By Hannah Karp

How many companies can survive in the high-cost music-streaming

business? Plenty, it appears -- as long as music isn't their main

source of revenue.

Streaming music is just a sideline for the industry's power

players -- Apple Inc., Amazon.com Inc. and Alphabet Inc.

Even so, their influence looks likely to grow. Apple is

revamping its Apple Music app while exploring an acquisition of

streaming service Tidal. Amazon, meanwhile, is preparing to

introduce a stand-alone $10-a-month subscription music service,

matching the subscription fee charged by Apple Music and by

Alphabet, which offers ad-free music through both its YouTube Red

and Google Play Music service.

For the tech companies, paid streaming services aren't just a

new revenue stream. Their strategy is to use the services as bait

to attract customers and hang on to them longer, so they can sell

them something else.

Apple is using its year-old Apple Music service to spur its

sales of iPhones and other Apple devices.

E-commerce giant Amazon, which aims to launch its subscription

service in coming months, mainly wants to encourage customers to

shop. To access Amazon's existing Prime Music service, a customer

needs to be a member of its $99-a-year Prime program.

Alphabet's Google Play Music service and the nine-month-old,

ad-free YouTube Red service from the company's online-video unit

add just a relatively tiny trickle to the company's revenue

streams. But YouTube Red has driven significant traffic to

YouTube's ad-supported site, its core business, according to a

person familiar with the matter.

Because streaming music advances their other ambitions, Apple

Music, Amazon, Alphabet's Google and YouTube units, don't need

their services to be hugely profitable, though none of them are

selling subscriptions at prices that suggest a willingness to lose

money. That gives the tech companies a major advantage over smaller

companies like Pandora Media Inc., Spotify AB and French

counterpart Deezer, whose main businesses are music streaming.

"I think that any company that has some other motive [for

offering streaming] is going to win," said Paul Young, a

music-business professor at the USC Thornton School of Music.

That is at least partly because the music-only companies are

burdened by heavy costs. The paid services typically spend 70% of

their revenue on licensing music and much of the rest on acquiring

customers.

That makes their margins "far too tight," according to Les

Borsai, a music-technology consultant. "The only solution is to

create more value with additional offerings -- aka more than just

music -- and perhaps an increase in pricing, or both."

The services are also at the mercy of the tech companies that

distribute their apps. Apple collects a 30% fee on in-app

purchases, including music subscriptions, so it has an interest in

supporting popular music apps other than its own. But it recently

rejected an update to Spotify's app that didn't comply with Apple's

guidelines.

In a letter to Apple, Spotify's top lawyer called the move

anticompetitive. But Apple's general counsel dismissed that claim,

adding that one of the features at issue with the app was intended

to avoid "having to pay Apple," according to the company's general

counsel.

For the recording industry, the tech titans' embrace of music

streaming has been positive so far, a contrast with Apple's

dominance of digital-music sales.

Record companies are happy to have Apple, Amazon and Alphabet,

three of the country's biggest companies, competing to sell music

subscriptions, as sales of compact discs and digital music continue

their yearslong decline. And there is some evidence they have made

consumers more willing to pay for services. In Canada, consumers

surveyed by Nielsen Music last year said they would pay an average

of $9 a month for unlimited music, up from about $6 in 2014, before

the advent of Apple Music.

But independent streaming services are still crucial because

they tend to drive innovation, and "ensure as an artist, and as an

industry, that you continue to have a direct route to the audience

[and] an option to control your own destiny," said Erik Huggers,

chief executive of Vevo LLC, the music-video platform owned by

Vivendi SA's Universal Music Group and Sony Corp.'s Sony Music

Entertainment.

Spotify, whose owners include the major record labels, has

amassed about 30 million paying subscribers for its $10-a-month

service and 70 million free users in eight years, but its operating

losses widened to more than $200 million last year, despite an 80%

jump in revenue to about $2 billion. The company, valued at $8.5

billion a year ago, raised $1 billion in convertible debt earlier

this year, giving it more room to lose money without raising more

equity.

Spotify declined to comment.

Tidal, which rap star Jay Z launched last year after buying its

corporate parent for $56 million, has built up 4.2 million

subscribers, most of them this year, with a string of exclusive

releases from some of its 20 artist shareholders. But Tidal's

subscriber numbers suggest it is a long way from profitability.

Tidal declined to comment.

Deezer called off an initial public offering in October, citing

"market conditions," and subscription service Rdio filed for

bankruptcy late last year and sold its assets to internet-radio

company Pandora, which is aiming to launch new subscription

offerings later this year.

Write to Hannah Karp at hannah.karp@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 24, 2016 18:54 ET (22:54 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

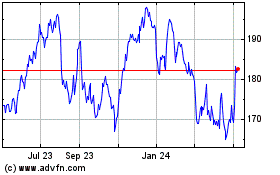

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

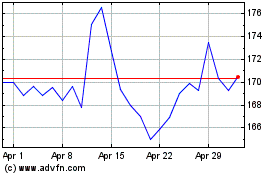

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024