By David Uberti

Months after a burst of optimism about the potential for

technology to help track the spread of Covid-19, a hodgepodge of

mobile phone apps around the U.S. has yielded unclear results amid

inconsistent policies and usage.

Ten states and Washington, D.C., have launched apps that notify

users of exposure to infected people through a development

framework built by Alphabet Inc.'s Google and Apple Inc. Eleven

more are either piloting or building such tools.

But the lack of a national strategy -- unlike in many European

countries that have adopted such apps -- adds a hurdle to making

sure the tools work across state lines as case counts tick upward,

tech and public health experts say.

"If you're going to have a lot of jurisdictional boundaries that

cut through this, it will naturally make the system less

effective," said Eric Rescorla, chief technology officer of Mozilla

Corp.'s Firefox web browser.

Advances in the Bluetooth-based Google-Apple system in recent

months have reduced the cost for states to opt in, and created a

central server to store anonymized markers of positive tests for

when phones cross state lines.

Some state governments also are collaborating to roll out tools

they see as a useful addition to a disease-fighting tool kit that

includes mask wearing, social distancing and traditional contact

tracing through phone calls and other manual outreach.

California, Oregon and Washington last month announced pilot

programs for apps on the Google-Apple system. Pennsylvania and

Delaware last month launched apps created by Irish developer

NearForm Ltd., which has built tools for several European

countries. New York and New Jersey unveiled NearForm-made apps this

month.

"You have a lot of cross-border travel," said Larry Schwartz,

who led New York's app push on the state's Covid-19 task force. "We

have people from New Jersey who work in New York, and vice

versa."

About 1.2 million people have downloaded the NearForm apps

across New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware, according

to the company and state officials.

In Delaware, about 10% of people who test positive in the state

report that they have downloaded its app, said Molly Magarik,

Department of Health and Social Services secretary. More than 80%

of those users say they accepted a six-digit code that verified

their test result and allowed their phone to send notifications to

other devices, she said.

Still, some public health experts remain skeptical that the apps

will push users to isolate or get tested.

"What evidence do we have that these make a difference?" said

James Thomas, a professor of epidemiology at the University of

North Carolina at Chapel Hill. "Is it a placebo for us to feel

better about what we're doing -- and feel like we have a high-tech

response -- or does it make a dent in the number of cases we're

seeing?"

In some cases, the lack of evidence is by design, said Joanna

Masel, a University of Arizona biology professor who is helping to

lead the state's app pilot program at her school and Northern

Arizona University. About 33,000 people have downloaded the app

around the university campuses, Ms. Masel said, and those who

tested positive for Covid-19 increasingly are entering verification

codes on the app. But she declined to provide specific numbers for

the latter metric.

"The reason we're not sharing information is we're really

concerned people will think it's not private," she said.

While some public health experts prefer Global Positioning

System data to aid traditional contact tracing, which tracks

people's interactions and movements, privacy experts warn it could

lead to surveillance.

The Arizona project relies on a blueprint unveiled by Google and

Apple in May using only Bluetooth-enabled alerts of users'

proximity rather than collecting GPS location data.

Apple last month rolled out an upgrade that allows iPhone users

in participating states, like Colorado, to opt into the network

without a dedicated app. The Association of Public Health

Laboratories, a trade group, also has partnered with the two

companies, as well as Microsoft Corp., to develop a central server

that stores anonymized verification codes for infected people

across the Google-Apple system. Eight states with statewide apps

and two with pilot programs have opted in so far, according to the

trade group's website.

Still, 27 states haven't launched an app or aren't actively

developing one, public health officials said. Many cited concerns

about utility, in addition to real or perceived privacy fears.

"There is much distrust around contact tracing as it is," said

Nancy Nydam, spokeswoman for the Georgia Department of Public

Health.

Attempts to use apps stalled in at least two states after they

launched GPS-based tools from local developers in the early months

of the crisis.

In April, South Dakota adopted the Care19 app built by a

developer best known for an app that connects North Dakota State

University football fans during the team's frequent national

championship runs. The state hasn't moved forward with a tool on

the Google-Apple system.

Similarly, in Utah, the Healthy Together app disabled its

location-tracking feature in July, said Jared Allgood, co-founder

of Twenty Holdings Inc., the app's developer. The company, which

previously built an app called Twenty marketed as a tool to help

"real friends" meet up in "real life," remains in talks with Google

and Apple to jump to their system, a spokeswoman said.

Healthy Together, which has more than 94,000 users in Utah, has

shifted away from trying to track the virus and toward surveying

symptoms and relaying test results, Mr. Allgood said.

"We were early," he added. "For everybody, it was their first

pandemic."

Write to David Uberti at david.uberti@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 21, 2020 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

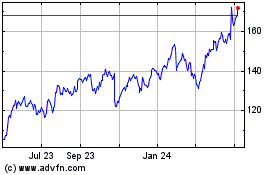

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

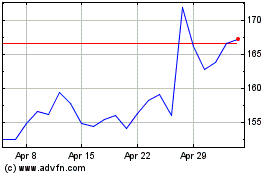

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024