Fannie and Freddie's Uncertain Future, Explained

April 24 2019 - 11:29AM

Dow Jones News

By Christina Rexrode and Heather Seidel

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are the heart of the U.S. housing

system.

They're also a topic of intense debate.

The Trump administration recently asked for plans to overhaul

Fannie and Freddie. It also installed a new official to oversee the

two companies, and he says he wants to put them on the road toward

returning to private hands. Yet lawmakers have spent the last

decade arguing about how big they should be and how much the

government should be involved in their operations. Some have said

they shouldn't exist at all.

So what's the hangup?

Fannie and Freddie make mortgages more readily available and

more affordable. The 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage essentially owes

its existence to them. But some argue that the private market could

fill this role more efficiently. Right now, there isn't much

agreement on either side of the aisle on how to change the

government's involvement in mortgages or what the market would look

like without the two companies.

The government created Fannie in response to the Great

Depression to encourage banks to make more home loans. Fannie and

Freddie buy mortgages from banks, alleviating some of the risk that

lenders have to take on.

Almost half of mortgages made today are backed by Fannie and

Freddie.

Critics of this system say the private sector, not the

government, should be filling this role, and the White House has

said it wants more competition. Private firms make up just a tiny

portion of this market now.

Those who support the current setup point out that private firms

tend to exit whenever a market starts to turn sour. That means

credit can dry up at a time when the economy is already struggling,

making a downturn worse.

Supporters also say the government has a responsibility to keep

housing affordable. For many Americans, owning a home has been the

most important way to build wealth.

This is how the two companies work:

Why is this process so important?

Banks are wary of making mortgages they have to keep on their

books. For one reason, they're then on the hook if a borrower stops

paying.

Banks are also worried about interest rates rising and falling.

Say a lender gives you a mortgage with a 4% fixed interest rate,

and then rates rise. The bank can't then increase the rate on your

mortgage. That's good for you but bad for the bank, which is now

holding a mortgage that is less valuable.

But lenders aren't so concerned about these risks if they sell

the mortgages.

If lenders couldn't sell their mortgages, they would probably

make fewer of them, charge higher interest rates and require bigger

down payments.

That means that without Fannie and Freddie, few lenders likely

would offer the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage.

This product is practically considered an American birthright.

But in other countries, where mortgage systems are funded

differently, the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage isn't widely

available.

Mortgages in the U.S. were also much different before Fannie was

created. Back then, mortgage loans often had floating rates and

typically lasted for just five or 10 years, with a big balloon

payment that came due at the end.

Some economists argue that allowing mortgage rates to fluctuate

with the broader market would help borrowers. Rates tend to fall in

a recession, which would give home buyers a discount on their

monthly payment when they most need it.

But Americans tend to like the certainty of fixed rates. Even a

1-point change in your mortgage's interest rate can add -- or

subtract -- hundreds of dollars from your monthly payment.

U.S. borrowers flocked to adjustable-rate mortgages in the

run-up to the financial crisis, but they returned to the 30-year,

fixed-rate loan after the housing bubble burst in 2008. Today, more

than 90% of U.S. home buyers choose this product.

Write to Christina Rexrode at christina.rexrode@wsj.com and

Heather Seidel at heather.seidel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 24, 2019 11:14 ET (15:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

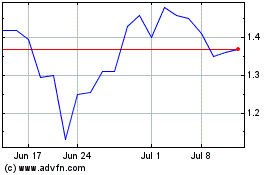

Fannie Mae (QB) (USOTC:FNMA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

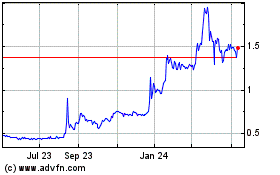

Fannie Mae (QB) (USOTC:FNMA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024