Angola charged four men in alleged plot to siphon $500 million

from nation's reserves

By Margot Patrick, Gabriele Steinhauser and Patricia Kowsmann

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (October 4, 2018).

An accountant walked up to a teller at a suburban London branch

of HSBC Holdings PLC and asked to transfer $2 million to Japan. The

teller pulled up the account and stared at her screen. There was

$500 million in the account.

After asking the accountant some questions, she told him she

couldn't make the transfer. Then she filed a report to her

superiors.

HSBC quickly found out where the money had come from. Three

weeks earlier, in mid-August of 2017, officials at the central bank

of Angola had sent $500 million of the country's reserves to a

company registered to the accountant's modest storefront office

between a cafe and barber shop in a gritty London neighborhood.

Authorities in Angola now allege the $500 million transfer was

illegal, part of a convoluted plot to defraud the southern African

country in the final weeks of President José Eduardo dos Santos's

38-year rule. If Angolan prosecutors are right, the HSBC teller had

helped thwart one of the biggest attempted bank heists ever.

Investigators unraveling the transaction for Angola have

identified a cache of forged bank documents and an "Ocean's

Eleven"-style cast of characters, including a smooth-talking

Brazilian based in Tokyo and a Dutch agricultural engineer. Their

alleged plan, said Angolan government officials in court documents

and interviews with The Wall Street Journal, was to siphon fees and

cash from the central bank while pretending to set up a $35 billion

investment fund.

The group convened in glamorous spots in London, a coastal

resort in Portugal and Angola's capital, Luanda, with at least one

meeting attended by President dos Santos. The money trail they left

led investigators to international banks, shell companies and a

Japanese firm whose mission is described on its website as "assets

liberation."

"One looks at this and thinks, 'Wow, what's going on here?'"

says José Massano, Angola's new central-bank governor, who is

trying to piece together how his bank almost lost a chunk of its

foreign-exchange reserves. "It is the kind of thing that shouldn't

really happen."

Last month, prosecutors in Angola announced a variety of

criminal charges against a son of Mr. dos Santos, the former

central-bank governor and two others in relation to the alleged

fraud. In the U.K., Angola has sued four men, including the

Brazilian and the Dutch engineer, to recover EUR25 million the

central bank paid to set up the multibillion-dollar fund, which

never materialized.

The defendants in the U.K. civil case deny wrongdoing and say

they did legitimate work on an investment fund, under contract, for

which they received fees. After being named a suspect by Angola

prosecutors in March, Mr. dos Santos's son said he is cooperating

with the investigation, and the former central-bank governor

couldn't be reached for comment. One of the other two men charged

denied wrongdoing; the other couldn't be reached for comment.

Angola's lawyers say the country may have fallen victim to a

decades-old type of get-rich-quick scheme, typically used to

defraud individuals or companies, not sovereign states. Investors

are told they can make huge returns through a private market in

"bank guarantees." There is no such market, and the U.S. Treasury

Department and Securities and Exchange Commission have warned that

such offers are always fraudulent.

This account of the case is based on interviews with Angolan

officials, bankers, people involved in the legal cases and

documents related to the U.K. lawsuit, including sworn statements

and a judicial ruling.

In June of last year, a letter marked "confidential" arrived at

Angola's finance ministry for then-President dos Santos, 76 years

old, who was preparing to step down after elections that August.

Angola was reeling from double-digit inflation, and its currency

had plunged since the 2014 oil bust.

The letter, bearing a BNP Paribas SA logo and the signature of

the French bank's chairman, made a compelling proposal. BNP Paribas

and other European banks would help Angola create a $35 billion

fund, refinance debt and get hard currencies for imports.

The letter named two deal coordinators: Hugo Onderwater, a Dutch

agricultural engineer living in Portugal, and Jorge Pontes

Sebastião, a childhood friend and business partner of President dos

Santos's son. Mr. Pontes, 40, a slim man whose bodyguard carries

his briefcase to meetings, was until recently president of an

Angolan bank; Mr. Onderwater, 55, tall and sandy-haired, has a

business converting waste to energy, according to U.K. court

filings by the two men. The two had met in 2016 to discuss

financing for an Angolan government food-quality agency, then

broadened the idea into an Angola investment fund, according to a

court statement by Mr. Pontes.

Days after the letter arrived, Angola's finance minister and

central-bank governor flew to a meeting in Cascais, near Lisbon.

The president's son, José Filomeno dos Santos, then in charge of

Angola's sovereign-wealth fund, came with them to represent the

state, according to a U.K. court filing. His father had approved

looking into the project, according to Mr. Pontes's statement.

In a seaside hotel, Mr. Onderwater, the Dutch engineer, and Mr.

Pontes presented slides for a new fund to help diversify Angola's

economy, to be managed by a "qualified trust company" in London,

according to excerpts from the presentation in U.K. court

documents. A slide listed banks said to be supporting the project,

including the European Central Bank.

The ECB says it was never involved in the project, and BNP

Paribas says the letter with its logo and chairman's signature was

forged.

Mr. Onderwater later told the U.K. court the banks mentioned

were merely examples of possible participants, and that he only saw

the BNP Paribas letter during court proceedings.

Angola's finance minister, Archer Mangueira, was skeptical of

the plan. His department questioned the experience of the two deal

coordinators and wondered about the project's "true

developers."

Nevertheless, in July of last year, the central-bank governor,

Valter Filipe da Silva, signed an agreement with Mr. Pontes to set

up the fund.

That same month, the central bank started transferring EUR24.85

million ($28.9 million) from its Commerzbank AG account in

Frankfurt to an account of Mr. Pontes at Banco Comercial Português

SA in Lisbon, for fees due under the agreement, U.K. court

documents show.

Mr. Onderwater received EUR5 million of that money, using some

to buy property in Lisbon and rural Devon, England, investigators

for the Angolan finance ministry found.

Another EUR2.4 million went to a Tokyo company called Bar

Trading, headed by another alleged participant in the plan,

51-year-old Brazilian Samuel Barbosa da Cunha. His role was to act

as "trustee" of Angola's $500 million seed money for the new fund,

in charge of obtaining the "bank guarantees" and financial

instruments that were supposed to transform the country's money

into $35 billion, according to Mr. Pontes's testimony and other

U.K. court filings.

Mr. Pontes told the U.K. court Mr. Barbosa was brought into the

deal by Mr. Onderwater, a claim Mr. Onderwater denies. Lawyers for

Mr. Onderwater said recently in a written statement that the bank

guarantee was "solely an internal Angolan matter."

Bald and hulking, Mr. Barbosa described himself as an expert in

buying and selling such guarantees on his company website and in

correspondence with clients reviewed by the Journal. His LinkedIn

biography says he has 30 years of financial experience and an

economics doctorate from Boston University. The school's library

has no record of a dissertation, and a spokeswoman for the school

couldn't confirm his attendance or a degree after searches by his

name, hometown and birthdate.

At the end of July 2017, Mr. Barbosa headed for London. First,

he touched down in Riga, Latvia, where he boasted to a friend that

he was working on a big deal with Angola's central bank, the friend

says.

Mr. Barbosa and the friend had teamed up before, persuading

retirees in Florida and Canada and an Australian company to invest

in bank guarantees promising up to 550% monthly returns, according

to people who gave them money and documents they provided to those

people, which were reviewed by the Journal. A representative of the

Australian company filed complaints about the friend and Mr.

Barbosa to U.K. authorities, alleging fraud, according to the

documents.

U.K. regulators declined to comment. Mr. Barbosa didn't respond

to requests for comment, and the friend denied working with Mr.

Barbosa or any involvement in the alleged fraud.

One day in August of last year, Messrs. Onderwater and Pontes

sent instructions to the central-bank governor to transfer $500

million to the trustee, Mr. Barbosa, according to evidence cited by

the U.K. court. They provided the details of an HSBC account of a

company called Perfectbit Ltd., registered to the London

accountant's storefront office and listed on Bar Trading's website

as an overseas subsidiary.

Two days later, central-bank officials entered Perfectbit's

account details into the Swift network, a bank-owned consortium

that handles millions of daily payment instructions. The money

moved from the central bank's Standard Chartered PLC account in

London to Perfectbit's HSBC account. The transaction didn't prompt

any extra checks by either bank, people familiar with the matter

say.

"There is a hole in the international finance system that allows

for transfers to be made with minimal information," says Shane

Shook, a cybersecurity consultant.

The central bank's Swift message code indicated -- inaccurately

-- that the money was for intrabank business with HSBC rather than

headed to an HSBC customer, according to bank documents reviewed by

the Journal. HSBC noticed the discrepancy later, when it started

probing the transfer.

Once the $500 million was in Perfectbit's account, the

accountant made Mr. Barbosa and an associate owners of the company.

The accountant, Bhishamdayal Dindyal, kept signing power on the

HSBC account.

Over the next few weeks, the accountant and an associate of Mr.

Barbosa's each visited HSBC branches trying to access the cash,

unsuccessfully, according to Angola's U.K. court claim. The

associate said in a later court statement that $26,999.99 from the

HSBC account was paid as a fee for Perfectbit's work on the

fund.

After the alert teller in the suburban London branch filed a

report about the enormous balance, HSBC suspended the account for

review.

In Angola, a power shift was under way. President João Lourenço,

inaugurated in September 2017, launched an anticorruption drive,

and his finance minister, Mr. Mangueira, still suspicious of the

central bank's new investment fund, started an investigation.

Seeking answers, Mr. Mangueira took the central-bank governor,

Mr. da Silva, to London again to meet with the three organizers of

the deal -- Messrs. Onderwater, Pontes and Barbosa. The former

president's son, Mr. Filomeno dos Santos, came along, too, this

time in support of the deal organizers, U.K. court filings

show.

In an hourslong meeting at the elegant Cavalry & Guards

Club, Mr. Barbosa batted away questions about his and his

colleagues' qualifications. He said a European bank had guaranteed

Angola's $500 million, according to a U.K. court filing. That day,

a letter was sent to President Lourenço saying Angola's $500

million was guaranteed by Switzerland's Credit Suisse AG, and had

swelled to $2.5 billion from transactions by the trustee.

Credit Suisse says it didn't guarantee the money and documents

in its name were forged.

As he listened to Mr. Barbosa, Mr. Mangueira recalled in an

interview, he became convinced the Brazilian was the mastermind of

a fraud. He had the air of a " vendedor da banha da cobra," Mr.

Mangueira said -- Portuguese for a snake-oil salesman.

Back in Angola, President Lourenço gave Mr. da Silva, the

central-bank governor, 24 hours to get the $500 million back,

according to U.K. court filings. That didn't happen, and he

resigned without any public explanation.

With the deal collapsing, Perfectbit wrote to HSBC last Nov. 9

asking the bank to return the nearly $500 million in its account to

the central bank, according to a U.K. court statement from Mr.

Barbosa. He said Perfectbit was asked to make the request by the

company owned by Messrs. Pontes and Onderwater that had hired

Perfectbit to act as trustee.

Eight days later, Angola's finance ministry filed the U.K.

lawsuit against the three organizers of the deal -- Messrs. Pontes,

Onderwater and Barbosa -- and Mr. Barbosa's associate. A judge

froze the $499,972,438 remaining in the HSBC account. The U.K.'s

National Crime Agency, an entity akin to the Federal Bureau of

Investigation, opened a criminal investigation.

A few days later, Mr. Barbosa's associate was arrested by police

at Heathrow Airport and released under investigation. He denies

wrongdoing.

The accountant, Mr. Dindyal, who isn't a defendant in the

lawsuit, was arrested at home in December and also released under

investigation. He declined to comment.

Messrs. Pontes, Onderwater and Barbosa all say their companies

operated under contracts with the central bank or each other and

deny wrongdoing.

A judge in the U.K. civil case said in a written April ruling

that Mr. Pontes and his company "appear to contend (in effect) that

they are victims of a fraud perpetrated by Mr. Onderwater. Mr.

Onderwater appears to contend (in effect) that he is a victim of

the fraud of Dr. Barbosa and Dr. Pontes."

U.K. authorities returned the $500 million to the Angolan

central bank, but prosecutors in Angola are proceeding with their

criminal fraud case.

They charged Mr. Filomeno dos Santos, the former president's

son, and Mr. Pontes with money laundering, criminal association,

falsification of documents, influence peddling and stealing through

fraud.

Mr. da Silva, the former central-bank governor, was charged with

criminal association, embezzlement and money laundering. The fourth

man, a central-bank employee, was charged with criminal association

and embezzlement.

Mr. Filomeno dos Santos was dismissed from the sovereign-wealth

fund this year. He hasn't commented since the charges were

announced. In a previous statement to Angola state television, he

said he was cooperating with the investigation.

Mr. Pontes denies the criminal charges. In an email statement

through his lawyers, he said Angola's EUR24.85 million was

voluntarily returned in June as part of negotiations to settle the

U.K. civil case, and that he will "continue to act in good faith in

his commercial dealings."

The former central-bank governor, Mr. da Silva, hasn't commented

publicly and couldn't be reached for comment.

Messrs. Onderwater and Barbosa likely will keep their payments

unless Mr. Pontes takes his own legal action against them,

according to people familiar with the U.K. civil case, which

remains open.

In June, several photos appeared on Mr. Barbosa's Facebook page.

One shows him puffing on a cigar, another grinning from a

business-class cabin.

Write to Margot Patrick at margot.patrick@wsj.com, Gabriele

Steinhauser at gabriele.steinhauser@wsj.com and Patricia Kowsmann

at patricia.kowsmann@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 04, 2018 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

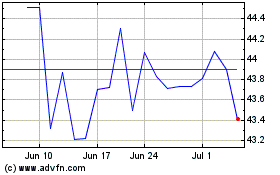

HSBC (NYSE:HSBC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

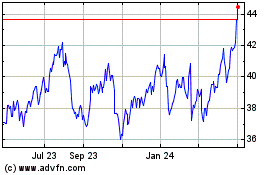

HSBC (NYSE:HSBC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024