By Andy Pasztor and Andrew Tangel

Boeing Co. got a tentative personal endorsement for fixes to its

beleaguered 737 MAX from the head of the Federal Aviation

Administration after he personally took one of the jets on a test

flight.

"I like what I saw on the flight this morning," said FAA

Administrator Steve Dickson, a former Air Force aviator and senior

airline pilot, after sitting behind the controls for a two-hour

ride over parts of the Pacific Northwest, accompanied by a handful

of pilots who work for Boeing and the FAA.

The agency is in the final phase of a drawn-out process vetting

hardware and software changes to the MAX, particularly to an

automated flight-control system that led to two fatal crashes in

2018 and 2019.

"I felt very comfortable. I felt very prepared based on the

training," Mr. Dickson, still wearing his blue FAA flight suit,

told reporters, referring to Boeing's proposed ground-simulator

training sessions for pilots that would get the MAX back in the

air. "We're in the homestretch, but it doesn't mean we're going to

take shortcuts."

Wednesday's flight -- which Mr. Dickson pledged months ago to

perform -- is one of the last steps intended to allay passengers'

concerns about the MAX's safety before the FAA is expected to clear

the aircraft to resume commercial operations.

"We still have some work to do yet" to respond to public

comments and finalize all of the airplane and training revisions,

Mr. Dickson said. Asked about faltering public confidence in the

FAA's latest oversight of the MAX, the agency's chief responded, "I

don't think you ever stop trying to earn the trust of the

public."

With preliminary support from international air-safety

regulators already in hand and final details of pilot-training

changes expected to be ironed out in coming weeks, the MAX fleet

could secure approval as early as November to return to commercial

service. Widespread passenger flights across the U.S., Europe,

Canada and other regions could follow around the end of the year,

based on internal FAA and carrier timelines.

"There is very little daylight between the authorities on this

project," Mr. Dickson said.

Even after regulators give the go-ahead, individual airlines

will have to complete maintenance checks, conduct

operational-readiness flights and put pilots through extra

ground-based flight-simulator training before starting to carry

passengers again.

Mr. Dickson's unusual flight coincided with the House

Transportation Committee's approval of a bipartisan bill -- weaker

than earlier Democratic proposals -- intended to prevent a repeat

of FAA and Boeing mistakes that ultimately led to a global MAX

grounding in March 2019. Two fatal crashes of the twin-engine jet

within less than five months of each other took 346 lives, created

the biggest corporate crisis in Boeing's 104-year history and

threatened the FAA's stature as the world's pre-eminent air-safety

authority.

Passed on a voice vote with no amendments, the legislation

distills findings of a lengthy investigation by the panel's

Democratic majority, which blamed the FAA and the Chicago plane

maker for missing repeated opportunities -- and lacking adequate

internal safeguards -- to eliminate safety hazards before the

crashes. An automated flight-control feature called MCAS misfired,

overwhelming manual pilot commands and putting both jets into

steep, unrecoverable nosedives.

The bill expands FAA authority to choose and supervise Boeing

employees, called designees, delegated to approve safety systems on

behalf of the government. It also introduces stepped-up

whistleblower protections and civil fines if manufacturers fail to

fully disclose details of essential flight-control systems or seek

to interfere with decisions by FAA designees.

The legislation calls for additional FAA funding and personnel

to handle increasingly sophisticated cockpit automation. But it

doesn't include a proposed provision that would have barred

manufacturers from piggybacking regulatory approvals for heavily

modified versions of certain decades-old plane designs -- as Boeing

did when it created the MAX, a variant of a model that had been in

service since the late 1960s.

The bill calls on outside experts to advise the FAA for the

first time about Boeing's safety culture.

Rep. Peter DeFazio, the Oregon Democrat who is chairman of the

committee, alleged during discussion of the bill Wednesday that

Boeing's corporate "culture of profits at any cost" might have

contributed to company design and communication missteps that left

the FAA largely in the dark about MAX safety hazards.

Echoing conclusions from the panel's sharply worded

investigative report released earlier this month, Mr. DeFazio said

the FAA was "unable or unwilling to conduct rigorous oversight" of

the MAX. The bill "will fix the broken system," he said, predicting

a vote on the House floor later this year.

A Boeing spokesman said the company was grateful for the FAA's

"rigorous process that will lead to the safe return to service of

the 737 MAX" and is ready to meet other requirements set by the

agency and international regulators.

Getting a similar bill to the Senate floor this year appears

significantly less likely, according to industry and government

officials tracking the legislation. The Senate Commerce Committee

hit a stalemate earlier this month over a similar measure that was

abruptly pulled from consideration.

Though supporters portray the House bill as a comprehensive

reform of FAA procedures for certifying the safety of an array of

newly designed aircraft, most of the provisions stem directly from

specific aspects of the MAX saga. Many of the proposed changes were

prompted by technical errors, unfounded assumptions regarding pilot

reaction times and various regulatory loopholes documented by the

committee and outside groups during the crisis.

Meantime, the FAA has taken limited steps independently to

improve internal safeguards and communications while protecting

lower-level employees from undue pressure from agency managers.

Write to Andy Pasztor at andy.pasztor@wsj.com and Andrew Tangel

at Andrew.Tangel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 30, 2020 18:11 ET (22:11 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

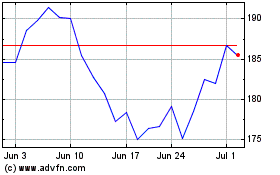

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024