By Denise Roland

Danish drug giant Novo Nordisk AS is living through a corporate

nightmare that any CEO might recognize from business school.

After the company concentrated on making essentially one product

better and better -- and charging more and more -- customers have

suddenly stopped paying for all that improvement. The established

versions are, well, good enough.

In Novo Nordisk's case, that product is insulin, a hormone that

is deficient in people with diabetes. Since its founding in 1923,

the company has made successive waves of better insulin. It is the

world's biggest producer of the stuff, and insulin brings in more

than half of the company's revenue.

Over the years, that innovation has translated into an ability

to charge more and more for the latest version, boosting profit

margins and swelling the company's stock price. As diabetes -- an

incurable disease -- morphed into a global epidemic in recent

years, Novo Nordisk's tight focus on insulin provided reliable and

growing profits.

Lately, that flow ended. Doctors, health-plan managers and

insurers all have balked at paying for Novo Nordisk's newest

version of its insulin. Clinical trials show it works as promised

in controlling diabetes and delivers significant side benefits

compared with its predecessors. But for many customers, all that

isn't enough to warrant paying more -- because the older drugs on

the market already work pretty well, too. In Europe, the company

had hoped to price Tresiba at 60%-70% higher than its previous

product.

"The incremental improvements don't seem to justify the premium

prices," said Steve Miller, chief medical officer of Express

Scripts Holding Co., one of America's biggest pharmacy-benefit

managers, a key middleman that buys drugs in bulk on behalf of

insurers.

Novo Nordisk's hopes for the new drug -- which it once expected

to generate blockbuster profits -- have dimmed. The company has

warned repeatedly it won't meet its long-term growth targets, and

its stock price has shrunk by more than a quarter since the

beginning of last year. Executives are scrambling to diversify --

pouring money into research outside its core insulin-focused

science. The company announced 1,000 job cuts last fall.

"A lot of staff -- anyone who joined within the last 18 years --

had not seen anything but success and constant growth," said Chief

Executive Lars Fruergaard Jørgensen in an interview.

As the turmoil at Novo Nordisk shows, there are commercial

limits to innovation. Nokia Corp. and BlackBerry Ltd. both lost

their market dominance in smartphones because competitors beat them

with major technological advances. Both firms are in the process of

reinventing themselves.

In other cases, though, innovation has hit a wall. That is

especially the case in some pockets of the pharmaceuticals

business, where the scope for big improvements is narrowing.

Common, deadly ailments, such as asthma, high cholesterol and

heart disease, were the focus of the pharmaceutical industry during

a golden age of drug launches in the 1990s. Now, building on those

advances has proven costlier and more complex, and usually results

in smaller gains. Incrementally improved medicines are harder to

sell at the prices needed to cover their development costs.

Sanofi SA and Amgen Inc. are struggling to make headway with

their new cholesterol-lowering drugs. These medicines, known as

PCSK9 inhibitors, bring about a greater reduction in cholesterol

levels than older statins alone for certain people. But the

companies have yet to convince insurers that it is worth putting

these patients on them: Both cost more than $14,000 a year before

rebates and discounts. Older statins are available for just pennies

a day.

Novartis AG hoped its new heart-failure medicine Entresto's

proven superiority to older, so-called ACE-inhibitors would

guarantee rapid uptake among cardiologists. But insurers initially

incentivized doctors to prescribe older, cheaper drugs, leading to

a much slower launch. That is changing as insurers gradually adopt

more permissive policies toward Entresto.

People with diabetes don't make enough insulin, a hormone needed

to convert sugar into storable energy. In Type 1 diabetes, the body

doesn't make insulin at all. In Type 2, the far-more-common form

linked to obesity, the body develops resistance to insulin, and the

pancreas cannot produce enough for the proper effect.

Around 12% of American adults have diabetes, according to an

estimate published this year by the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, though around a quarter of those aren't aware they have

the disease. That figure could rise to as many as one in three

American adults by 2050, according to a 2010 report by the CDC.

Of those diagnosed with diabetes, about a third depend on

insulin injections, the CDC said. That was about six million people

in 2011.

Novo Nordisk has been making insulin since the hormone was

discovered in the early 20th century. That breakthrough, by two

Canadian scientists, led to the first effective treatment for

diabetes.

August Krogh, a Danish medical professor and Nobel laureate,

heard about the discovery in 1922 while lecturing in the U.S. with

his wife, Marie, a doctor who suffered from Type 2 diabetes. After

a stopover in Toronto, the couple returned to Denmark with

permission to manufacture the lifesaving treatment in

Scandinavia.

Nordisk Insulinlaboratorium was founded the next year. Denmark,

home to one of Europe's biggest pork industries, made sense for a

business based, in its early days, on harvesting the hormone from

the pancreases of pigs and cows.

In 1924, two brothers left Nordisk to set up their own firm,

Novo. The rival companies competed fiercely, one-upping each other

with insulin innovations, such as injections with longer

effects.

Novo adopted new genetic engineering technology in the 1980s.

The technology ushered in synthetic human insulin and ended the

dependence on animals. The two companies joined forces in 1989,

leapfrogging America's Eli Lilly & Co. as the world's biggest

insulin producer.

Over its history, the company's narrow focus was a strength: Its

deep expertise boosted its ability to produce ever-better

products.

Through the 1990s, the company tweaked the basic insulin

molecule to fine-tune its performance. It developed a fast-acting

insulin, called Novolog, that enters the blood quickly, providing a

ready boost at mealtimes. It also rolled out a long-acting version

called Levemir that releases a steady stream of insulin into the

blood throughout the day.

In the mid-2000s, Novo Nordisk launched a handful of these

so-called analog insulins, as patients clamored for more convenient

forms. Doctors, patients and health-care managers in the U.S. and

Europe were appreciative, willing to pay more for the new

benefits.

Novo Nordisk's stock surged. By 2013, Copenhagen's tiny stock

exchange was forced to change its blue-chip benchmark index to keep

it from being overwhelmed by the company's swelling market

value.

By then, Novo Nordisk enjoyed a duopoly for its longer-acting

drug, competing only with French giant Sanofi SA.

After the success of Levemir, Novo Nordisk aimed higher. It

developed Tresiba, even more convenient: The drug can be taken at

any time of day, whereas Levemir and Sanofi's equivalent, Lantus,

require a regular dosing schedule. In addition, Tresiba is

associated with fewer episodes of dangerously low blood sugar, or

hypoglycemia.

An early set of results for Tresiba impressed executives, Novo

Nordisk's research chief, Mads Thomsen, recalled. "We just sat

there and said, 'Wow,' " he said. "We had kind of realized we were

very close to perfection."

As it awaited final blessing from the U.S. Federal Drug

Administration, the company rolled the drug out across Europe,

starting in 2013. It hit the market with a thud.

Drug pricing in Europe is very different from the U.S. The

biggest buyers aren't insurance companies and health-plan managers,

but government-controlled entities or their middlemen. They

typically negotiate hard with companies for supplies for an entire

country. The system keeps prices lower than in the more-fragmented

U.S. system.

Once a price is set by one of these bodies, it is very difficult

to raise. So, drug companies typically launch a new drug at the

highest price they think they can get, knowing they won't likely be

able to increase it.

Novo Nordisk, however, struggled from the start to convince

European buyers that Tresiba was different enough from Levemir to

command a big premium.

In Germany, for example, a pricing board set the price for

Tresiba at the same level as the basic synthetic human insulin that

had been available since the 1980s, which has none of the

long-acting or other special benefits of newer forms. An agency

that assesses the cost-benefit of new medicines concluded Tresiba

had no real advantage in terms of controlling the disease itself.

Novo Nordisk withdrew Tresiba from Germany, Europe's largest drug

market.

Other countries, like the Netherlands, Denmark and Spain,

allowed Novo Nordisk to launch Tresiba at around its desired price

of 60%-70% higher than Levemir and Sanofi's Lantus.

But to minimize the impact on their budgets, the health systems

wouldn't reimburse patients for Tresiba, and the new insulin gained

very little market share. Last year, Novo Nordisk lowered its price

to a level that the health systems would reimburse, and use of

Tresiba has picked up.

"In Europe, we launched with a very high premium," said Mr.

Jørgensen, the CEO. "That turned out to be too high." He said

Tresiba's premium over Levemir and Lantus is now around 20% in most

European markets.

Still, executives were sanguine. Prices in Europe were now

locked in at much lower rates than they had expected. But they

thought they could rely on the U.S. market to more than make up. In

the U.S., drugmakers usually introduce new products at a modest

premium over previous versions, with the assumption they will be

able to raise prices for years to come.

Novo Nordisk launched Tresiba in the U.S. in early 2016, ahead

of the presidential election. Politicians on both sides were

slamming drug companies for raising prices. Beyond the campaign

rhetoric, insurers and health-plan managers were targeting diabetes

medicine, in particular, for cost-cutting scrutiny. The medicines

are their second-largest drug outlay, after cancer medicines,

according to analyst Ronny Gal of investment research firm

Bernstein.

Payers were girding for expected cost increases related to a

raft of new cancer-fighting drugs, many of which promised big gains

for patients. In the diabetes field, a string of new, pricey drugs

designed to control blood sugar levels in early-stage Type 2

patients were also stretching budgets. These pressures made

insulin, where the older products worked pretty well, an obvious

target for cost savings.

Diabetes "is on payers' radar with big, red, flashing lights,"

said Barry Farrimond, a European drug-pricing analyst at ZS

Associates, a management consultancy.

Amid that environment, Novo Nordisk couldn't convince executives

at pharmacy-benefit managers such as Express Scripts that Tresiba

was enough of a game-changer to warrant a significantly higher

price.

For that, large clinical groups like the American Diabetes

Association "have to tell us that this medication is clearly

superior and as a result everybody who has diabetes should have

access to it," said Troyen Brennan, chief medical officer of CVS

Health Corp., another large pharmacy-benefit manager.

Doctors and the ADA view Tresiba as "not much different," he

said. This year's ADA guidelines group Tresiba alongside other

long-acting insulins and note that patients with well-managed, Type

2 diabetes can use basic synthetic human insulin "safely and at

much lower cost."

Novo Nordisk accepted a list price for Tresiba only around 10%

higher than Levemir. The list price doesn't take into account

rebates and other concessions, and some pharmacy-benefit managers

are charging a higher copay for Tresiba to steer patients to

cheaper drugs.

At the same time, Novo Nordisk was being hit by another new

threat: competition. Eli Lilly, which for years had mostly played

in the short-acting insulin market, launched a low-cost,

longer-acting one, pressuring prices even more.

"We knew the dynamics were going to change, but it ended up

being more dramatic than we anticipated," CEO Mr. Jørgensen said in

the interview.

This month, he told reporters the price for Tresiba would take

another hit in 2018, having already fallen in 2017. "The

competitive environment we are in is now a permanent situation," he

said.

Tresiba is gradually gaining traction. As of June, it had

grabbed a 6.2% share of the U.S. long-acting insulin market,

according to health data provider Quintiles IMS. That momentum

helped Novo Nordisk post better-than-expected earnings in the

second quarter this year, leading the company to brighten its

full-year outlook.

But the tougher U.S. pricing environment took executives by

surprise. Last year, the company slashed its long-term

profit-growth forecasts twice: in February, to 10% from 15%, and in

October, to 5%.

The company's breakneck growth of the past two decades is "an

era that's over for now," said Claus Johansen, senior portfolio

manager at Danske capital, a top-15 investor in the company.

The company is protected from some market forces. In a quirk of

its Danish ownership structure, a foundation owns the majority of

the company, shielding it from an opportunistic takeover.

The Tresiba experience has prompted a strategic overhaul. Mr.

Jørgensen, who had been chief executive-designate since September

2016 and formally took up the role in January, has pivoted the

company away from making incremental improvements to insulin.

"The market will probably not be screaming to get a slightly

better Tresiba," he said in a February investor call.

It is widening its research to diseases that the company

considers "adjacent" to diabetes. Novo Nordisk has long had a

sideline in hemophilia treatments but has generally refrained from

dabbling in other diseases. Now, it will start investigating drugs

for conditions like NASH, a disease in which fatty deposits build

up in the liver; diabetic kidney disease; and cardiovascular

disease.

Within the diabetes field, the company still makes and sells the

popular, less-expensive insulins. A Novo Nordisk drug called

Victoza is part of a new class of treatments that boost insulin

production in Type 2 diabetes patients. And it hasn't given up on

insulin research altogether. In October, it scrapped a project

working on a tablet version of the medicine. Instead, it is now

focusing on more meaningful improvements, such as "smart insulin"

that acts only in the presence of high blood sugar.

"I still believe we will bring new insulin to the market," said

Mr. Jørgensen. "But the innovative height has to be better than

what we have today."

Write to Denise Roland at Denise.Roland@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 15, 2017 11:12 ET (15:12 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

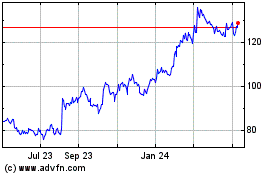

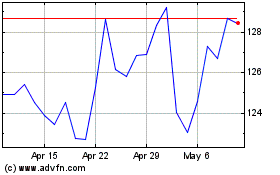

Novo Nordisk (NYSE:NVO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Novo Nordisk (NYSE:NVO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024