QUERÉ TARO, Mexico—Jody Fledderman is one of five original

employees at the auto-parts factory his father founded in rural

Batesville, Ind. He also spends a lot of time at the company's

97,000-square-foot plant in central Mexico.

The two operations have expanded together as automotive

production in both countries boomed. Mr. Fledderman credits the

success of Batesville Tool & Die Inc., where he is president,

in part to the addition of a Mexican plant 16 years ago that helps

service Honda Motor Co., Nissan Motor Co. and other clients on both

sides of the border.

"We have three or four clients back in Indiana that we wouldn't

have had if we weren't here," Mr. Fledderman, 54 years old, said in

an interview at the plant in Queré taro.

President-elect Donald Trump has said that in his first days in

office he will reopen talks on the North American Free Trade

Agreement, which connects Canada, the U.S. and Mexico, and leave

the pact if Mexico doesn't agree to improved terms for the U.S. He

blames unfair trade, in particular with Mexico and China, for the

loss of millions of factory jobs.

Ending the 1994 trade pact is relatively easy. The U.S. legally

can pull out of Nafta six months after Mr. Trump as president

notifies Mexico and Canada of his intention to do so, according to

a September study by the Peterson Institute for International

Economics in Washington. Imposing tariffs on imports lies within

the authority of U.S. presidents.

For the auto industry, as Mr. Fledderman's business shows, such

a change would be substantially more complicated, because of the

multilayered connections between U.S. and foreign suppliers and

assembly points. The tens of thousands of parts that make up any

vehicle often come from multiple producers in different countries

and travel back and forth across borders several times.

This is a tenet of modern manufacturing: Where a product is

ultimately assembled increasingly has little bearing on where its

component parts are made.

Assembly plants are prized engines of a local economies because

they tend to pay better than most factories. Mr. Trump has

repeatedly criticized Ford Motor Co.'s plan to move assembly of its

Focus compact from Wayne, Mich., to Mexico, vowing to impose a

steep tariff on the car if Ford follows through. Ford executives

have said moving the Focus to Mexico won't result in American job

losses and that the company remains committed to producing in the

U.S.

But more than half the parts in the Focus today are made outside

the U.S. and Canada, including 20% in Mexico. Ford also ships in

some of the car's engines from Spain and transmissions from

Germany.

Similarly, only 10% of the parts that go into the 200,000 BMW

luxury crossovers built each year in Spartanburg, S.C., come from

U.S. and Canadian plants, according to U.S. government data. The

rest are imported from Europe and elsewhere. BMW in turn exports

most of the Spartanburg plant's production around the world.

By contrast, 70% of the components in the Honda CR-Vs assembled

in Guadalajara, Mexico—the production of which soon will be moved

to central Indiana—are currently made by U.S. and Canada-based

factories, data show.

The parts that make up a car or truck, from bolts to motor

blocks, window lifts to oil filters, account for two-thirds of its

value, according to the Motor & Equipment Manufacturers

Association, a trade group.

U.S. assembly plants vary on the amount of U.S.-made components

they use. A Chevy Silverado pickup built in Indiana has 51% parts

content from Mexico, according to the window sticker, while Ford's

exclusively U.S.-assembled F-Series truck, the country's top

selling vehicle for 39 years straight, has 70% U.S. and Canadian

content.

"This industry, particularly in North America, has integrated a

lot," said Thomas Klier, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank

of Chicago who specializes on automotive supply chains.

Such integration poses a challenge for anyone wanting to buy an

entirely U.S.-made vehicle.

"You can't buy an American-made car anymore. You can buy an

American-assembled car," said Loren Baisden, 32, a 13-year veteran

of Ford's assembly line now working at the company's heavy-truck

chassis plant in Avon Lake, Ohio.

Auto makers and many primary suppliers have moved some high-tech

production to Mexico and elsewhere. Lower-tier suppliers typically

relegate labor-intensive production such as assembling wire

harnesses or sewing materials for seats to low-wage Mexico plants

while keeping more highly skilled and automated tasks at their U.S.

factories.

That strategy allows auto makers and their suppliers to be cost

competitive with Asian and European imports, analysts say.

"The free flow of components is integral to the supply chain in

auto manufacturing," Steve Arthur, an automotive analyst at RBC

Capital Markets, said Thursday. It is "a situation not easily or

inexpensively reversed."

Still, with so much final assembly moving to Mexico, the

epicenter of North American auto production, which for more than a

century has been deeply rooted in the Midwest, is moving an average

of 14 miles toward the Southwest annually, according to a 2014

analysis by IHS Markit Automotive Advisory, the consultancy.

The neighboring small Indiana cities of Anderson and Muncie,

which straddle Interstate 69 less than hour's drive north of

Indianapolis, have been suffering that migration for more than

three decades, as General Motors Co. and its suppliers have

decamped for the south. The cities collectively have lost tens of

thousands of high paying factory jobs.

Mursix Corp., a family-owned supplier company on the edge of

Muncie, has been under increasing pressure to move some operations

to Mexico to be closer to big Japanese and U.S. firms located

there. The maker of switches, connectors and other electronic

components exports about 60% of what it produces, primarily to

Mexico, company president Todd Murray said.

The company is losing two product lines to suppliers located

near his customers' Mexico plants, he said.

"That scares me," said Mr. Murray, 47, whose company opened a

plant in China 11 years ago to win business there. "I see that

[competition] becoming more aggressive in the years to come."

Mr. Murray said Wednesday that if a Trump administration

overhauls or scraps Nafta, and gets tough with China, it could

ultimately help him fend off that competition.

In the short run, he said, the healthier operating margins

available to companies producing in Mexico will outweigh any new

U.S. import duties. With the right policy mix, including lower

corporate taxes, Mr. Murray said, any profits from Mexico

operations could be invested to create cutting-edge technology jobs

in the U.S.

U.S. and Canada-based factories shipped nearly $29 billion worth

of parts to Mexico in 2015, according to INA, the Mexican

auto-parts industry's national association. Mexican plants in turn

sent more than $61 billion worth of parts to the two Nafta

partners, accounting for much of the trade surplus Mexico has with

the U.S.

About a third of Mexico's 1,300 suppliers, which employ some

720,000 people, are U.S. owned, according INA. Mexican, Asian and

European companies make up a growing share of U.S.-based suppliers,

which the U.S. Labor Department says provide jobs for nearly

600,000 Americans.

Mr. Fledderman's Batesville Tool & Die produces an array of

components for the automotive, appliance and other supply chains.

The 38-year-old company is a primary supplier to Honda and makes

parts for Swedish air bag maker Autoliv AB, currently its biggest

Mexico customer.

Some components, including engine hood hinges, oil filter seals

and air bag parts, are made on both sides of the border to be

closer to customers who demand quick and reliable delivery of

parts.

The plant in Batesville, a town of 6,000 staked amid the corn

and soy fields of hilly southern Indiana, also handles product

design and employs robots and a 3-D printer to make more intricate

or larger parts. The Batesville factory has expanded five times in

recent years as the company's North American business has surged.

The company now employs 800 people, evenly divided between its two

factories, and has annual revenue of $130 million, up from $8

million in 1989, when Mr. Fledderman took over.

"You don't make any money producing things that everybody in

every corner of the world can make," said Mr. Fledderman, who

recently returned to Indiana from his latest tour of Eastern

Europe, where he sniffed out opportunities. "If it's not Mexico,

then it's Poland or Vietnam or wherever. We're not the low-cost

country in the world."

Auto production in Mexico by U.S., Asian and European auto

makers has boomed in the past decade, nearly doubling to reach 3.4

million light vehicles last year.

Despite the surge in Mexico, nearly 60% of the 17.5 million

light vehicles sold in the U.S. last year were assembled within a

so-called auto alley that runs from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of

Mexico, said James Rubenstein, a geographer at Miami University of

Ohio who writes extensively about the industry.

Imports from Nafta partners Mexico and Canada, which contain a

heavy mix of North American made parts, account for much of the

rest. The auto-parts industry alone accounted for about 14% of the

$531 billion in U.S.-Mexico trade in 2015, according to U.S.

government data.

"In this day and age, when so much manufacturing has left the

U.S., the auto industry is a striking exception," Mr. Rubenstein

said. "It's not a win-lose situation. It's dividing up the growth.

Mexico is winning, but so is auto alley."

In Anderson, Ind., a business incubator and economic development

project known as the Flagship Enterprise Center—a joint effort by

the city government and Anderson University financed in part with

federal grants—tries to attract industrial investment and to foster

development of advanced technology, such as electric automotive

engines.

"There was a realization that no one was coming to pull us out

of the deep water. We got together and started pulling ourselves

up," said Charles Staley, 70, a former senior engineer at GM's

defunct Delco-Remy subsidiary in Anderson, who now heads the

enterprise center. "Today, it's stable," he said of the local

economy. "We're growing. We're expanding."

So far, 17 foreign companies, including Swiss foods giant Nestlé

SA and NTN Corp., the Japanese drive shaft maker, have located

plants in the city, only a few them tied to the automotive

industry. Purdue University, which has one of the largest U.S.

engineering programs, plans to open a polytechnic campus next

spring on land where a GM plant once stood.

"Have we replaced all the jobs we lost? No. But we've got the

first 5,000 or 6,000 in," said Greg Winkler, Anderson's director of

economic development. "What we're doing now is finding a way to

reintegrate this city into the global conversation."

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 10, 2016 13:45 ET (18:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

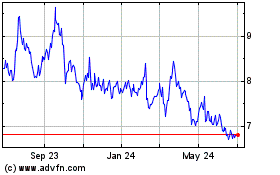

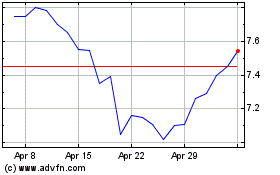

Nissan Motor (PK) (USOTC:NSANY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Oct 2024 to Nov 2024

Nissan Motor (PK) (USOTC:NSANY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2023 to Nov 2024