In the spring of 2010, I appeared on CNBC and Bloomberg TV and

spoke about the revelations for markets concerning French bank

exposure to the Greek debt crisis. I was one of the first to say

that Europe's sovereign debt worries were then growing from a mere

government problem to a systemic banking crisis very similar to the

US one.

At the time, it was considered a fairly big deal

that France's top three commercial banks owned such a large

majority of Greece's public debt totaling over $80 billion. This

month, as the fortunes of Italy and Spain tremble, we have learned

French banks own debt of theirs totaling hundreds of

billions.

This is why, of course, European officials stepped

into markets Thursday with a ban on short-selling of banks and

other financial institutions. Will it stem the tide of losses and

erosion of capital ratios?

Probably not any better than it worked here in

2008. But the more interesting questions I’ve been pondering are,

"If it was so bad, why weren't these banks in free-fall months ago

and why is the euro currency still holding up so well above

$1.40?"

Will the Euro Survive?

I wrote a piece reviewing some of these questions

in June (linked above). Based on how well Europe's banking system

had weathered the mud of its PIIGS for 18 months up to that point,

I thought their crisis would have little effect on our economy.

And maybe that's what lots of other big investors

and strategists thought too. Here's what I wrote in June...

"And you have to consider that from crisis,

often comes a new equilibrium. When you accept that Europe has its

own unique problems, just like the US and its burgeoning municipal

debt crisis, it's hard to say how things will resolve.

Who predicted the near collapse of the US

financial system? And who predicted its amazing recovery from the

abyss? Not many.

As Moody's Investor Service warned last week,

three of France's top banks could be in for a credit downgrade as

they continue to use cheap US dollar funding to roll their large

exposure to Greek debt.

BNP Paribas, Crédit Agricole and Société

Générale may all be playing hot potato with debt of a deteriorating

quality, borrowing over $75 billion on the short end to finance

their longer-term holdings of Greece government paper."

Tip of the Iceberg

This was the mood of quiet toleration (heads in the

sand?) before we learned how much Italian debt they owned. So the

selling of these top three banks really didn't even begin until

July, weeks after the Moody's warnings and awareness of "the

Italian problem" heated up.

Here's a summary of their declines before the

short-sale ban (priced in euros) since July 1, when two of the

three were close to their 52-week highs and the third, Soc Gen, was

still within 20%.

BNP Paribas (BNP:FP) -- 55 down to 33 euros

(40% decline to lows)

Societe Generale (GLE:FP) -- 42.50 down to

20 euros (53% decline to lows)

Credit Agricole (ACA:FP) -- 11 down to 6

euros (45% decline to lows)

Chanos Chimes In

Notorious short-seller Jim Chanos gave an

interesting quote to Bloomberg.com for its story, "Short Selling of

Stocks Banned in France, Spain" by Howard Mustoe and Jesse

Westbrook:

"EU policy makers don’t seem to understand the law

of unintended consequences. The vast majority of short-selling

financial shares is by other financial institutions, hedging their

counterparty risks, not speculators. The interbank lending market

froze up completely in October to December 2008 -- after the

short-selling bans."

This is exactly what we learned back then. I was

working for a large options market maker in Chicago and the

"unintended consequences" were numerous and obvious to us,

especially as market makers were at first not exempt from the ban,

eliminating their ability to hedge and provide liquidity to markets

in both options and stocks.

The Europeans got the market maker part right this

time, but volatility may still rise because hedge funds who

normally try to strike some balance between long and short

positions will be leaving the market, the Bloomberg story goes on

to explain.

A Moby Dick of Fears, Besides GDP

So, while I have been writing for two weeks about

this sell-off being mostly a function of lowered growth

expectations since the awful GDP revisions of July 29, I should

consider that the banking crisis finally unfolding in Europe has

been a big catalyst too.

Like a sea monster you can"t see under the surface,

the vaguely familiar unknowns trouble institutional investors who

remember 2008, even if our economy and banking system are much more

sound.

We grew accustomed to Europe's debt crisis, as if

it were unfolding in slow motion. Just another part of the daily

headlines, it didn't bother us as much. And as with all crises of

confidence, especially those involving banking, they don't really

matter until they do and things implode. In other words, until the

creature bumps into your boat and makes its presence very real and

known.

The Big Question Now for the US Economy

If Europe's crisis does devolve into a wholesale

systemic crisis that freezes their markets and economies, what

impact will that have on a US economy at stall speed?

Everyone talks about the impact of fear on the

American consumer, as if we can collectively talk ourselves into a

recession with negative headlines that weaken and dispel confidence

-- and spending. But I think the American consumer has proven

amazingly resilient since our crisis. His and her expectations

about jobs and credit and growth are much more reasonable and

realistic, if subdued. That's good right now.

I am more worried about the impact of fear on these

two groups of spenders: institutional investors, primarily equity

portfolio managers, and CEOs and their purchasing managers. If

these people are uncertain about the future and lack confidence in

growth prospects, this will become a self-fulfilling feedback loop

that can cause recession.

Earlier this week, I wrote "QE3 and the Probability

of Recession" in which I shared a chart of the Federal Reserve's

last growth forecast from June. And while I look forward to their

update since they got it wrong -- and got the bad news to prove it

on July 29 -- I am even more eager to see and hear the projections

and concerns of money managers and heads of industry.

Since the S&P derives 45% of its earnings from

abroad, and Europe's contribution is easily one-third of that, a

fallen EU is a big blow to the US economy. Viewing the current 15%

correction in equities (I'm using the drop in the S&P 500 from

roughly 1,350 to 1,150 to get 15%) as an extremely quick

discounting of the increased "probability of recession," I still

expect the market to trade sideways for the next few weeks until we

get more information.

Pricing in Blah

Here are some numbers to keep in mind until we

start to get lower growth forecasts and downward earnings estimate

revisions after Labor Day:

Estimates as of August 1 were for the S&P 500

to earn about $98 per share in 2011. Let's say that realistically

the best we could expect now is $95 EPS. At an index level of

1,200, that's a "working" P/E of 12.6.

If you bump EPS down to $85, at 1,200 the S&P

still looks cheap at 14 times. The catch is that if earnings and

GDP are still declining, then money managers and CEOs will continue

to price in lower expectations. Right now we wait for more

data.

In "How Long Will the Correction Last?" from August

5, I wrote the following about where we stand...

"I think the highest-probability scenario is a

'wait and see' by institutional investors. That means to me that

the S&P will range trade between 1150 and 1250 for the next 2-3

months, in waves of pessimism and optimism, until more visibility

on GDP, jobs, cap ex, manufacturing, and corporate earnings rolls

in.

What are the chances that this advance 'pricing-in

of the recession' heats up and we dip below S&P 1,100? I'll say

about 40%, right around where I think the probability is for an

actual recession.

Use my probabilities as a rough guide and trade

your own view accordingly. Many strategists from major investment

houses, managing trillions of dollars in aggregate, have similar

projections.

The hard part is that on big sell-off days, they

look like they are more scared than they really are."

Investing Without Certainty

During this tumultuous two weeks, I've done many

interviews with financial media, both TV and print. When asked by

AARP what I thought senior investors should be doing with their

money, I became very cautious, thinking of my own parents and their

retirement concerns.

But then I just stepped back and framed the

question as any investor should by moving away from emotion and

just thinking rationally about time horizon. Here's what I said on

Monday...

"If one has ten years left in the market, it's a

no-brainer to be putting money to work in stocks. There are lots of

buying opportunities to take advantage of right now in stocks like

Apple (AAPL), Eaton (ETN), and National Oilwell

Varco (NOV).

If you have five years left for your money to work

for you, there are still stocks and sectors like energy,

technology, and materials that one should be accumulating at these

levels. But for those who need their money in the next two years,

it's a good time to just sit back and see how this unfolds into

October earnings season.

Given a 40% chance we slip into recession,

institutional investors -- who move the market in aggregate with

the trillions of dollars they manage -- will be waiting for more

bloodwork on the economy and earnings before they return to the

business of investing."

Kevin Cook is a Senior Stock Strategist for

Zacks.com

APPLE INC (AAPL): Free Stock Analysis Report

EATON CORP (ETN): Free Stock Analysis Report

NATL OILWELL VR (NOV): Free Stock Analysis Report

Zacks Investment Research

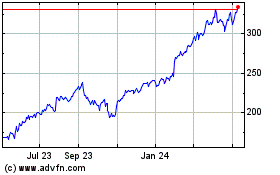

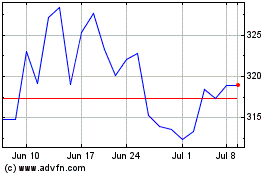

Eaton (NYSE:ETN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

Eaton (NYSE:ETN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024