UPDATE: FDIC Reviews Insurer Disclosures On Retained-Asset Accounts

August 12 2010 - 4:34PM

Dow Jones News

Sheila Bair, the head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.,

said her agency is reviewing the disclosures life insurers send to

beneficiaries to determine if they mislead consumers about whether

her agency backs their accounts.

Bair cited "potential confusion" by consumers as a reason for

the review of the so-called retained-asset accounts. When a policy

holder dies, some insurers put beneficiaries' funds into the

interest-bearing accounts and send them checkbooks to allow them to

drawn down the funds instead of sending a single check for the full

amount of their payout.

At least some insurers have both their company's name and the

name of a bank that acts as an intermediary on their checks.

"Public understanding of FDIC insurance and when and how our

guarantee applies is of the highest importance to us," Bair wrote

in a letter to Therese Vaughan, the chief executive of the National

Association of Insurance Commissioners. The letter, dated Aug. 5,

was posted on the FDIC website.

Disclosures reviewed by Dow Jones show the two largest life

insurers, MetLife Inc. (MET) and Prudential Financial Inc. (PRU),

currently tell beneficiaries their accounts are not FDIC-insured.

Prudential includes the information in a letter to beneficiaries,

while MetLife includes it in the first paragraph of its "customer

agreement" and in a brochure it sends to beneficiaries.

"Based on our Legal Counsel's initial review of sample

documentation from an insurance company to a beneficiary, we

believe that consumers may mistakenly conclude that the RAAs are

products offered by insured depository institutions and, further,

that the RAAs are FDIC-insured accounts," Bair's letter said.

Instead of the $250,000 guarantee that backs FDIC-insured bank

accounts, funds in insurers' retained-asset accounts are backed by

state insurance guaranty funds. They typically offer protection of

$300,000 or more.

Some critics of the accounts have questioned whether the state

guaranty funds would back the accounts if an insurer failed,

suggesting they could be considered separate from the insurer's

other obligations to policyholders.

But Peter Gallanis, the president of the National Organization

of Life and Health Insurance Guaranty Associations, said that

assertion was false. State guaranty funds, he said, have in fact

paid out on the accounts in the past.

He cited the failure of several companies run by financier

Martin Frankel that were taken over by state regulators in the late

1990s as an example. Frankel was sentenced to more than 16 years in

prison in 2004 after pleading guilty to 24 counts of fraud and

racketeering.

"They were treated just like a death benefit," Gallanis said of

the retained-asset accounts at insurance companies where Frankel

played a role. "For our record-keeping purposes, RAAs are

categorized as death benefit payments. There's no difference in our

eyes."

Still, the NAIC has announced its own review of what and how

insurers tell beneficiaries about the accounts, and plans a meeting

of a working group to examine the topic at the organization's

quarterly meeting in Seattle this weekend.

New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo is among the officials

who have said they are examining the accounts. He announced a

"major fraud investigation" last month, and said insurers are

pocketing "secret profits" by paying less in interest than they

make by investing the funds.

Insurers targeted by Cuomo, including MetLife and Prudential,

have said the accounts provide a valuable service to grieving

beneficiaries who need time before making decisions about what to

do with their payouts. The practice of offering the accounts dates

back more than two decades.

Edolphus Towns (D-N.Y.) also said this week that the House

Oversight and Government Reform Committee that he chairs is

investigating the payouts after he learned that Prudential does not

automatically deliver a lump-sum check to beneficiaries of deceased

soldiers. Prudential runs the government's life insurance programs

for soldiers and veterans.

Seperately, the head of the National Conference of Insurance

Legislators on Thursday proposed that states adopt a rule requiring

insurers to have beneficiaries opt in to the accounts instead of

making them the default option.

Insurers typically pay rates on the retained-asset accounts akin

to money-market accounts. Some guarantee minimums either when the

policies are sold or when they're redeemed, meaning some companies

currently have customers earning 3% or more, at a time when

money-markets are yielding far less.

-By Erik Holm, Dow Jones Newswires; 212-416-2892;

erik.holm@dowjones.com

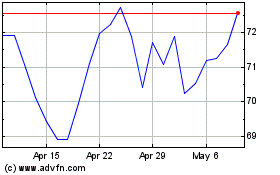

MetLife (NYSE:MET)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

MetLife (NYSE:MET)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024