By Asjylyn Loder

For State Street Corp., the company that pioneered the $5

trillion exchange-traded fund industry, it's been a long way

down.

Last week, the Boston firm reported that investors took out as

much cash as they put into its $639 billion ETF business this

spring. It was the worst showing among the three largest issuers

and sent State Street's share of the U.S. ETF industry to an

all-time low.

State Street launched the first ETF 25 years ago and dominated

the market for a decade. Today, its slice of U.S. ETF assets is

just 17.3% -- down from 49% 15 years ago. More worrying for its

future, State Street captured just 5.9% of the $343 billion that

poured into ETFs in the past year. By contrast, Vanguard Group and

BlackRock Inc.'s iShares took in a combined 67%. Even Charles

Schwab Corp., a relative newcomer with just 22 ETFs, had a fatter

haul.

How State Street squandered its first-mover advantage for one of

the most popular financial products ever created shows that being

first can sometimes be as much of a hindrance as a head-start.

It's easy to point out State Street's missteps in hindsight, but

no one knew then how big the ETF industry was going to be, said Jim

Ross, chairman of State Street's global SPDR business. "If you go

back 25 years, you can think of some things you might do

differently," he said.

To be sure, State Street is still the third-largest ETF issuer,

but it has been hamstrung by a product suite that's vulnerable to

market whims. It has struggled to connect with mom-and-pop

investors. Some of its most popular funds are burdened by

decades-old agreements that make State Street's funds more

expensive than the competition's, a disadvantage in an industry

where the cheapest funds win the most assets.

State Street doesn't even own the brand name of its ETF

franchise, and instead pays hefty fees to rent it from index

provider S&P Global Inc.

Nowhere are State Street's problems more apparent than in its

flagship fund. The SPDR S&P 500 ETF Trust, best known by its

ticker SPY, has swelled into a $269 billion behemoth and is one of

the most-traded securities on the planet. But it has seen $4.2

billion in investor withdrawals in the past year while nearly

identical products from BlackRock and Vanguard -- which cost half

as much -- gained a combined $26.3 billion.

Named after Standard & Poor's Depositary Receipts, shortened

to SPDR (pronounced "spider"), SPY was the first to package every

company in the S&P 500 index into a single share that, unlike a

mutual fund, could be bought and sold on the stock exchange. The

now-defunct American Stock Exchange celebrated SPY's January 1993

debut by hanging a 9-foot inflatable spider over the trading floor

and giving out hundreds of plastic spider rings.

SPY was a far bigger hit than its inventors had predicted, and

State Street followed with new ETFs pegged to other stock indexes,

including the popular sector ETFs that invested in industries like

energy and technology.

But there were early signs of trouble. The staid Boston

institution has long treated its ETF business as an afterthought

compared with its far larger businesses in trust banking and asset

management for major institutional investors.

Earlier in July, State Street's share price plummeted after the

firm announced it was buying a financial-data firm and canceling

planned share buybacks. In the earnings call that followed, ETFs

were barely mentioned.

"The ETFs were a small part of a big bank that didn't get this

business, " said John Jacobs, a former Nasdaq executive who

launched the popular Nasdaq 100 ETF in 1999. "They were really,

really conflicted about how much to put into the business and how

much to go after it."

When a quirky San Francisco offshoot of Barclays PLC rolled out

dozens of new iShares ETFs in mid-2000, State Street was slow to

perceive the threat. In the years that followed, the upstart hired

a massive sales force, sponsored a Tour de France team (later

dropped amid doping allegations) and backed a catamaran racing

series that traveled the world, iShares emblazoned on the

sails.

IShares unseated State Street as the world's largest ETF issuer

in early 2004 and widened its lead in the years that followed.

Vanguard, too, pushed into the market, and its low-cost funds

quickly began gobbling up market share.

State Street was caught flat-footed. Its ETFs were sold under

multiple brand names. The ideas for its biggest successes, notably

SPY and the sector ETFs, had come from outside the firm. In fact,

State Street nearly declined the World Gold Council's idea for a

bullion-backed ETF. The fund, better known by its ticker GLD, is

now one of State Street's most lucrative.

To amp up its brand recognition, State Street consolidated all

of its ETFs under the SPDR name in 2007, but there was a downside:

The SPDR trademark belongs to S&P. When it expanded its use of

the name, State Street also extended until 2031 a contract under

which S&P gets one-third of the fees paid by SPY's investors.

S&P's cut alone -- $3 a year for every $10,000 invested -- is

almost as much as the entire fee BlackRock and Vanguard charge for

their comparable funds.

Between SPY and other fee-sharing arrangements, State Street

paid almost $143 million to S&P last year, more than triple the

licensing, data and other fees paid by Vanguard and almost double

those of BlackRock, which bought iShares from Barclays in 2009.

Those legacy contracts make it difficult for State Street to

match aggressive price cuts from BlackRock and Vanguard, especially

after BlackRock launched an ultra-low-cost ETF lineup in 2012.

Compounding the problems, the fallout from the financial crisis

left State Street financially hobbled. In 2011, activist investors

urged the firm to sell off the investment-management division.

Market share kept falling, along with morale in its ETF

business.

The firm hired a consultant to figure out where it had gone

wrong. Some of the client feedback was scathing. Customers called

State Street "amateurish" and "plain vanilla" compared to the

"rocket scientists" at the competition, according to a copy of the

2013 report reviewed by The Wall Street Journal.

Executives summoned dozens of managers to a two-day meeting at

Babson College in October 2013, a few miles from its Boston

headquarters. The message: State Street needed a comeback. But some

of State Street's ETF veterans grumbled that the firm had paid

consultants to repeat what they'd been telling their bosses for

years.

Following the report, State Street recruited several new

executives, among them iShares alum Rory Tobin, who is now head of

the SPDR ETF business.

Shortly after he arrived, Vanguard overtook State Street as the

second-largest ETF issuer, and State Street's market share

continued to fall as investors flocked to the cheaper ETFs offered

by BlackRock and Vanguard.

"When I started here in December 2014, I was struck by the way

it was organized -- or maybe the degree to which it was not

organized -- the way iShares was," Mr. Tobin said.

State Street has since restructured its fragmented ETF business,

an ongoing process that included an overhaul of its sales force

last year, Mr. Tobin said.

One of the biggest changes was State Street's introduction of

its own low-cost lineup last October, a move that industry analysts

viewed as long overdue. The funds have since attracted more than

$16 billion in new investor cash. But just as it took years for

State Street to squander its lead, it will also take years to

regain its former dominance, if it can.

"It's step by step," Mr. Tobin said. "I'm not going to say

there's a silver-bullet answer that gets us back up to significant

market share."

Write to Asjylyn Loder at asjylyn.loder@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 27, 2018 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

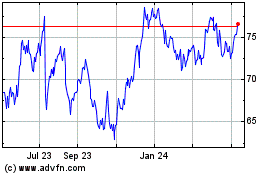

State Street (NYSE:STT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

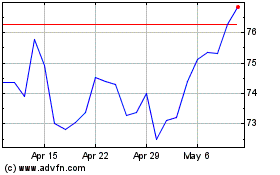

State Street (NYSE:STT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024