the MAX are

now considered key witnesses in the investigation, these people

said.

The central role of FAA officials Stacey Klein and William

Schubbe in the criminal probe hasn't been reported before. It

suggests Justice Department prosecutors and federal investigators

are seeking to center a fraud case on claims that Mr. Forkner

misled regulators about how a flight-control feature known as MCAS

worked. Ms. Klein oversaw MAX pilot manuals and training, while Mr.

Schubbe is a manager in the FAA office that helps determine pilot

training requirements for new aircraft.

The automated MCAS system has been blamed for putting two Boeing

737s into fatal nosedives within five months, taking 346 lives,

prompting a global grounding of the fleet and creating the most

serious corporate crisis in Boeing's history.

A case against Mr. Forkner -- who left Boeing for a job with

Southwest Airlines Co. after the MAX was certified by the FAA --

could lead to liability for the Chicago aerospace giant as well.

Prosecutors typically have grounds to charge a company for criminal

conduct once they have formally accused an employee of misconduct.

Mr. Forkner hasn't cooperated with the investigation, according to

people familiar with his situation.

Mr. Forkner's attorneys, David Gerger and Matt Hennessy, said in

a statement that the FAA was aware of how MCAS worked. "As far as

Mark goes, he did his job honestly, and his communications to the

FAA were honest," Mr. Forkner's lawyers said. "As a pilot and Air

Force vet, he would never jeopardize the safety of other pilots or

their passengers. That is what any fair investigation would

find."

Boeing has cooperated with the federal investigations. The plane

maker has said it was investigating the circumstances surrounding

Mr. Forkner's 2016 messages and would share its findings with

authorities. Boeing has faulted flawed engineering assumptions

about how pilots would respond to MCAS cockpit emergencies, and is

devising software and training fixes.

The company, a major defense contractor, has experience dealing

with scandal. In 1989 it pleaded guilty to misusing classified

Pentagon planning documents and paid $5 million in restitution and

fines. In 2006, it paid $615 million to resolve charges of

procurement improprieties and signed onto a deferred prosecution

agreement, meaning it wouldn't be charged unless it failed to

fulfill the terms of the settlement.

Boeing also must navigate an end to a civil investigation by the

Securities and Exchange Commission, one of the people said, which

could allege its disclosures to investors didn't fully communicate

important facts or risks related to the 737 MAX, which analysts had

estimated before the crashes to contribute some 40% of the

company's profit.

Ms. Klein couldn't be reached for comment. Through an FAA

spokesman, Mr. Schubbe declined to comment. The spokesman said Ms.

Klein, Mr. Schubbe and their colleagues are trained to do highly

specialized jobs in a professional manner.

Internal Boeing emails from Mr. Forkner, released over the past

few months, described pressure he felt from Boeing superiors in

2016 and 2017 to persuade the FAA that pilots wouldn't need extra

ground-simulator training on MCAS. Mr. Forkner sent other messages

to Boeing employees indicating that, as part of those efforts, he

misled or provided incomplete information to the agency as well as

airlines and foreign regulators. Congressional investigators, along

with other Boeing critics, have highlighted Mr. Forkner's casual

remarks regarding safety in those messages.

Mr. Gerger, the lawyer for Mr. Forkner, has previously said the

messages should be understood as the comments of employees blowing

off steam "in the ups and downs of their jobs."

A Boeing spokesman declined to comment. A Justice Department

spokesman declined to comment.

Mr. Forkner, who at the time was Boeing's chief technical pilot

for the 737 MAX, persuaded Ms. Klein's group to remove references

to MCAS from aircraft manuals, arguing pilots didn't need to know

about the system because it would rarely, if ever, activate,

according to his emails.

Ms. Klein has been involved in devising new pilot training for

the modified MCAS system, but recently went on leave for a personal

reason unrelated to the criminal investigation and the MAX, a

person familiar with her testimony said. Aaron Perkins, a former

commercial pilot who joined the FAA in 2011 and was involved in the

MAX approval process, has taken over her role vetting training

related to MCAS software fixes.

Mr. Perkins has told prosecutors he feels Mr. Forkner misled him

and his colleagues before the plane went into service, according to

one person familiar with his statements. Through an agency

spokesman, Mr. Perkins declined to comment.

In August 2016, Ms. Klein was among the FAA employees who

participated in test flights of the MAX, which used the final, more

powerful version of MCAS, according to people familiar with the

matter. It couldn't be learned whether those flights involved tests

of MCAS or exposed its potential hazards. An earlier version of the

system worked only at high speeds and was less potent.

Mr. Forkner was thrust into the spotlight last year when it

emerged that in a 2016 instant message he acknowledged misleading

regulators. "So I basically lied to the regulators (unknowingly),"

Mr. Forkner told a fellow Boeing pilot, suggesting he hadn't known

at the time he talked to the FAA that engineers had modified MCAS

to make it more powerful.

Mr. Gerger has said Mr. Forkner was discussing the performance

of a simulator built to mirror the handling of a 737 Max. Mr.

Forkner believed the problem was with that simulator, Mr. Gerger

has said, and not with the plane itself.

Boeing Chief Executive David Calhoun has called Mr. Forkner's

messages "totally appalling," while company representatives

repeatedly have said his communications contradicted Boeing's core

values and commitment to safety.

A spokeswoman for Southwest said Mr. Forkner isn't focused on

MAX-related work and has complied with company and federal

standards applicable to pilots.

Over the months, prosecutors have interviewed current and former

Boeing engineers and pilots, airline pilot-union officials and

various FAA employees, people familiar with the matter said. Mr.

Forkner's former boss Zekeriya Demir is among the other Boeing

employees who have been called to testify before the grand jury

hearing evidence, the people said.

Mr. Demir's testimony hasn't been reported. He couldn't be

reached for comment. The New York Times previously reported that

prosecutors were gathering grand jury testimony about whether Mr.

Forkner misled FAA officials.

Authorities have asked questions about Boeing's safety culture

and production problems with the MAX, the people familiar with the

matter said. Such information could be used to support any criminal

case against Boeing over its communications with regulators, one

person close to the investigation said.

Boeing is paying for attorneys to represent current and former

employees involved in the investigation, including Mr. Forkner,

according to some of the people familiar with the matter.

Any FAA witnesses are likely to face questions about how much

authority the agency delegated to Boeing to assess the safety of

MCAS before the fleet was cleared to fly passengers, people

familiar with the matter said.

Boeing has long insisted the FAA was aware of the system's final

configuration, which was described in a letter and a number of

presentations to the agency. But different groups within the FAA

appeared to only know bits and pieces. An internal FAA review found

Boeing didn't flag the more potent version of MCAS as a system

whose malfunction could cause a catastrophic accident. Such a

designation would have led to more intense FAA scrutiny, The Wall

Street Journal has previously reported.

Asked whether employees in Ms. Klein's FAA training group were

aware of the extent of the modifications to MCAS, FAA chief Steve

Dickson told the Journal in December, "it doesn't appear that they

were."

Before going on leave, Ms. Klein objected to working with Mr.

Forkner's successor, Patrik Gustavsson, who participated in some of

the revealing chat conversations, one person familiar with the

matter said. Federal criminal authorities are also examining

whether Mr. Gustavsson should face charges, another person said.

Mr. Gustavsson couldn't be reached for comment.

--Alison Sider contributed to this article.

Write to Dave Michaels at dave.michaels@wsj.com, Andy Pasztor at

andy.pasztor@wsj.com and Andrew Tangel at Andrew.Tangel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 13, 2020 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

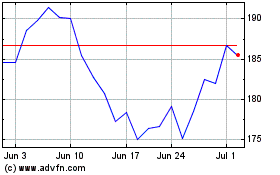

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024