By Mark Hulbert

The stock market's return over the next decade is likely to be

well below historical norms.

That is the unanimous conclusion of eight stock-market

indicators with what I consider the most impressive track records

over the past six decades. The only real difference between them is

the extent of their bearishness. (See chart below.)

Of course, it is impossible to say that there aren't other

indicators with even better long-term records than these eight. But

I'm not aware of any.

To illustrate the bearish story told by each of these

indicators, consider the projected 10-year returns to which these

indicators' current levels translate. The most bearish projection

of any of them was that the S&P 500 would produce a 10-year

total return of 3.9 percentage points annualized below inflation.

The most bullish was 3.6 points above inflation.

Even the bullish end of that range is more than 3 annualized

percentage points below the stock market's inflation-adjusted

return over the past 200 years.

The most accurate of the indicators I studied was created by the

anonymous author of the blog Philosophical Economics. It is now as

bearish as it was right before the 2008 financial crisis,

projecting an inflation-adjusted S&P 500 total return of just

0.8 percentage point above inflation. Ten-year Treasurys can

promise you that return with far less risk.

Bubble flashbacks

The only other time it was more bearish (during the period since

1951 for which data are available) was at the top of the

internet-stock bubble.

The blog's indicator is based on the percentage of household

financial assets -- stocks, bonds and cash -- that is allocated to

stocks. This proportion tends to be highest at market tops and

lowest at market bottoms.

According to data collected by Ned Davis Research from the

Federal Reserve, this percentage currently looks to be at 56.3%,

more than 10 percentage points higher than its historical average

of 45.3%. At the top of the bull market in 2007, it stood at

56.8%.

Ned Davis, the eponymous founder of Ned Davis Research, calls

the indicator's record "remarkable." I can confirm that its record

is superior to seven other well-known valuation indicators analyzed

by my firm, Hulbert Ratings.

To figure out how accurate an indicator has been, we calculated

a statistic known as the R-squared, which ranges from 0% to 100%

and measures the degree to which one data series explains or

predicts another.

In this case, zero means that the indicator has no meaningful

ability to predict the stock market's returns after inflation over

the next 10 years. On the other hand, a reading of 100% would mean

that the indicator is a perfect predictor.

Since 1954, according to our analysis, the Philosophical

Economics indicator had an R-squared of 61%. In the messy world of

stock-market prognostication, that is statistically significant.

Our analysis begins in that year because that is the earliest date

for which data are available for all of the other indicators that

we studied.

The other seven

So, here's a look at those other indicators back to the 1950s,

listed in descending order of their R-squareds:

-- The Q ratio, with an R-squared of 46%. This ratio -- which is

calculated by dividing market value by the replacement cost of

assets -- was the outgrowth of research conducted by the late James

Tobin, the 1981 Nobel laureate in economics.

-- The price/sales ratio, with an R-squared of 44%, is

calculated by dividing the S&P 500's price by total per-share

sales of its 500 component companies.

-- The Buffett indicator was the next-highest, with an R-squared

of 39%. This indicator, which is the ratio of the total value of

equities in the U.S. to gross domestic product, is so named because

Berkshire Hathaway Inc.'s Warren Buffett suggested in 2001 that is

it "probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at

any given moment."

-- CAPE, the cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio, came next

in the ranking, with an R-squared of 35%. This is also known as the

Shiller P/E, after Robert Shiller, the Yale finance professor and

2012 Nobel laureate in economics, who made it famous in his 1990s

book "Irrational Exuberance."

The CAPE is similar to the traditional P/E except the

denominator is based on 10-year average inflation-adjusted earnings

instead of focusing on trailing one-year earnings.

-- Dividend yield, the percentage that dividends represent of

the S&P 500 index, sports an R-squared of 26%.

-- Traditional price/earnings ratio has an R-squared of 24%.

-- Price/book ratio -- calculated by dividing the S&P 500's

price by total per-share book value of its 500 component companies

-- has an R-squared of 21%.

According to various tests of statistical significance, each of

these indicators' track records is significant at the 95%

confidence level that statisticians often use when assessing

whether a pattern is genuine.

However, the differences between the R-squareds of the top four

or five indicators I studied probably aren't statistically

significant, I was told by Prof. Shiller. That means you're

overreaching if you argue that you should pay more attention to,

say, the average household equity allocation than the price/sales

ratio.

The bulls' response

What do the bulls say about all this? To find out, I turned to

Jeremy Siegel, a finance professor at the Wharton School of the

University of Pennsylvania.

Prof. Siegel is perhaps best known as the author of "Stocks for

the Long Run," in which he argues that buying and holding equities

for the long term is the best advice for most investors.

In an interview, Prof. Siegel questioned the strength of these

indicators' statistical foundation. He says their historical

records contain peculiarities that traditional statistical tests

don't adequately correct for. Once corrected, Prof. Siegel suspects

that their R-squareds would be significantly lower.

Prof. Siegel also questions whether these indicators are really

as bearish as they seem. Among the theoretical objections he lodged

against these indicators:

-- Accounting-rule changes in the 1990s. After those changes, he

says, readings from the traditional P/E and the Shiller P/E were

higher than before, so their recent levels aren't particularly

comparable to those from previous decades.

-- The Buffett indicator has lost any relevance it may have once

had because of the increasing proportion of U.S. corporate sales

coming from overseas. That dynamic also artificially inflates the

indicator and makes it appear more bearish than it should be, Prof.

Siegel says.

-- The Q ratio provided insight at a time when our economy was

dominated by capital-intensive manufacturing companies, but not

when it is dominated by high-tech information-age firms.

"What is the replacement cost for a Google or a Facebook?" Prof.

Siegel asks rhetorically.

It can't be determined, however, whether correcting for these

issues would transform the message of any of these indicators from

bearish to outright bullish. Prof. Shiller of Yale, for one, says

he isn't aware of any indicator that currently is forecasting

above-average returns over the next decade and sports a

statistically significant record back to at least the 1950s.

Regardless, it is important to emphasize that, no matter how

impressive the statistics underlying the indicators may be, they

don't amount to a guarantee that the stock market will struggle

over the next decade.

After all, as Prof. Siegel reminds us, most of these indicators

have been bearish for years now, even as stocks have enjoyed one of

the most powerful bull markets in history.

Furthermore, even if stocks turn out to be lower in a decade's

time, none of these indicators tells us anything about the path

that the market takes along the way. It might immediately head

south from here, or it could enter a blowoff phase of sharply

higher prices before succumbing to a severe bear market.

A leaf in a hurricane

Calling short-term trends is difficult, if not impossible. For

instance, when it comes to calling one-year returns, Prof. Shiller

said in an interview that he doesn't know of any valuation

indicator with a record extending as far back as the 1950s whose

predictive power is significantly better than zero.

Ben Inker, co-head of the asset-allocation team at GMO, draws an

analogy to a leaf in a hurricane: "You have no idea where the leaf

will be a minute or an hour from now. But eventually gravity will

win out, and it will land on the ground."

Mr. Hulbert is the founder of the Hulbert Financial Digest and a

senior columnist for MarketWatch. He can be reached at

reports@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 05, 2018 22:26 ET (02:26 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

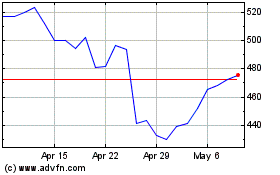

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024