By Sam Schechner and Emily Glazer

A European Union privacy regulator has sent Facebook Inc. a

preliminary order to suspend data transfers to the U.S. about its

EU users, according to people familiar with the matter, an

operational and legal challenge for the company that could set a

precedent for other tech giants.

The preliminary order, the people said, was sent by Ireland's

Data Protection Commission to Facebook late last month, asking for

the company's response. It's the first significant step EU

regulators have taken to enforce a July ruling about data transfers

from the bloc's top court. That ruling restricted how companies

like Facebook can send personal information about Europeans to U.S.

soil, because it found that Europeans have no effective way to

challenge American government surveillance.

To comply with Ireland's preliminary order, Facebook would

likely have to re-engineer its service to silo off most data it

collects from European users, or stop serving them entirely, at

least temporarily. If it fails to comply with an order, Ireland's

data commission has the power to fine Facebook up to 4% of its

annual revenue, or $2.8 billion.

Nick Clegg, Facebook's top policy and communications executive,

confirmed that Ireland's privacy regulator has suggested, as part

of an inquiry, that Facebook can no longer in practice conduct

EU-U.S. data transfers using a widely used type of contract.

"A lack of safe, secure and legal international data transfers

would damage the economy and prevent the emergence of data-driven

businesses from the EU, just as we seek a recovery from Covid-19,"

Mr. Clegg said.

Ireland's Data Protection Commission declined to comment.

The preliminary order is a victory for European privacy

activists, who have been arguing before regulators and in court for

the better part of a decade that their data shouldn't be sent to or

kept in the U.S. because it could be turned over to the government

under secret requests.

It is also a warning for big tech companies with operations in

Europe, and for the trans-Atlantic trade they facilitate. Though

the order applies to Facebook, the company may be the first in the

queue in front of other U.S.-based tech companies to face similar

orders, one of the people familiar with the matter said. At stake

is whether the U.S. might have to change its surveillance laws for

data transfers to resume, the person added.

Blocking big tech companies' data transfers to the U.S. could

upend billions of dollars of trade from cross-border data

activities, including cloud services, human resources and

marketing, because they involve accessing or storing information

about Europeans from U.S. soil, tech advocates say. Similar logic

could also be used to block transfers to other countries with

surveillance laws deemed invasive by EU courts, advocates add.

To be sure, Ireland's order is preliminary and could be revised

before it is finalized, a process that could take several months.

Ireland's data commission leads EU privacy enforcement for Facebook

because it has its regional headquarters in the country, but

Ireland's privacy regulator must coordinate with counterparts in

other EU countries in cross-border cases.

Ireland's data commission has given Facebook until mid-September

to respond to the order, the people familiar with the matter said.

After considering Facebook's responses, the data commission told

the company it plans to send a new draft of the order to the 26

privacy regulators in other EU countries for joint approval under a

cooperation provision of the bloc's privacy law, the people

added.

Facebook could also potentially challenge the order in court.

Internally, Facebook considers the preliminary order and its future

implications a big deal, one of the people said. Because of its

sensitivity, the existence of the order is being held closely

inside Facebook while executives and lawyers determine how to

respond, that person and another person familiar with the matter

said.

Since the July ruling, the European Commission, the EU's

executive arm, and U.S. officials have started negotiations to

establish a new way for companies to send data on Europeans to the

U.S. that would comply with the court's requirements. But "there

will be no quick fix," EU Justice Commissioner Didier Reynders said

in European Parliament last week.

Some privacy lawyers have said that the U.S. would need to

change its surveillance laws to address the court's concerns. The

U.S. for its part has said that its surveillance practices are

proportionate, and in court argued that the EU shouldn't exercise

jurisdiction over U.S. national security practices.

The focus now is on EU's privacy regulators to see how they

enforce the July ruling. A board representing EU privacy regulators

last week announced a task force to tackle the topic. Ireland's

data commission has been closely watched because, in addition to

Facebook, it also leads EU privacy enforcement for several big tech

companies, including Alphabet Inc.'s Google, Apple Inc. and Twitter

Inc.

Ireland's plan to order Facebook to stop sending data to the

U.S. -- even if only preliminary -- marks a major shift in more

than two decades of wrangling between the EU and U.S. over how to

balance privacy and commerce when it comes to trans-Atlantic data

flows. In 2015, the EU's top court invalidated a major legal

mechanism for transferring such information to the U.S. But the

threat ended up being mostly theoretical: No company actually faced

a specific order to stop sending personal information, and the data

flows never stopped.

At issue is a basic precept of EU privacy law dating back to the

1990s. It is illegal for a company to send personal information

about EU residents to another part of the world that doesn't offer

essentially equivalent privacy protections to the EU -- except in

certain circumscribed circumstances. The U.S., which doesn't have a

national data-privacy law but rather more sector specific

regulations in some areas, such as health care, didn't make the EU

cut.

To keep data flowing, the U.S. and EU in the late 1990s

negotiated a special system, called Safe Harbor, where companies

sending European data to the U.S. could opt into EU-style rules,

enforced by the U.S. government. Companies also had other options

to send data overseas, such as using preapproved EU contractual

language, called standard contractual clauses, in which companies

promise to uphold European privacy standards.

Legal challenges to those systems began in 2013, after former

National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden leaked details

of U.S. government surveillance practices. A privacy activist named

Max Schrems argued that Safe Harbor exposed his Facebook

information to the U.S. government. The EU's Court of Justice

agreed, and struck down the system in 2015.

The EU and U.S. quickly worked out a replacement framework,

dubbed Privacy Shield, which added some additional protections such

as an ombudsperson at the U.S. State Department to field complaints

from Europeans. But July's Court of Justice decision struck that

system down, too, saying that the U.S. still didn't provide

Europeans with actionable rights to challenge surveillance.

Businesses were initially comforted that the July decision

stopped short of invalidating the so-called standard contractual

clauses as well, and instead said that companies must assess

whether the laws of the countries where they are sending data allow

them to ensure adequate protection under EU law. Facebook was among

several companies that said over the summer that they would rely on

those standard contractual clauses to transfer data to the U.S.,

now that Privacy Shield was no longer valid.

But Ireland's sending of the preliminary order to suspend data

transfers suggests that it found such standard clauses aren't

sufficient under the ruling, at least in Facebook's case. If that

reasoning stands, such clauses might also be ruled invalid for

other large technology and telecommunications companies that, like

Facebook, fall under the purview of the U.S. surveillance laws

discussed in the EU court ruling, including Section 702 of the

Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

Noyb, a privacy advocacy group founded by Mr. Schrems, used that

reasoning in August when it filed privacy complaints to various EU

privacy regulators against 101 European websites, using the EU

court ruling to argue that they must stop sending data using

U.S.-based tech providers.

The potential that Facebook and other large tech companies might

have to stop sending data to the U.S. raises the stakes on efforts

to come up with replacement frameworks to allow such transfers. In

addition to talks with the U.S. to replace Privacy Shield with a

new system, the European Commission says it is also updating the

language of the standard contractual clauses. But it isn't clear

how such updates would address the court's surveillance

concerns.

Write to Sam Schechner at sam.schechner@wsj.com and Emily Glazer

at emily.glazer@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 09, 2020 13:34 ET (17:34 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

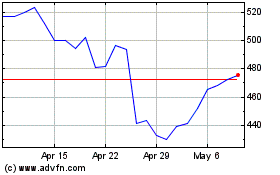

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024