U.S. court says firm needn't turn over personal data stored on

computers abroad

By Devlin Barrett and Jay Greene

Microsoft Corp. won a major legal battle with the U.S. Justice

Department Thursday when a federal appeals court ruled that the

government can't force the company to turn over emails or other

personal data stored on computers overseas.

The case, closely watched by Silicon Valley, comes amid tensions

between Europe and the U.S. over government access to data that

resides on the computers of social-media and other internet

companies.

The ruling is another setback for the Justice Department's

efforts to force technology companies to comply with government

orders for data, following the collapse earlier this year of two

cases involving Apple Inc.'s refusal to help open locked

iPhones.

The ramifications of Thursday's ruling by the Second U.S.

Circuit Court of Appeals in Manhattan could be sweeping. If the

appeals court's legal rationale stands, it also could influence

companies' and their customers' decisions about how and where to

store data. It also alter the course of talks between the U.S. and

other governments, in terrorism and criminal cases, about access to

evidence stored in servers on foreign soil.

Much of the data lately sought in such probes by European

investigators is kept on servers in the U.S. European officials,

particularly in Belgium, have complained that the current legal

framework makes it difficult to detect and prevent plots such as

the bombing of the Brussels airport earlier this year.

A Justice Department spokesman said Thursday's ruling undermines

public safety, and suggested the department might appeal to the

Supreme Court.

"We are disappointed with the court's decision and are

considering our options," the spokesman said. "Lawfully accessing

information stored by American providers outside the United States

quickly enough to act on evolving criminal or national- security

threats that impact public safety is crucial to fulfilling our

mission to protect citizens and obtain justice for victims of

crime."

In a statement, Microsoft President and Chief Legal Officer Brad

Smith called the decision "a major victory for the protection of

people's privacy rights under their own laws, rather than the reach

of foreign governments."

The company had argued that the U.S. government's position

violated national sovereignty and would open the door to other

countries seeking data stored in the U.S.

"As a global company, we've long recognized that if people

around the world are to trust the technology they use, they need to

have confidence that their personal information will be protected

by the laws of their own country," Mr. Smith said.

The case arose from a 2013 warrant issued by a federal judge in

New York for the emails of a suspect in a drug-trafficking probe.

Some of that data resided on Microsoft computers in Ireland.

Microsoft computers in Ireland. Microsoft fought the order in

court, arguing that it shouldn't be forced to comply with a U.S.

court order demanding data held in another country.

The Justice Department had argued that because Microsoft is

based in the U.S., the government has the authority to get the data

even if it is stored elsewhere, and asserted that there was no

conflict with Irish or European privacy laws.

Other major tech companies -- including Amazon.com Inc., Verizon

Communications Inc. and Cisco Systems Inc. -- as well as lobbying

groups such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Software

Alliance, filed legal briefs supporting Microsoft.

The case is part of a broader fight between Silicon Valley and

Washington over how much authority the government has to force

technology companies to help them gather data in investigations.

The companies argued that revelations about U.S. spying with the

help of telecom companies have heightened foreign sensitivities and

placed U.S. firms at a competitive disadvantage abroad.

In their legal briefs, Justice Department lawyers argued a

Microsoft victory could lead some American customers to claim a

foreign country of residence "for the specific purpose of evading

the reach of U.S. law enforcement."

In past cases, U.S. courts enforced subpoenas issued to banks

for business records held abroad, even when foreign law prohibited

it. The Second Circuit held in a 1984 ruling that control over

records, not their location, is what counts in such cases.

But Microsoft lawyers drew a distinction between business

records and emails. "A bank can be compelled to produce the

transaction records from a foreign branch, but not the contents of

a customer's safe-deposit box kept there," they wrote in their

Second Circuit brief. "A customer's emails are similarly private

and secure and not subject to importation."

Alex Abdo, an attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union,

said the ruling exposes the failure of Congress to modernize

privacy laws for the digital age so they spell out more clearly

how, when, and how much data can be searched by the government, and

make the process more transparent.

"It's shameful that Congress has yet to fix the flaws in our

privacy laws," said Mr. Abdo. "In the same way that a court ruling

on the National Security Agency phone program forced Congress'

hand, this may too."

In the ruling, the appeals court concluded Congress didn't

intend the warrant provisions of the Stored Communications Act to

apply beyond U.S. borders.

"The focus of those provisions is protection of a user's privacy

interests," the judges wrote. "Accordingly, the SCA does not

authorize a U.S. court to issue and enforce an SCA warrant against

a United States-based service provider for the contents of a

customer's electronic communications stored on servers located

outside the United States."

The ruling is the largest legal victory for Microsoft to date in

a number of disputes with the government about searches of its

customers' data.

In April, Microsoft sued the Justice Department, challenging the

constitutionality of government orders barring tech companies from

telling customers when federal agents have examined their data.

That case is pending.

The company in 2013 also challenged restrictions that limit the

disclosure of details regarding secret orders to turn over user

data in U.S. surveillance efforts sought under the Foreign

Intelligence Surveillance Act. That matter was resolved in 2014

when the government agreed to permit tech companies to publish some

aggregated data about such orders.

Jennifer Daskal, a professor at American University in

Washington who specializes in criminal and national security law,

said the government almost certainly would appeal, given the

stakes.

"One of the most notable pieces of this case is the degree to

which the court recognizes how emails and internet-service

providers are different from banks and business records. They

refused to extend the banking analogy to emails and recognized the

distinct privacy issues at stake with personal communication," Ms.

Daskal said.

The ruling, she said, puts "an enormous amount of pressure" on

what all sides agree is the outdated and poorly-functioning current

legal framework for cross-border data requests, and is likely to

lead to greater calls for Congress to update electronic privacy

laws.

Write to Devlin Barrett at devlin.barrett@wsj.com and Jay Greene

at Jay.Greene@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 15, 2016 02:48 ET (06:48 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

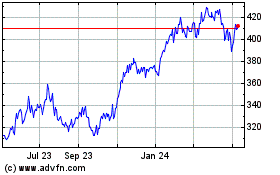

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

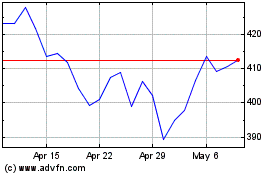

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024