More than ever, investors need total-market exposure to avoid

creating a portfolio of losers

By Mark Hulbert

Index funds are going to become even harder to beat than they

already are.

That is because we are increasingly becoming a "winner take all"

economy dominated by a relatively few big players. Since no one has

shown the ability to determine in advance who these winners will

be, much less predict when one era's winners will stumble and be

eclipsed by the next generation's, owning all stocks is the only

realistic strategy for avoiding owning a portfolio of losers.

"Networking effects" are driving the winner-take-all economic

shift, according to Geoffrey Parker, a professor of engineering at

Dartmouth College. These effects come into play, Prof. Parker says,

whenever a company's users create value for other users. An

illustration is Apple Inc.'s dominance of the smartphone industry:

As more people buy iPhones, the more developers want to develop

apps for those phones. And the more good iPhone apps there are, the

more people want to buy those phones. These networking effects

create a "virtuous cycle" in which one, or perhaps a handful of

companies, eventually dominates the competition.

Networking effects themselves aren't new, Prof. Parker notes.

But in the past, they were constrained by high transaction costs.

To use another phone analogy, from a century ago, growth of the

early telephone network at first was slow because it was expensive

to add new users, and placing a call required a human intermediary.

Fast forward to today, Prof. Parker says, and "transaction costs

are plummeting, allowing network effects to become paramount."

This virtuous cycle shows up particularly in a widening of

profit margins at dominant firms. That is because, as Prof. Parker

points out, "a lot of the cost structure of networked firms is

fixed." So just as these dominant firms' revenue is growing as they

attract more users, their profits margins are expanding markedly as

well.

Attention on Snap

Investors are clearly betting that Snap Inc. will be one of the

next big winners.

At its initial public offering price on the New York Stock

Exchange in early March, the company known for its popular

disappearing-message app Snapchat was trading at a sky-high

price-to-sales ratio of almost 50. That was higher than any other

large-company IPO in U.S. history, according to Jay Ritter, a

finance professor at the University of Florida (defining a large

company as having at least $200 million in inflation-adjusted

sales). And Snap today is trading even higher than where it came to

market.

Note carefully that the shift toward a winner-take-all economy

merely makes it possible that Snap will live up to the huge growth

expectations implicit in its high price/sales figure -- not

probable.

In fact, Prof. Ritter points out, the shift actually makes it

likely that Snap will fail to generate the profits necessary to

justify a $20 billion valuation, since by definition there are more

losers than winners in the winner-take-all economy.

In any case, the winner-take-all shift has been accelerating in

recent years. Take the percentage of total income at publicly

traded U.S. corporations that is earned by the top 100 firms. This

percentage grew to 52.8% from 48.5% between 1975 and 1995,

according to research conducted by finance professors Kathleen

Kahle of the University of Arizona and Rene Stulz of Ohio State.

Over the subsequent 20 years, it mushroomed to 84.2%.

That means that the overwhelming majority of publicly traded

corporations in the U.S. earn either modest profits or actually

lose money. A related development is the drop in the number of

publicly traded firms. It peaked at more than 7,500 in the late

1990s, according to Profs. Kahle and Stulz, and by 2015 stood at

3,766. Indeed, the professors wonder if we may be witnessing the

coming to pass of a forecast made in 1989 by Harvard Business

School's Michael Jensen, who predicted the "demise of the public

corporation."

Investor impact

There are a host of broader implications of these developments

for economic policy makers as well as long-term consequences for

investors. Harry Deangelo, a professor of finance and business

economics at the University of Southern California, says that in a

winner-take-all economy, it is more important than ever to invest

in a portfolio of all stocks. Only in that way can you be assured

of owning the winning companies' stocks and not a basket of

mediocre or losing companies, he says.

Another consequence of the shift is greater volatility at the

level of the individual stock. A single misstep by an erstwhile

winner can have an outsize influence by triggering an exit of

previously loyal users -- which could in turn lead to an

"unvirtuous cycle" downward. Dartmouth's Prof. Parker illustrates

this point by asking us to imagine what would happen to Apple's

stock if its next iPhone release is a flop.

The typical stock's exaggerated vulnerability to even slight

changes in the way the wind is blowing is also illustrated by the

growing percentage of the stock market's combined value that comes

from intangibles. According to Ocean Tomo, a firm that focuses on

intellectual property, 84% of the S&P 500's market value now

comes from intangible assets. In 1975 it was just 17%.

More stocks needed

Another reason to own all stocks: According to Martin Lettau, a

finance professor at the University of California, Berkeley, even

though the typical individual stock has become more volatile in

recent years, the overall market hasn't. This is because individual

stocks' greater volatilities offset each other, Prof. Lettau says,

with the bigger zigs of one stock balancing out the larger zags of

another. As a consequence, he says, investors today need to own a

much larger number of stocks than investors in previous generations

to construct a stock portfolio that is no more volatile than the

overall market.

The easiest way to become adequately diversified, of course, is

by investing in an index fund.

Index funds also are the cheapest ways for individual investors

to do that. Schwab recently lowered the expense ratio on its ETF

that is benchmarked to the entire U.S. stock market, Schwab U.S.

Broad Market ETF (SCHB). It now costs just 0.03% a year, or $3 per

$10,000 invested. Vanguard's Total Stock Market ETF (VTI), is only

barely behind with an expense ratio of 0.05%.

Mr. Hulbert is the founder of the Hulbert Financial Digest and a

senior columnist for MarketWatch. He can be reached at

reports@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 10, 2017 02:48 ET (06:48 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

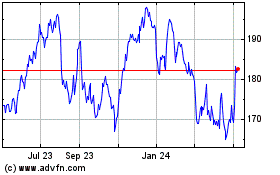

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

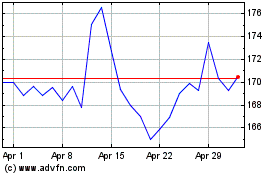

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024