By Michelle Ma

Capitol Hill has put Silicon Valley under the microscope.

With U.S. intelligence agencies continuing to raise concerns

about foreign meddling in U.S. elections through online social

platforms, technology executives have been called to account. In

September, Facebook Inc. Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg

and Twitter Inc. Chief Executive Jack Dorsey testified at a Senate

hearing on what their companies were doing in response to foreign

trolls and bots ahead of the November midterm elections. Regulators

and consumer-advocacy groups have also raised concerns about the

responsibility of large tech companies like Google Inc. to protect

the vast amounts of user data they hold.

To assess the impact technology is having on our political

systems, as well as what responsibilities private companies have to

their users and the greater public, The Wall Street Journal turned

to Nuala O'Connor, president and chief executive of the Center for

Democracy and Technology and the former chief privacy officer in

the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, and Beth Simone Noveck,

director of the Governance Lab and professor in technology, culture

and society at New York University's Tandon School of Engineering.

Prof. Noveck previously served as the U.S. deputy chief technology

officer in the Obama administration.

Edited excerpts follow.

A golden age?

WSJ: What do you think is the biggest threat that technology

poses to our democracy today? What do you view as its greatest

contribution?

MS. O'CONNOR: Its greatest contribution is also its greatest

threat. The greatest thing the internet has done is to allow for

the elevation of the individual voice: the dissident, the

stay-at-home mom, whichever person who wasn't formerly heard in the

public square. Yet because everything is now on the same playing

field, hate speech is on the same level in your daily life. As

industrial companies had a duty of care to clean up and to not harm

the environment, what is the duty of care that internet companies

have to not pollute the informational or social environments of the

communities they're serving?

PROF. NOVECK: The greatest contribution of technology is

simplifying, streamlining and automating the delivery of services

to people. The other contribution is turning our preferences into

new laws and new articulations of public will. There are lots of

ways we're seeing that beginning to happen, primarily outside of

the U.S. In Taiwan, for example, they've crafted 26 pieces of

legislation in the last few years on things like telemedicine or

the regulation of Uber that they've done with 200,000 members of

the public participating in those conversations.

One threat that comes with technology is the failure to use it

in the first place. The second is badly designed tech, or poorly

designed processes that create frustration for users.

WSJ: Do you believe social networks are ultimately helping

democracy or interfering with the democratic process?

MS. O'CONNOR: There has been harm done. Long term, I believe in

the ability of companies and the government to work together, if

they share a common goal to protect institutions and democracy. The

challenge will be to move quickly enough to combat real threats

that are out there.

PROF. NOVECK: Having much better access to information on the

whole is a plus for democracy. I think it's actually going to be a

golden age for active citizenship and engaged democracy. And as

difficult as some of the challenges that we have faced politically

are, we're getting people engaged, excited and talking to one

another.

WSJ: When it comes to hacks, user privacy and data exposures,

how much responsibility should tech companies take, and should

governments get involved?

MS. O'CONNOR: We've always believed that companies that were

trafficking or collecting data have a duty of care to keep your

data secure and to use it only for the purposes essential to the

transaction. We're supporting bills on Capitol Hill and actually

helping draft things around data portability, data deletion and

fundamental respect for your ongoing rights in your own data.

PROF. NOVECK: Everybody has a responsibility in this space,

including individuals to do things like change passwords and be

critical users of media in evaluating what we read. But this isn't

a one-sector solution. We should have those mechanisms, including

the reporting solutions, convening solutions and places for

companies to share perceived threats, and then solutions to these

problems.

WSJ: What can social-media companies do better to ensure that

democracy isn't compromised? To what extent should the government

be involved to ensure that the private sector doesn't interfere

with the democratic process?

MS. O'CONNOR: Simple top-level things like seeing where the IP

addresses are coming from and where the attack's actors are coming

from. I think there is a growing awareness that is clearly too late

for 2016, but hopefully not too late for 2020.

PROF. NOVECK: It is the responsibility of tech companies to

monitor. We increasingly have the tools, thanks to big data and the

ability to create predictive analytic tools, that will tell us,

"This is clearly a red flag because this is all coming from the

same place." We also need to modernize our election infrastructure,

especially how our courts handle these issues after the fact, and

the speed, response and availability to bring challenges to,

investigate and audit what happens in elections. The legal system

has to be prepared just as much as Twitter, Facebook, Amazon and

all these large-scale tech platforms.

Censorship

WSJ: Where do you draw the line between hate speech and

censorship? Do you think it's the responsibility of tech companies

to regulate how their users interact on their platforms?

MS. O'CONNOR: I'm still deeply concerned about state-mandated

company censorship, because we don't elect executives of

private-sector companies the way we do our government. So there

isn't accountability for their decisions. If you think there's a

risk that you're going to be fined by a government, I think the

tilt would be toward more takedowns, potentially incorrect

takedowns or over-censorship of marginalized groups such as people

of color, immigrants and non-English speakers. We've already seen

an overcorrection in some places. On the other hand, I think there

are some really thoughtful smaller platforms. The gaming platform

Twitch, for example, is self-monitoring in a collaborative way to

create a positive environment policed by the community itself.

PROF. NOVECK: When I worked in the White House back in 2009, one

of the first things that we did was to create a WordPress blog with

comments on the White House website. We were able to adapt

WordPress plugins to allow the users themselves to move off-topic,

offensive or spam to a different place. We took inspiration from a

lot of private companies like Reddit and Slashdot that have used

community self-moderation for a long time, to avoid being in the

position of being deemed responsible for the content on the

site.

WSJ: Are policy makers educated enough about how technology

works? If not, what do they not understand?

MS. O'CONNOR: Government entities of all kinds lag behind the

private sector. That's because we've got this vibrant tech sector

in places like Silicon Valley and Austin, Texas, with really

exciting and innovative job opportunities, but not a core stream of

tech-focused jobs in agencies on Capitol Hill. I'm curious if we

shouldn't have more technologists serving in our judiciary. Courts

are making decisions on really consequential issues of technology

and data, yet you have sitting on the bench [people who are] just

recently adopting smartphones and things.

PROF. NOVECK: There's obviously catch-up that all of us have to

play with regard to the adoption of new technology. Government in

particular has very definite challenges in this regard. The

government has existing legacy systems with not-infinite time or

budget to be able to transition them to the latest cloud-based

software or service. You also don't have a large number of people

in the front office of the policy shop tied to thinking about how

technology is serving political priorities.

WSJ: What can be learned from Facebook Inc.'s mishandling of

user data via data firm Cambridge Analytica?

MS. O'CONNOR: We need greater control and scrutiny over

secondary uses of data that you give to one company for a

particular purpose. We also need greater control over any

third-party data sharing. Secondary uses and third-party transfers

to me are the very big bucket of things that people are deeply

concerned about, especially when it comes to biometric and

immutable or intimate data. Immutable are things that are attached

to my body or my voice. And intimate are things that many people

would consider embarrassing if revealed outside of their family or

their private relationships with certain companies.

PROF. NOVECK: We have a desperate need for a political class

that understands these technologies or creates processes for

engaging with more people who understand these technologies. You

can't expect a politician to know everything on every topic. It

isn't just tech; it's farming or space or health care. We expect

our politicians to be jacks of all trade, and we know that they are

masters of none.

Ms. Ma is an editor for The Wall Street Journal in New York.

Email her at michelle.ma@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 11, 2018 08:58 ET (13:58 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

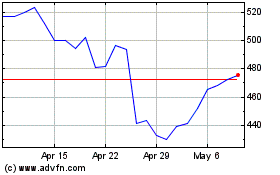

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024