Big Banks Tweak Business Plans to Avert New Regulator Costs -- 3rd Update

October 04 2016 - 7:55PM

Dow Jones News

By Donna Borak and Emily Glazer

Five of the country's biggest banks detailed tweaks to their

business models in hopes of persuading regulators they could absorb

significant financial distress without requiring taxpayer funds to

stay afloat.

The stakes are high for J.P. Morgan Chase & Co., Bank of

America Corp., and three others. If regulators deem these revisions

of their so-called living wills -- made public by the government

Tuesday -- to be insufficiently credible, those institutions could

be ordered to hold higher levels of capital on their books, or to

restructure and shed business lines.

Regulators are facing considerable pressure from politicians to

use this process to break up the biggest banks, with many --

notably Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren -- arguing

these institutions remain "too big to fail."

Federal regulators had declared in April that earlier plans

submitted by those two banks -- along with Wells Fargo & Co.,

Bank of New York Mellon Corp., and State Street Corp.--didn't show

sufficiently how they could wind down their operations in an

orderly fashion, and told them to address weaknesses by Oct. 1.

In the latest public versions of the plans -- each running

around 50 pages -- the firms laid out modest changes to their

business operations to address what regulators had branded

"deficiencies" in their original documents, such as giving more

detailed explanations for how they would unload assets, or putting

top managers in charge of bankruptcy planning. The firms also

submitted considerably longer living wills that won't be made

public.

The agencies in charge of the process -- the Federal Reserve and

the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.--said in a press release they

hadn't yet reviewed the plans and "will now be initiating their

process for review." The agencies didn't say how long the process

would take.

The living wills requirement was created by the 2010 Dodd-Frank

financial overhaul law, enacted in the wake of the financial crisis

to, among other things, prevent a recurrence of government bank

bailouts.

This is the third round for the major banks. In 2012, they

submitted plans but didn't get any individual feedback. In 2014,

the Fed and FDIC rejected all the plans. This year, they kicked

back five, seeking revisions, and cleared three -- from Goldman

Sachs Group. Inc., Morgan Stanley and Citigroup Inc.--though the

regulators still said those plans had "weaknesses" and

"shortcomings." Those three firms submitted updated plans that were

also made public Tuesday.

J.P. Morgan said it had altered its business organization to

create a new "intermediate holding company" and has moved assets

into the unit, which would be ready to inject immediately capital

and liquidity into distressed subsidiaries. Bank of America said it

had moved assets into a pre-existing intermediate company for this

purpose.

These moves are aimed at meeting regulator questions about the

banks' abilities to estimate liquidity resources and needs in times

of stress, and the lack of a formal agreement to assure support for

those subsidiaries.

J.P. Morgan also said it had identified 16 "objects of sale"

along with potential buyers who could pick up the properties

quickly.

Wells Fargo said it, too, had crafted a more detailed playbook

for potential "strategic sale transactions." And the bank said it

is giving more responsibility for living will planning to top

executives. Wells Fargo President Timothy J. Sloan now oversees all

recovery and resolution planning initiatives. Chief Financial

Officer John Shrewsberry now leads the formal management governance

committee related to living wills, and that committee now includes

senior executives from "key support groups" including the bank's

controller, head of corporate enterprise risk and the chief

technology officer.

If regulators don't consider those moves sufficient, they now

have the power to raise capital requirements or even force

divestitures, as they see fit. Both agencies -- the Fed and FDIC --

would have to agree on whether the proposed fixes by the firms are

adequate, and if not, what the appropriate action would be to

take.

There is no set time frame on when they must reach a

decision.

"It's all about starting the clock to give the agencies the

authority to use some powerful tools if banks are unable to

remediate those deficiencies," said John Simonson, a principle at

consulting firm PwC and a former FDIC official.

John Carney contributed to this article.

Write to Donna Borak at donna.borak@wsj.com and Emily Glazer at

emily.glazer@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 04, 2016 19:40 ET (23:40 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

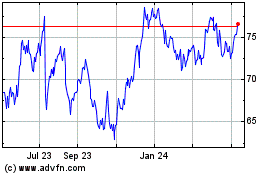

State Street (NYSE:STT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

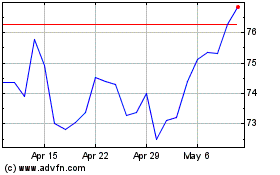

State Street (NYSE:STT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024