By Katy Stech Ferek

WASHINGTON -- The nation's bankruptcy industry is bracing for a

wave of business collapses triggered by the coronavirus pandemic as

its ranks have been thinned by a decade of economic growth.

The slowed pace of corporate chapter 11 bankruptcy filings --

which crested in 2009 with 13,700 cases and has fallen to about

half that amount in recent years -- has led restructuring firms to

shed bankruptcy lawyers and advisers.

Now the firms are preparing for the rush.

O'Melveny & Myers LLP, Paul Hastings LLP, DLA Piper and

Sidley Austin LLP are among the law firms looking to hire

bankruptcy lawyers at locations across the country, said Dan

Binstock, a partner at Garrison & Sisson who is president of

the National Association of Legal Search Consultants.

Scott Love, a Washington, D.C.-based legal recruiter, calls it a

"frontier free-for-all," adding that "candidates that weren't that

attractive a year ago are now shining."

Restructuring advisory firms are staffing up too, including FTI

Consulting Inc., which began reassigning some of its corporate

finance professionals to handle distress work in March.

Even as firms shift resources, their pool of available talent is

shallow because the bankruptcy practice has been mostly at a lull

in recent years.

"That missing generation -- that's a real thing," said Thomas

Horan, a partner at the Fox Rothschild LLP law firm in Wilmington,

Del. "If you're looking for that midlevel associate who really

knows what they are doing, they are hard to find."

The financial crisis triggered a rise in business failures,

creating full demand for bankruptcy lawyers, restructuring advisers

and legal support businesses. But filings have declined since then,

leading to a contraction of the industry.

Corporate bankruptcy powerhouse Weil, Gotshal & Manges laid

off several dozen associates and more than 100 staffers in 2013,

citing the winding down of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy case. Los

Angeles bankruptcy law firm Stutman, Treister & Glatt shut down

in 2014, leading some of its 25 lawyers to flee for other firms.

Other law firms with large bankruptcy practices have merged.

Shari Bedker, who manages several professional-development

nonprofits for bankruptcy lawyers and restructuring experts, said

she has watched promising young stars drop out of view in recent

years. She has also heard that fewer law students have been

studying bankruptcy because of what were perceived to be bleak job

prospects.

Doron Kenter, a 37 year old who worked on corporate bankruptcy

cases at several top law firms, left the field in 2017 for a

grant-making position at a Jewish nonprofit. He said that he might

have stayed if the industry had remained busy and that he saw other

colleagues use the extra time they had to look for jobs. "I felt

like I was getting stale," he said.

Amy Quackenboss, executive director of the American Bankruptcy

Institute, which represents more than 12,000 professionals, said it

is difficult to predict how many companies will file for chapter 11

bankruptcy protection, the type used by struggling companies to

survive.

Unlike unemployment claims, bankruptcy filings tend to be a

lagging indicator of economic health as business owners spend cash

and look for other ways to stay afloat. J.Crew Group Inc. and

Gold's Gym International Inc. were among the companies filing for

bankruptcy protection this week, and experts see many more

ahead.

Corporate chapter 11 filings increased to 560 new cases during

April, up 26% from 444 filings a year earlier, according to

legal-services firm Epiq Global.

Turnaround Management Association Chief Executive Scott Stuart

said the industry's ability to handle the influx of work will

depend on how quickly it can train newcomers who haven't

experienced an economic downturn to sharpen their skills needed to

guide U.S. companies through uncharted territory.

"It's a legitimate concern that the system is going to be

overwhelmed, but the system isn't going to collapse," said Mr.

Stuart, whose organization is providing extra training materials to

restructuring advisers.

A large portion of lawyers who specialize in big corporate cases

began their careers as young associates shortly after federal

lawmakers made sweeping changes to the bankruptcy code in 1978.

After the law changed, firms ordered younger lawyers to decipher

the new rules. Four decades later that class of lawyers is ready to

retire.

One in every three bankruptcy lawyers graduated in or before

1990, according to Massachusetts-based legal data provider Firm

Prospects LLC, which tracks about 2,200 law firms. For U.S. lawyers

overall, roughly one in every five lawyers graduated at that

time.

"That's a pretty big gap," said Adam Oliver, managing director

at the firm, who said he recalled another generational legal

transition when junior and midlevel lawyers for the real-estate

industry fled during the last recession.

Most of the corporate work will be concentrated in New York and

Delaware, despite several recent legislative efforts to force

companies to file in courtrooms closer to their headquarters. More

than 160 active and retired bankruptcy judges recently wrote a

letter to Congress in support of that requirement, saying

bankruptcies in faraway courts have disenfranchised workers and

local creditors while undermining the integrity of the U.S. court

system.

The expected uptick in bankruptcies will be a test for the

country's roughly 340 bankruptcy judges, most of whom were

appointed after the last peak of corporate filings.

Roughly 45% of the judges who were on the bench during the

depths of the last recession remain in the courts to handle the

next wave, according to a review of federal-court administrative

records and other documents by The Wall Street Journal. Judges are

appointed for renewable 14-year terms.

None of the judges in Wisconsin, Washington state and

Connecticut presided during the last recession. Only one of

Arizona's seven judges and one of Massachusetts's five judges

handled cases during the last rush.

Judicial inexperience has a high cost, according to a 2017 study

from researchers at Brigham Young University, the University of

Minnesota, Queen's University and the University of Illinois.

In that study of more than 100,000 chapter 11 bankruptcy cases

filed between 1993 and 2012, researchers found that corporate

bankruptcy cases assigned to less experienced judges spend more

time in court as those judges take longer to make decisions and

issue rulings.

It concluded that it takes an average of four years for a

bankruptcy judge to learn how to manage complex chapter 11 cases as

efficiently as their experienced colleagues.

Courtroom delays account for potentially billions of dollars in

extra legal fees, the study said.

A Massachusetts bankruptcy judge, Frank Bailey, was appointed

during the heat of the last recession and estimates that his own

learning curve took two years. He said that new bankruptcy judges

lean on each other for help and that the lull has led brighter

lawyers to the bench because private practice became less

lucrative.

"Most bankruptcy judges come to the bench with a lot of

experience, either on the business side or the consumer side, but

everyone has something to learn," he said.

Write to Katy Stech Ferek at katherine.stech@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 06, 2020 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

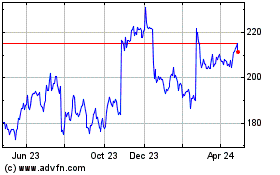

FTI Consulting (NYSE:FCN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2024 to May 2024

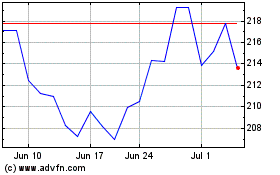

FTI Consulting (NYSE:FCN)

Historical Stock Chart

From May 2023 to May 2024