By Paul Ziobro | Photographs by Daniel Acker for The Wall Street Journal

DECATUR, Ill. -- Norfolk Southern Corp. executives, employees

and customers holed up for five days recently to work on a complex

puzzle. How could they unclog a sprawling freight yard in central

Illinois without triggering chaos?

They asked a multitude of small questions akin to word problems

in a math class. Their answers point toward some of the most

sweeping changes to the nation's railroad system in decades.

There are 19 railcars bound for Kansas City that reach Decatur

around 7:10 a.m. most days, about two hours before their connecting

train. That isn't enough time to unhook the cars, which are loaded

with freight like coiled steel and corn syrup, move them along a

grid of tracks, then attach them to the outbound train. So they sit

in Decatur for an average of 26 hours -- well over Norfolk

Southern's goal of 20.

Pushing back the Kansas City departure to 2:30 a.m. the

following day would fix that problem but generate another: 21 cars

from Conway, Pa., would miss the train to Kansas City. One fix

would be to have the Conway train arrive later.

"It's a cascade," says Todd Reynolds, general manager of Norfolk

Southern's western region.

Freight railroads generally have operated the same way for more

than a century: They wait for cargo and leave when customers are

ready. Now railroads want to run more like commercial airlines,

where departure times are set. Factories, farms, mines or mills

need to be ready or miss their trips.

Called "precision-scheduled railroading," or PSR, this new

concept is cascading through the industry. Under pressure from Wall

Street to improve performance, Norfolk Southern and other large

U.S. freight carriers, including Union Pacific Corp. and Kansas

City Southern, are trying to revamp their networks to use fewer

trains and hold them to tighter schedules. The moves have sparked a

stock rally that has added tens of billions of dollars to railroad

values in the past six months as investors anticipate lower costs

and higher profits.

The new approach was pioneered by the late railroad executive

Hunter Harrison, who engineered turnarounds at two major Canadian

railroads and Jacksonville, Fla.-based CSX Corp. by radically

revamping their logistics.

His template won over Wall Street by boosting profits and stock

prices, but it generated chaos on the tracks. The 2017 revamp at

CSX caused crippling congestion east of the Mississippi River,

jeopardizing operations at plants that made Pringles potato snacks,

threatening deliveries of McDonald's french fries and idling

Cargill Inc. soybean-processing plants because of lack of

railcars.

The challenge for Norfolk Southern, which operates in the

Eastern U.S., and others is to make sure that doesn't happen again.

Federal regulators, flooded with complaints about CSX, which also

operates in the East, have pledged to scrutinize other companies

adopting a similar strategy.

"The board does not want to see any carrier implement so-called

PSR the way CSX did," said Ann Begeman, chairman of the Surface

Transportation Board, the federal agency that oversees freight

railroads. "It had unacceptable impacts on so many of its shippers

and, frankly, other carriers."

CSX spokesman Bryan Tucker said the company could have done

better communicating the changes to customers, but he defended the

actions by pointing to its financial results. He said CSX trains

are running faster and with less downtime, and the railroad is

hauling more cargo with fewer locomotives, railcars and

employees.

Norfolk Southern estimates that its own plan will similarly

allow its system to operate faster and more efficiently, while

cutting about 3,000 employees from its current workforce of about

26,000 and shedding 500 locomotives from its fleet of about

4,100.

Ideally, the end result would be a more fluid railroad network

that operates much like a moving conveyor belt, with fewer jams. It

would allow shippers and customers to ship finished goods on a

just-in-time basis, reducing carrying costs across the board.

Norfolk Southern is starting its overhaul with a process it

calls "clean sheeting," which involves dismantling and reassembling

schedules and processes -- one yard at a time.

The Decatur rail yard, which contains 180 miles of track on a

550-acre plot, is the largest flat-switching yard in Norfolk

Southern's system. The yard connects to two other railroads, and

several large customers nearby have plants adjacent to the yard,

including Archer Daniels Midland Co. corn and soybean processing

plants.

During the recent five-day work session, Norfolk Southern Senior

Vice President Michael Farrell outlined the railroad's objectives

to a group Norfolk executives, union workers and customers gathered

at the downtown Decatur Club.

"We're here to build it from the ground up," he said. "When we

come out of here on Friday, we will have a plan. Then, it comes

down to execution."

Later that day, in the basement of the railroad's Decatur

office, about two dozen members of the team pored over data on

timetables, track lengths and the makeup of the 15 trains that stop

daily at the terminal. Operations executives who had performed

similar exercises at other Norfolk Southern yards drilled workers

about how long it took to perform tasks such as switching cars

between trains and turning around a locomotive.

Executives pieced together new outbound schedules by working

backward. Their goal was to reduce "dwell" -- downtime railcars

spend in the yard -- to around 20 hours, on average, for the 1,200

to 1,500 cars handled daily. Figuring out how to get the largest

blocks of arriving cars to leave sooner was the priority.

The yard has four receiving tracks where eastbound trains pull

in to get rearranged based on destination. One Norfolk Southern

executive suggested using two of those tracks to park strings of

railcars heading out on the same train so the outbound train can be

rebuilt more quickly. Two union workers pointed out that plan would

cause problems if more than two trains arrived at nearly the same

time, as can happen when trains arrive late.

Railroads like Norfolk Southern are essentially 20,000-mile

outdoor assembly lines that have to contend with weather, broken

tracks and derailments. Mr. Farrell, the Norfolk Southern senior

vice president, reminded those attending the meeting that the goal

would be to overcome problems and get back to the plan as quickly

as possible. "You manage the exceptions," he said. "Become

exception managers."

Norfolk Southern said it is bringing customers in during the

planning and development process to head off the kinds of problems

that have plagued other railroads. "They're all open to that

approach," Chief Executive Officer James Squires said of the

customers. "Many of them want to see results. They want to feel

confident that there will be no network disruption."

Christopher Boerm, Archer Daniels Midland's president of

transportation, declined to comment on the proposed changes at the

Decatur yard, but said ADM wants to see rail service improve and

appreciates "the opportunity to voice our concerns and help our

rail partners understand our specific business challenges and

needs."

Some Norfolk customers who have seen similar changes play out at

other railroads say they are skeptical. They say that while

railroad operators profess to be sensitive to customer needs, the

changes proposed are still largely take-it-or-leave-it.

Many customers of railroads own their own freight cars. Norfolk

Southern wants customers to prune their car fleets. It promises to

cycle cars quicker from plant to customer and back.

Customers say they don't want to give up that buffer of railcar

supply, especially in industries where the price of goods sold is

tied to commodities markets, or where demand can shift quickly

because of outside factors such as weather or tariffs. Some

shippers don't see Norfolk Southern's approach as much different

than CSX's. "It's still doing less with less, and not charging any

less," said one rail shipper.

Mr. Squires said Norfolk Southern "will be pursuing pricing that

is commensurate with the value of our services."

BNSF Railway Co., which operates alongside Union Pacific in the

Western U.S., has resisted the industrywide push to cut capital

spending and drastically change service plans. Executive Chairman

Matthew Rose, who is scheduled to retire this month, said railroads

that cut back on service risk pushback from regulators. Mr. Rose

said BNSF, owned by Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway Inc., is

focused on carrying more loads. "More volume leads to more

investment," he said.

Norfolk Southern, Kansas City Southern and Union Pacific all had

service issues last year that they said exposed the perils of

maintaining the status quo. When, in some cases, they responded by

adding cars to handle the extra volume, congestion in some

corridors got worse.

As Union Pacific tried to clear gridlock, it experimented with

some strategies modeled after Mr. Harrison's, which it then decided

to adopt more broadly.

"We came to the realization that experimenting with pieces of

precision-scheduled railroading was less effective on our network

than going the whole way," said Chief Executive Lance Fritz. The

catalyst, he said, "was nothing more complex than our growing

frustration and our customers' growing frustration with the service

product at that time."

Norfolk's Mr. Farrell, a 53-year-old former All American

wrestler at Oklahoma State University, previously worked at both

Canadian railroads where Mr. Harrison's plan went into effect --

Canadian National Railway Co. and Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd. At

Norfolk Southern, he spent more than a year crisscrossing the

network as a consultant to identify problem spots, a process he

jokingly called the longest-ever episode of "Undercover Boss."

After he formally joined the company in November, he ramped up

clean-sheeting sessions. As of mid-February, the railroad says,

trains were running 13% faster and dwelling 20% less in yards

compared with last year.

Its operations executives are fanning out to more locations each

week to rework operations. Once local operations are fine-tuned,

Norfolk Southern plans to more broadly overhaul how trains move

across its network.

Norfolk Southern's promise to shareholders is that it will lower

its operating ratio -- the percentage of revenue consumed by

operating costs -- to 60% by 2021, from 65.4% in 2018. CSX and

Union Pacific are racing to get their operating ratios below 60%

sooner, in part by cutting capital expenditures.

Norfolk Southern is holding its capital spending to between 16%

and 18% of revenue, compared with less than 15% for Union Pacific

and about 13% for CSX. It will be upgrading its locomotive fleet

and adding equipment so that it can carry more trailers -- a

business thriving, in part, from more e-commerce packages crossing

the country.

Weeks after the clean-sheeting session in Decatur, the new plan

is up and running at the yard. Mr. Reynolds, the regional manager,

said most tracks are now used for the same purpose each day,

simplifying operations. Railcars are making their connections more

reliably and spending less time in the yard. And in a sign that

customers are buying in, he said, fewer cars are sitting idle in

the yard.

Write to Paul Ziobro at Paul.Ziobro@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 03, 2019 10:58 ET (14:58 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

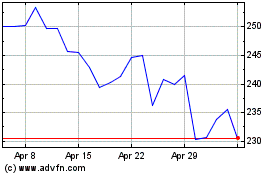

Norfolk Southern (NYSE:NSC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Norfolk Southern (NYSE:NSC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024