By Christopher Mims

Short of living in a remote hut while forsaking cellphones, the

internet and credit cards, there is no longer any way that you, as

an individual, can prevent marketers, governments or malicious

actors from gathering and using comprehensive, personally

identifying information about you.

There are things you can do to reduce the amount of information

you leak. You could, for example, ask Facebook to delete your

browsing history, or perhaps one day you'll be able to pay the

company to not track you. But keeping up requires more time,

sophistication and paranoia than most of us can muster. And it

still isn't 100% effective.

There has been a sea change in how data about all of us is

gathered and distributed. Those who want information about us no

longer have to observe us directly. They can now collect our data

from our friends, contacts -- even people we don't know. Preserving

privacy used to be about protecting ourselves and our devices. Now,

the information is outside of our control, stored in address books

of friends and latent in our social networks and family ties.

As in cybersecurity, protection of some of our most important

personal data now depends on protecting the weakest link in the

systems of which we are a part.

Genuine privacy or anonymity is over, if we ever had it, says

Paul Francis, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Software

Systems in Germany. "All we can really hope to do is, piece by

piece, get better at protecting privacy," he adds.

Those pieces might come from unexpected places. The very

companies currently taking fire for collecting and disseminating

our personal information -- Google and Facebook -- could someday be

stewards of it, or else be disrupted by those who are willing

to.

Why our data isn't safe

The Cambridge Analytica scandal -- where 270,000 people who

downloaded an app led to a data breach for 87 million Facebook

users -- is the first large-scale example of the importance of

maintaining "group privacy," says Yves-Alexandre de Montjoye, head

of the computational privacy group at Imperial College London.

In a hypothetical example, Prof. de Montjoye's group reported

that if just 1% of cellphones in London were compromised with

malware, an attacker would be able to continuously track the

location of more than half the city's population.

Our vulnerability to such attacks is compounded by another

phenomenon: It's easy to identify us with just a tiny amount of

information, making it impossible to render any pool of data about

a population anonymous.

Facebook, Google and others in the ad-tech space say they take

pains to "anonymize" the data they collect on us. This

anonymization consists of mathematical tricks allowing them to

market to us while assuring that they can't identify us for other

purposes -- and no one else can either.

But time and again, researchers with access to pools of

anonymized data have found ways to identify individuals within it,

Prof. de Montjoye says.

The Max Planck Institute's Dr. Francis co-founded a company,

Aircloak, to develop software to protect data. Diffix, as it's

called, sits between a database and its owners, allowing them to

make specific queries but never revealing the whole database. It

should allow firms like banks to protect user data internally, in a

way that makes them compliant with sweeping new privacy rules under

Europe's General Data Protection Regulation, according to Dr.

Francis and Sebastian Probst Eide, Aircloak's chief technical

officer.

But even special software can't help online advertising

companies get fully compliant with the European regulations -- at

least not yet. Early on, the Aircloak team abandoned an attempt to

anonymize targeted advertising, because there are so many

transactions that can identify a person, Dr. Francis says. For

example, a company advertising medication for certain conditions

could inadvertently identify people who click on the ad and then

potentially share that information with others in the chain of

custody of personal data.

Big Tech: From villain to savior?

If technology can't keep personal info out of the hands of the

tech giants, the seemingly paradoxical alternative is to collect

all of that personal info in one place, so that a central authority

can handle it.

That central authority could be a government. Estonia, for one,

has created a cryptographically secure universal ID to which any

kind of personal data can be attached, from taxes and financial

records to health data. As a result, Estonians can e-file their

taxes in about 5 minutes, patients can view a digital paper trail

of everyone who has ever accessed or altered their medical records,

and even non-Estonian residents can become "e-residents" who gain

many of the online rights and privileges afforded to Estonia's

citizens.

Such an authority could be granted to a tech giant like

Facebook, Google, Apple or Amazon.

Giving companies like Facebook and Google even more of our data

might seem like the opposite of protecting it. But both companies

already have the start of the infrastructure required to support

such a massive undertaking: It's the identity systems that allow us

to log into other sites and apps using our Facebook, Google or

Amazon credentials.

This could be an opening for Apple, Amazon or some new entrant

to become a personal-data custodian. The idea of a centralized

repository (a.k.a. personal-data store), which marketers would have

to seek permission to access, has been proposed before. But these

projects -- which depend on some companies having our data, and

others not -- haven't taken off, since gathering and using our data

is both legal and lucrative.

With GDPR, Europe has an opening for such a service, and if any

of the privacy regulations proposed in the U.S. gain traction,

conditions could ripen here as well. It's also possible people

could experience a change of mind-set -- realizing some data is

fair game but some tracking goes too far -- to create the kind of

demand for privacy-protecting products and services that is

currently scarce.

Write to Christopher Mims at christopher.mims@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 06, 2018 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

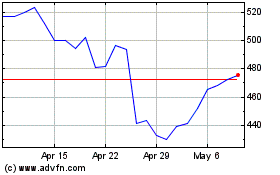

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024