By Ben Fritz

A federal judge's verdict this coming week on whether AT&T

Inc. can acquire Time Warner Inc. will shape a much broader drama:

a radical reordering of the entertainment business that's reaching

every corner of Hollywood.

Technology giants are rapidly devouring a media industry that

has long been dominated by the same group of entertainment

companies -- storied Hollywood studios, television networks and

cable giants. Now, many of those incumbents are scrambling to

transform themselves so that they can stand up to the powerful

invaders from Northern California.

"I've never seen this much uncertainty and insecurity in the

legacy entertainment businesses before," said Bruce Berman, a

veteran studio executive who heads Village Roadshow Pictures.

Netflix Inc. is leading the charge. The company has 131 million

subscribers world-wide, drawn to its massive array of programming

available to watch anytime and anywhere. But the true threat it

poses to traditional media firms is behind the scenes. It is this

year streaming about 700 pieces of original content -- television

series, movies, stand-up specials and more -- to consumers with

whom it has direct relationships, making it a new type of media

superpower possible only in the digital age.

Its success, along with similar looming threats from tech giants

like Amazon.com Inc. and Apple Inc., are leading other major media

players to press for the scale and breadth necessary to remain

relevant.

If AT&T's purchase of Time Warner goes ahead as planned, it

would combine a wireless-data giant with the parent of

premium-cable powerhouse HBO, film and television studio Warner

Bros. and cable networks like TNT and CNN.

Next in line is Walt Disney Co.'s $53 billion agreement to buy

most of the assets of 21st Century Fox Inc., intended to create an

entertainment behemoth big enough to launch new digital businesses

that could compete with Netflix -- unless Comcast Corp. snags the

deal with its own competing offer for the assets. (21st Century Fox

and Wall Street Journal-parent News Corp share common

ownership.)

CBS Corp and Viacom Inc. have held on-and-off talks about

combining, complicated by clashes between CBS's management and the

two companies' common owner.

Practically every other major Hollywood company has spent the

past year more quietly considering potential purchases, sales or

mergers, according to people close to them.

Sony Pictures Entertainment is often named as a potential

acquisition target, but the Japanese-owned studio isn't currently

for sale, its top executives have said. That's in part because its

management is attempting to improve its previously weak performance

and increase its value to be in a stronger position as a buyer or

seller, a person close to the studio added. Sony has considered

going after Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc., an independent studio that

bought the pay-cable channel Epix last year, the person said.

MGM has also long been a target of Lions Gate Entertainment

Corp. Lions Gate, meanwhile, in 2016 acquired pay cable channel

Starz and recently bought majority control of a large talent

management and TV production company, 3 Arts Entertainment.

In some cases, media companies are also seeking more global

exposure in these deals -- something Netflix already has in

virtually every country except China. And then there's the pressure

to compete against digital powerhouses Facebook Inc. and Alphabet

Inc.'s Google, which are gobbling up the market for advertising

dollars.

Buying and selling companies has long been standard in

Hollywood, where deep-pocketed investors sought to capitalize on

celebrity glamour and would-be disruptors arrived looking to

develop new synergies. Universal Studios has had five owners over

the past 30 years. And Sony Corp.'s acquisition of Columbia

Pictures in 1989 and America Online's purchase in 2000 of Time

Warner -- itself the product of years of deal making -- are both

remembered as among the most misguided tie-ups in corporate

history.

This time, however, virtually all the deals in progress are a

reaction to one catalyst -- a seismic shift in the media business

that has been driven primarily by Netflix.

From its early days in the late 1990s and 2000s as a distributor

of DVDs and then, starting in 2007, as a streamer of old movies and

television shows, Netflix was a lucrative source of income for the

traditional Hollywood companies from which it bought content. It

was right on the cutting edge of changing consumer behavior,

offering value-conscious and digital-savvy consumers exactly what

they wanted: unlimited viewing on-demand for a flat monthly

fee.

In 2013, Netflix produced its first original series, "House of

Cards," and started to become a competitor to the very networks and

studios from which it had been buying content. Now, just five years

later, the company says it spends close to $8 billion producing and

licensing content. Some analysts calculate the company's content

expenditures differently and peg the number even higher. The

streaming giant last year spent more than any other media company

producing and licensing nonsports content, according to media

analysts at Bernstein Research.

Hollywood was able to coexist with Netflix as the biggest online

distributor of movies and TV shows so long as Netflix was also the

biggest buyer. But now, it's a major producer in numerous

categories, from dramas to comedy to reality shows to stand-up

specials to feature films. It is signing exclusive deals with top

talent like "Scandal" creator Shonda Rhimes, who was previously

affiliated with ABC. Netflix doesn't need anyone else in Hollywood

to function, and consumers may not need any other provider to get

their total entertainment fix.

Amazon hasn't been as successful as Netflix, but it recently

hired a new entertainment chief and is determined to make its Prime

Video service, with an annual budget of nearly $5 billion, a

powerhouse in entertainment. It recently agreed to pay hundreds of

millions for the rights to make a "Lord of the Rings" TV series,

people with knowledge of the deal said. This past week, Amazon

signed a deal with Jordan Peele, the producer and director of the

hit movie "Get Out" that will give the company a first look at

potential series from him. Apple is also making deals for TV shows

from top talent like actress Reese Witherspoon and is committed to

spend $1 billion just to get started.

Some legacy studios are moving to lock down their talent. Time

Warner's Warner Bros. this past week signed a $300 million,

long-term agreement with Greg Berlanti to keep the prolific TV

producer in its stable.

"It's a message not only to our creative community but the

creative community at large," Kevin Tsujihara, chief executive of

Warner Bros., said of keeping Mr. Berlanti's services amid the

talent wars fueled by Netflix.

Netflix recently surpassed Disney and Comcast in market

capitalization, while Amazon and Apple each have bigger market caps

than every major media company combined.

And because media is not a core business for Amazon and Apple,

both can spend freely without worrying as much about profits as

studios and networks whose existence they threaten.

The nightmare scenario for incumbent studios is one in which a

handful of giants that fuse digital distribution with massive

production essentially own media. This would be a landscape in

which all movies and TV shows were made and distributed on

direct-to-consumer digital platforms owned by Netflix, Amazon,

Apple, Comcast, AT&T-Time Warner or Disney-Fox. Because each of

those companies would have such massive resources and diverse

operations, they wouldn't need partners to prosper. Everyone left

over in Hollywood would either get swallowed or wither.

The storied William Morris Agency is one example of how

Hollywood giants are pivoting to avoid this fate. For more than a

century, the agency had a simple role in Hollywood: It represented

the creative talent, cutting deals for writers, directors or actors

in exchange for a percentage of their income. But in today's

entertainment business, companies that do only one thing are

unlikely to have the scale to survive.

So William Morris, which merged with rival agency Endeavor in

2009, has been on an expansion tear. The company, now known as

William Morris Endeavor Entertainment, has snapped up companies in

adjacent businesses including sports, fashion, live events and

mixed-martial-arts fighting.

Late last year it quietly launched Endeavor Content, a new

sibling company that invests directly in films and TV shows. It

helped fund the TV series "Killing Eve," a hit that aired on BBC

America, and the recent film "Book Club," starring starring Diane

Keaton and Jane Fonda, a modest success released by Paramount

Pictures.

Endeavor Content is attempting to help the talent the agency

represents and others produce content outside of those massive

tech-media silos. "Everything we're doing is geared toward helping

to empower creators in a disrupted landscape," said Graham Taylor,

co-president of the business.

When creators can sell near-finished products, financed with

independent money, to technology and media giants, they're more

likely to get better deals, Mr. Taylor said. It also makes it more

difficult for tech-media behemoths to get the content they want

without partnering with Endeavor.

The decision expected June 12 on the AT&T-Time Warner merger

will be a key test for the entertainment industry.

The Justice Department is trying to derail the merger, arguing

that the combination of the telecommunications and pay-TV

distribution giant with one of the biggest producers of

entertainment content would be anti-competitive and harmful to

consumers.

A combined AT&T-Time Warner, the Justice Department has

argued, would have the leverage to force other pay-TV providers to

pay higher prices for Time Warner-owned channels such as TNT and

CNN. Those costs would then be passed on to consumers.

AT&T and Time Warner have countered that it has no incentive

to withhold content from rival providers and that such scale is

necessary to compete against Silicon Valley tech giants.

If the court puts a hold on the AT&T-Time Warner deal, the

manic race to expand and to consolidate might slow down.

But many expect that the deal will go through in some form, and

the frenzy will continue.

Says Mr. Berman, the studio executive: "The AT&T case is not

just looming over Time Warner, but looming over the whole future of

the media landscape."

--Joe Flint contributed to this article.

Write to Ben Fritz at ben.fritz@wsj.com

Refer text goes here blah blah on this page B00

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 08, 2018 12:40 ET (16:40 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

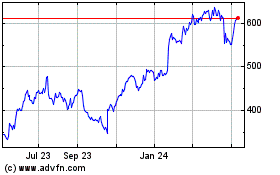

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

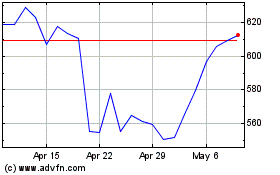

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024