By Liz Hoffman

In the spring of 2014, Las Vegas tycoon Sheldon Adelson floated

an offer to David Solomon: come run his casino empire.

Mr. Solomon, a senior Goldman Sachs Group Inc. executive, had

been Mr. Adelson's banker since the 1990s. He had honed his craps

game on weekend jaunts to Atlantic City. He was 52 years old and

seen as a long shot to become chief executive of Goldman.

But Mr. Solomon turned down the job, according to Michael Leven,

who was Mr. Adelson's second-in-command at the time. Mr. Adelson

wasn't willing to give up day-to-day control, and Mr. Solomon

didn't want to be an understudy.

That patience paid off for Mr. Solomon, who this week was

anointed the heir apparent to Goldman Chief Executive Lloyd

Blankfein.

After a decade atop Goldman's investment-banking division, Mr.

Solomon won a year-long competition with co-president Harvey

Schwartz, who announced his resignation Monday. The handoff from

Mr. Blankfein could be announced as soon as year-end, according to

people familiar with the matter.

Mr. Solomon's path could hardly be more different from that of

Goldman's two most-recent chief executives. Mr. Blankfein rose

through the firm's trading operation. His predecessor, Henry

Paulson, came up as a white-shoe banker, covering industrial

companies in the Midwest.

Mr. Solomon, in contrast, started out in the mercenary world of

high-yield debt. He added boardroom experience as he rose, building

an unusually diverse list of clients that includes Mr. Adelson,

Fidelity Investments, 3M Co., private-equity firm Leonard Green

& Partners and co-working firm WeWork Cos.

He doesn't fit the mold of a classic investment banker, who

typically spends formative years on the road wooing corporate

executives. Rather, Mr. Solomon is known as a screw-turning

operator who can get things done.

"David is a 'buck stops here' kind of guy," said John Danhakl,

managing partner of Leonard Green. "If there's a disagreement or

something we want Goldman to know, he's the guy we call. And when

the firm occasionally has to tell us 'no,' he does that in such a

straightforward, unapologetic way that you can't help but respect

it."

That reputation helped Mr. Solomon earn the top job. Mr.

Blankfein and the rest of Goldman's board were impressed with the

debt-underwriting business he had built, which last year had record

revenues, according to people familiar with the matter. Also in his

favor, the people said, were some 150 meetings Mr. Solomon had

taken with clients of Goldman's securities division over the past

15 months.

Executives say he is patient and exacting -- skills that should

help Goldman as it tackles a plan to grow annual revenue by $5

billion. "He grinds," one colleague said.

Mr. Solomon grew up in Scarsdale, N.Y., working summers at the

local Baskin-Robbins. After graduating from Hamilton College, where

he played rugby and was social chair of his fraternity, he arrived

on Wall Street in 1986 at Drexel Burnham Lambert.

He started off selling commercial paper, then moved to junk

bonds. His early clients were an eclectic bunch united by their

need for money: industrial conglomerates like Dow Chemical Co.,

private-equity and real-estate firms, and investors such as Mr.

Adelson and Ronald Perelman.

After Drexel failed, Mr. Solomon went to Salomon Brothers and

then Bear Stearns, both known as sharp-elbowed, transactional

firms.

"Bear was a commission shop. David wanted to get into the

relationship business," said Howard Morgan, a private-equity

executive who has been friends with Mr. Solomon since college. "He

used to say even then that if there was any one place he'd like to

work, it was Goldman. The white-shoe aspect -- that mattered to

him."

Mr. Solomon got his chance in 1999. He joined to run leveraged

finance, part of a wave of outside hiring around Goldman's initial

public offering. Three years in, he was put in charge of

stock-underwriting, a move that marked him inside the firm as an

executive on the rise.

In 2006, Mr. Solomon was named a co-head of investment banking,

overseeing several thousand merger and underwriting bankers.

He is credited with professionalizing that division, once a

loose collection of fiefs. Business-unit heads came to dread his

year-end compensation roundtables, where Mr. Solomon would question

raises that were once routinely granted and insist on weeding out

underperformers.

Some longtime bankers lamented what they saw as a decline in

collegiality and autonomy. A few rainmakers left after sparring

with Mr. Solomon, including Christopher Cole, Howard Schiller and

Gordon Dyal, according to people familiar with the matter.

But the makeover worked. Over Mr. Solomon's 10 years running the

investment bank, profit margins nearly doubled, and the division's

share of Goldman's revenue rose to 22% from 11%. The unit buoyed

Goldman's results as trading slowed after the global financial

crisis.

Mr. Solomon has worked to ease Goldman's sweatshop culture,

tracking the hours worked by the firm's young bankers and

instituting strict limits for those not working on active deals.

"You have to create an atmosphere where people can work hard, but

they also have opportunities to have a life," he said on a Goldman

podcast last year.

He has also recruited and promoted more women. When running

investment banking, he pushed the firm's recruiters to assemble

incoming classes that were 50% female, and last summer presented a

plan to Goldman's board of directors to take that effort firmwide.

He helped bring senior women including private-equity banker

Sarah-Marie Martin to the firm, and tapped Stephanie Cohen, a

merger banker, as Goldman's strategy chief last year.

Mr. Solomon has flexed his muscles in other ways. He lobbied Mr.

Blankfein to add Daniel Dees, a senior Goldman technology banker,

to its management committee last year, according to people familiar

with the matter. Mr. Dees' position hasn't traditionally carried a

seat on the committee. The move rankled some senior investment

bankers, even as it bolstered Mr. Solomon's reputation as a manager

with muscle.

Mr. Solomon has flirted with jobs outside Goldman over the

years. In addition to Mr. Adelson's offer to run Las Vegas Sands

Corp., Mr. Solomon also talked with private-equity firm TPG Capital

in 2015 about joining as its co-CEO, people familiar with the

matter said. That job eventually went to a former Goldman partner,

Jon Winkelried.

--Joann S. Lublin contributed to this article.

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 15, 2018 10:32 ET (14:32 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

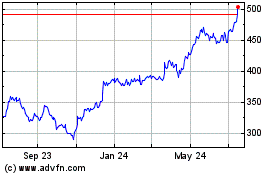

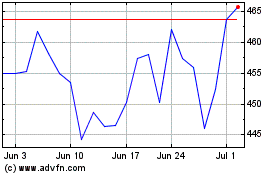

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024