By Jason Zweig

The best-performing stock of the past 30 years isn't Warren

Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway Inc., Microsoft Corp. or Apple Inc.

It's little-known Jack Henry & Associates Inc., which provides

technology to banks and other financial firms from its headquarters

in Monett, Mo. ( population 8,873).

Jack Henry's story is common among the " superstocks" with the

highest long-run returns. Once-tiny companies, often neglected by

professional investors for years, end up earning higher returns

than stocks that were far bigger and better-known.

Surprisingly, small investors may have a big edge over Wall

Street's giants in capturing these gains. That's because, to earn

such superior long-term results, you have to withstand

bone-cracking short-term downdrafts along the way -- something most

fund managers can't do.

That insight emerges from an analysis by Wilshire Associates for

David Salem, co-chairman of New Providence Asset Management L.P.,

an investment firm in New York.

If you'd invested $1,000 in Jack Henry stock at the closing

price on Sept. 30, 1989, you'd have had $2,763,000 as of this Sept.

30, according to the Wilshire data. The same $1,000 invested in

Berkshire Hathaway would have grown to $36,000; in the S&P 500,

$16,000. Those figures include reinvested dividends.

Earning that spectacular gain, however, would have taken almost

superhuman determination: From June 2001 through October 2002, Jack

Henry's shares fell 67%. Between October 1996 and August 1999, the

stock underperformed the S&P 500 by a cumulative 72 percentage

points.

The numbers are consistent: Among the top 10 stocks over the

past three decades, four -- Fair Isaac Corp., Kansas City Southern,

Best Buy Co. and Monster Beverage Corp. -- suffered interim

declines of at least 75%, according to Wilshire. To end up earning

hundreds of times your original investment, you would have had to

lose at least three-quarters of your money along the way.

Monster's stock dropped 92% from March 1990 through December

1995; the shares cumulatively underperformed the S&P 500 by 534

percentage points between late 1990 and early 2000, according to

Wilshire. Yet $1,000 invested in Monster's stock three decades ago

grew to $506,000 by this past Sept. 30.

Surely only a professional investor can withstand that kind of

pain? Au contraire, says Mr. Salem: "It's potentially career-ending

for a manager to hold such big interim losers. I wonder if any

manager has ever been able to stay the entire course with stocks

like these."

A dirty secret of the investment business is that fund managers

don't buy and hold -- not because they don't want to, but because

they can't.

That isn't just because clients would fire them for holding on

to losers.

The more successful a little company is, the faster it becomes

midsize and then large. Consider Amazon.com Inc. It went public in

1997 with a market value of about $300 million, qualifying it as a

small company. Less than three years later, the stock had a market

value of nearly $13 billion.

Small-company mutual funds that owned Amazon when it was tiny

had to sell it once its market value grew into the billions.

Otherwise it would have dominated their portfolios. Investors in

those funds missed out on nearly all of Amazon's stratospheric

growth.

Small stocks earn their highest returns not when they are small

but rather as they migrate to large, according to research by

finance professors Eugene Fama and Kenneth French.

That description fits Jack Henry to a T.

Founded in 1976, the company first sold shares to the public in

November 1985. As of 1996, insiders still owned 41% of the stock;

not until 2006 did any institutional investor show up owning 5% or

more of the shares. Only in November 2018 did Jack Henry finally

grow large enough to join the S&P 500 index, where it currently

ranks 402nd by size.

The stock is no longer cheap -- it trades at a steep 41 times

the past 12 months' earnings and eight times book value, according

to FactSet -- but Jack Henry doesn't ride many market fads. "Most

of our growth has been truly organic," coming from business

expansion rather than acquisitions, says finance chief Kevin

Williams.

Unlike a lot of larger companies, Jack Henry hasn't borrowed

money to finance massive buybacks of its own stock; it has no

long-term debt. On the back of the company's business cards is the

founders' original motto: "Do the Right Thing, Do Whatever It

Takes, Have Fun."

Today, 94% of Jack Henry's stock is held by institutions, but

it's unlikely any single fund manager has held the shares

continuously for the whole wild ride.

Who could? For all the talk about how individual investors have

faded as a market force, results like Jack Henry's are a reminder

that no other constituency is in a better position to buy and

hold...and hold...and hold.

No one can fire you for hanging onto a stock that loses 75% or

more; you are free to seek value in the most obscure companies or

to find hope in the darkest hour.

In 1974, the financial analyst Benjamin Graham said: "I am

convinced that an individual investor with sound principles, and

soundly advised, can do distinctly better over the long pull than a

large institution."

He was right then, and his words may be even truer today.

Write to Jason Zweig at intelligentinvestor@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 13, 2019 11:14 ET (16:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

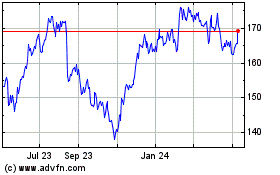

Jack Henry and Associates (NASDAQ:JKHY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

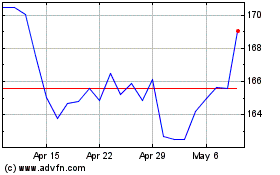

Jack Henry and Associates (NASDAQ:JKHY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024