By Brent Kendall

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (November 27, 2018).

WASHINGTON -- Apple Inc.'s exclusive market for selling iPhone

apps came under fire at the Supreme Court Monday, as justices

considered whether consumers should be allowed to proceed with a

lawsuit alleging the company has an illegal monopoly that produces

higher prices.

The plaintiffs are a group of consumers challenging Apple's

requirement that all software for its phones be sold and purchased

through its App Store. Their class action lawsuit seeks damages on

behalf of people who have purchased iPhone apps.

App developers can only reach iPhone users through Apple's

store, and the company charges the developers a 30% commission.

"Apple directed anti-competitive restraints at iPhone owners to

prevent them from buying apps anywhere other than Apple's monopoly

App Store," plaintiffs' lawyer David Frederick told the court

during an hour-long oral argument. "As a result, iPhone owners paid

Apple more for apps than they would have paid in a competitive

retail market."

The case comes to the court on the preliminary but critical

question of who has the legal right to sue over Apple's alleged

monopoly. If the justices allow the lawsuit to proceed, the case

has the potential to force changes to how apps are sold, and it

could expose Apple to a significant monetary judgment if the

company is found to have violated antitrust laws.

The iPhone maker argues that consumers can't sue because the

company doesn't directly set app prices, a responsibility that lies

with the app developers. Apple says it only serves as a conduit,

and consumers aren't really buying apps from the company.

If anyone can sue over the alleged monopoly, Apple says, it

would be the app developers themselves, since they're the ones

paying to feature their software in its App Store. The developers

"are buying a package of services, which include distribution and

software and intellectual property and testing," lawyer Daniel M.

Wall, representing Apple, told the court.

Apple in a statement said it provides "a safe, secure and

trusted storefront for customers" that has fueled app growth,

"leading to millions of jobs in the new app economy and

facilitating more than $100 billion in payments to developers

worldwide."

None of the justices grew up with smartphones or the internet,

as they sometimes point out themselves in court, but in this case

it was clear they had familiarity -- and personal experience --

with the issue.

"I pick up my iPhone. I go to Apple's App Store. I pay Apple

directly with the credit card information that I've supplied to

Apple. From my perspective, I've just engaged in a one-step

transaction with Apple," said Justice Elena Kagan. She suggested

that kind of direct commercial relationship with the company was

enough to give consumers a right to sue.

The court's other three liberal justices voiced similar

views.

Some conservative justices also questioned Apple's position,

although at times for different reasons. Justices Samuel Alito and

Neil Gorsuch questioned the propriety of a Supreme Court precedent

from 1977 -- relied upon heavily by Apple -- that under federal law

limits claims for antitrust damages to immediate victims of the

anticompetitive conduct.

That case prohibits a purchaser from suing someone a few links

earlier in the supply chain simply because higher prices were

eventually passed on to them. Justices Alito and Gorsuch, however,

suggested that 40 years of economic evidence has undermined the

logic of the court's earlier ruling.

"I really wonder whether, in light of what has happened since

then, the court's evaluation stands up," Justice Alito said. He

asked whether any of the tens of thousand of app developers had

ever sued Apple.

No, said Mr. Wall. He noted that "no state or federal antitrust

agency has ever sued either," suggesting the lack of legal action

could reflect the absence of any anticompetitive behavior on

Apple's part.

The Supreme Court hasn't explicitly said it would consider

overruling past precedent in the case -- which it generally does

when that is a possibility -- so it's not clear how Monday's

discussion will factor into the outcome. A federal appeals court

previously allowed the lawsuit against Apple to proceed, and the

Supreme Court is considering that ruling.

Chief Justice John Roberts spoke most sympathetically of Apple's

position, echoing the concern behind the 1977 ruling that companies

could face dueling lawsuits and duplicative financial damages from

different groups of plaintiffs over the same behavior.

Apple's app distribution system for iPhones is different from

what consumers use for phones issued by an array of companies that

operate on the Android system developed by Alphabet Inc.'s

Google.

In addition to Google Play, the leading Android app store in the

U.S., there are a number of smaller stores, including those

provided by Amazon.com Inc. and Samsung Electronics Co. Developers

such as Epic Games Inc., the maker of Fortnite, also have gone

direct to consumers using Android.

Apple's iOS operating system has a 40% market share in the U.S.

compared with Android's 60% share, according to Kantar Worldpanel,

a market research firm.

The Supreme Court's decision is expected by the end of June.

--Tripp Mickle contributed to this article.

Write to Brent Kendall at brent.kendall@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 27, 2018 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

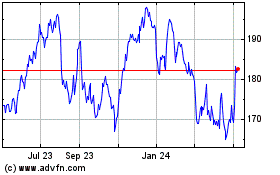

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

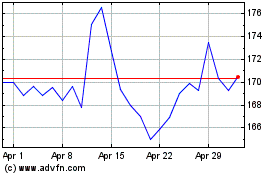

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024