By Sarah E. Needleman

Videogames are a go-to tool for tech-savvy teachers looking to

engage students. Now Microsoft Corp. thinks schools are ready to

pay to add one of the most popular games ever to the

curriculum.

Microsoft this summer plans to launch a classroom edition of its

building-block game "Minecraft," which it acquired in 2014 when it

paid $2.5 billion for Mojang AB. The company is planning to charge

$5 a student annually and is figuring out per-school licensing fees

for larger educational institutions.

The potential payoff could be significant. About 50.2 million

students are expected to be enrolled in U.S. public schools this

year, from prekindergarten through high school, with roughly a

further 4.9 million in private schools, according to the National

Center for Education Statistics.

Microsoft isn't targeting specific grades or usage, said Matt

Booty, who oversees "Minecraft" as a vice president for Microsoft's

games studio. The game would be available to teachers, principals

and administrators, from elementary school through college.

"We would like to have all those avenues open," Mr. Booty said.

He declined to discuss sales projections.

Spending on educational software and digital resources in the

U.S. for prekindergarten through 12th-grade classrooms reached

$8.38 billion in 2014, up 5.1% from a year earlier and up 12% since

2010, according to the latest data from the Software &

Information Industry Association. The association doesn't break out

sales of educational-games software.

Videogames have found their way into schools for decades. "The

Oregon Trail," a 1971 computer game that challenged players to

survive a wagon ride across 1800s America, came bundled with school

computers. More modern hits such as "The Sims" are used to help

students solve problems and collaborate. The physics-based gameplay

of "Angry Birds" has been a popular teaching tool.

In "Minecraft," players are digital architects with endless

space to build any object imaginable, from a replica of the Taj

Mahal to a medieval castle or even entire cities. In sophisticated

cases, builders incorporate real-world tools such as a working

mobile phone that streams video.

Since its 2009 release, the game has sold more than 70 million

copies for personal computers, smartphones and consoles such as

Microsoft's Xbox One. A mobile version consistently ranks among the

top paid apps world-wide on Apple Inc. and Alphabet Inc.'s

stores.

The coming "Minecraft: Education Edition" includes special

features for the classroom. For instance, teachers can customize

projects, track students' progress and save their creations.

Students get personal accounts tied to their school identification

cards and can share digital photos of their works.

"Minecraft" is made up of "great material, but it's

supplementary," said Mike Kaspar, a senior policy analyst at the

National Education Association, which represents public-school

teachers and personnel. "There's no way it can cover what teachers

need to cover as far as content goes in a classroom," he added. "It

would be a great product for an after-school program."

Proponents, though, say "Minecraft" hones an array of skills,

including critical thinking, geometry and teamwork.

Joel Levin taught computer technology for a decade in New York

elementary schools. In 2011, he co-founded TeacherGaming LLC, which

developed a modified version of the game called "MinecraftEdu" to

make it easier for teachers to incorporate it in their lessons.

"The applications of 'Minecraft' are incredibly diverse," he

said. To date, his Finland-based startup has sold copies to more

than 7,000 schools world-wide, generating about $3 million in

revenue.

TeacherGaming in October agreed to sell "MinecraftEdu" to

Microsoft for an undisclosed sum. The deal is pending but expected

to go through. Microsoft used the so-called mod version to create

the new educator edition.

One of the biggest hurdles in selling "MinecraftEdu" to schools

has been "getting teachers over the fear factor of using a tool in

the classroom that kids are more familiar with than they are," Mr.

Levin said. "They feel like the student."

Schools, meanwhile, have cumbersome approval processes for

purchasing software, strict rules around safety and privacy, and

outdated computers that aren't powerful enough to run modern games

software, Mr. Levin said.

Microsoft doesn't plan to advertise the new edition beyond

promoting it at teacher conventions. The company intends to

announce the new edition at a conference Tuesday. Its biggest

challenge might be getting educators to pay for software when so

many classroom-friendly games already exist free online or come

bundled with textbooks.

Bethany Petty, a high-school teacher in Park Hills, Mo., uses

free software to motivate her students. Once she spent $2 on a game

her entire classroom could use, which she paid for out of her own

pocket, she said.

"I would have no problem going to my principal" to buy software,

she said, but finding good games that cost little or nothing has

always been "pretty easy."

Write to Sarah E. Needleman at sarah.needleman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 19, 2016 06:14 ET (11:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

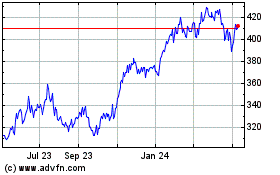

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2024 to May 2024

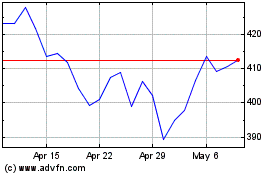

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Historical Stock Chart

From May 2023 to May 2024