By Theo Francis

A little more than a year on, companies are only just gearing up

to put the 2017 tax overhaul to work.

For investors, that means it is time to keep a close watch on

whether -- and how -- companies begin to adjust their operations to

the new tax reality.

Much of the biggest change in the first year was on paper. First

came the dramatic charges to earnings from accounting adjustments

and big one-time tax bills. Then, as the Treasury Department and

the Internal Revenue Service began issuing sheaves of guidance and

new regulations to implement the tax law, companies calculated --

and sometimes recalculated -- the impact on their financial

statements.

Many of the new tax rules remain in preliminary form. But the

outlines are firm enough that companies are beginning to understand

how they could reshape operations and refashion existing plans.

What remains unclear is just how they will take advantage of

this new landscape. The changes are complex enough -- most of the

rules governing international tax are wholly new, for example --

and interlocking enough that there are few rules of thumb: What

works for one company may not for another.

Still, understanding some basics about the tax legislation can

help investors evaluate new disclosures in the months and years

ahead. Here is a closer look at some of those basics:

Foreign profits

The tax law's shift to a type of territorial tax system has the

potential to pay off for multinational companies for years to

come.

Under the former tax system, when companies committed to

reinvesting foreign profits outside the U.S., they could avoid

paying U.S. tax on the profits indefinitely. Now, new payments from

foreign affiliates to U.S. parent companies should generally go

untaxed by the U.S., with exceptions meant to discourage

multinationals from artificially shifting profits to tax

havens.

All told, companies over the next decade can expect to save

$223.6 billion in the form of reduced taxes on foreign profits,

according to congressional estimates. And that probably

underestimates the value of other benefits to companies. With taxes

on foreign income greatly reduced, executives say they will have

readier access to their cash and more flexibility in how they spend

it.

Through late September, U.S. companies shifted $571.3 billion to

their U.S. operations from foreign subsidiaries, far more than in

past years but still only a portion of the estimated more than $2

trillion they had accumulated overseas over the years. And the

transfers slowed sharply during the year: By the third quarter,

repatriations from foreign units fell below foreign profits --

meaning they were once again accumulating profits outside the

U.S.

What remains less clear is where and how companies are going to

spend it. So far, much appears to have gone to share buybacks.

S&P 500 companies set three consecutive quarterly records for

share repurchases, reaching $203.8 billion in the third quarter,

according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. Dividends, too, set a

record in 2018, at $456.3 billion.

How much companies plowed into capital expenditures is less

clear. Most companies have been slow to tie new U.S. investment to

the tax overhaul. Biotech firm Amgen Inc. said in early 2018 that

it would spend three quarters of its five-year, $3.5 billion

capital program in the U.S., up from 50% previously. Apple Inc.

announced, to much fanfare, a $1 billion, 5,000-person Texas

project as part of its earlier commitment to invest $30 billion and

create 20,000 U.S. jobs over five years. Overall, federal data

suggest, capital spending surged early in 2018 before slipping back

to more typical growth trends.

Better access to foreign profits appears to also be affecting

corporate borrowing demand, Bank of America Corp. Chief Financial

Officer Paul Donofrio told investors early this year. "Tax reform

has increased cash flow, and repatriation has also increased cash

available for debt paydowns," he said in a mid-January conference

call. He said the company's expectations for loan growth in the

near term haven't changed.

Multinational companies previously borrowed heavily to pay

dividends, buy back shares and invest in the U.S., because it was

cheaper than using foreign profits and incurring U.S. taxes in the

process.

Now, there are signs those companies are reducing their debt

loads, freeing up yet more future income and cash for operations or

returning capital to shareholders. Boilermaker A.O. Smith Corp.

said in late October that it had repatriated almost $300 million,

which went to repurchasing shares and paying down floating-rate

debt.

The biggest winners remain those companies that had accumulated

huge troves of cash parked overseas -- primarily tech and

pharmaceutical firms, but also some large industrial, financial and

consumer-products companies.

Lower rates for most

Most of the tax benefits for U.S. companies have remained right

here at home.

Reducing the corporate tax rate to 21%, Congress estimated when

the law was passed, would save companies $1.35 trillion in taxes

through 2027 before considering tax breaks eliminated by the

legislation. Companies stand to save an additional $40 billion over

the decade thanks to the elimination of the corporate alternative

minimum tax. The corporate AMT previously limited the degree to

which many companies could reduce their domestic taxes with

deductions and credits.

Those benefiting the most are domestic-focused companies and

others that used to pay close to the old 35% statutory tax rate.

Organic- and natural-foods distributor United Natural Foods Inc.,

which has been a big supplier to Amazon.com Inc.'s Whole Foods

supermarket chain, said its effective tax rate for continuing

operations declined to 16.6% in the quarter ended Oct. 27 from

41.8% a year earlier. Darden Restaurants Inc. reported an effective

tax rate of 8.5% in the six months ended Nov. 25, down from 23.1% a

year earlier, and said it expects a full-year tax rate of 10% to

11%. Mutual-fund firm T. Rowe Price Group Inc. recently said it

expects its 2019 effective tax rate to be between 23.5% and 26.5%,

down from closer to 34% before the tax overhaul.

Companies with hefty foreign operations -- and especially those

depending more on income from intellectual property, or that

shifted patents and profits to low-tax foreign havens -- have seen

their tax bills shrink less, or even rise. Many tech and

pharmaceutical giants fall into this category.

Accelerated depreciation

The new tax law gives companies a big break when they buy stuff.

This break -- full and immediate depreciation for purchases --

applies to a variety of tangible assets, including factory

equipment, machinery and vehicles acquired after late September

2017 and phasing out after 2022 for most purchases. Previously,

such deductions were spread over longer time periods.

There is a twist: The accelerated depreciation applies not only

to new assets, but to used assets as well. Still, don't expect a

dramatic, direct impact on profits for publicly traded companies.

From a financial-accounting perspective, companies have long had to

book full deductions on equipment purchases upfront.

But from a cash perspective, it is a big change that can mean

significantly less taxes paid in the wake of big purchases. It

helped boost equipment sales early in 2018.

The tax break can also help corporate acquisitions, too, to the

extent the acquisition involves tangible assets. For deals

structured as asset purchases, buyers can get as much as a 21%

discount on the cash purchase price thanks to the new depreciation

rules. Acquiring a partnership is automatically treated as an asset

purchase, while the same treatment can apply to acquiring other

pass-through entities, such as S corporations or divisions of C

corporations.

That has big implications for companies that acquire smaller

local or regional competitors.

Stock acquisitions, such as when one public company acquires

another, don't qualify. But acquiring a division of a public

company can be structured as an asset purchase that qualifies for

the immediate deduction. And note that regulated utilities don't

get the new capital-expensing treatment; they gave it up to keep

existing interest-deduction rules, which changed for most

companies.

Vanishing breaks

Some existing tax breaks vanished or shrank sharply, including

one for domestic manufacturers (saving the federal government $98

billion over 10 years) and one for pharmaceutical companies

developing "orphan" drugs for rare conditions ($32.5 billion).

Like-kind exchanges -- where two companies trade similar assets and

postpone any tax impact -- are now limited to real-estate swaps

(saving Uncle Sam $31 billion in forgone revenue). And some

fringe-benefit deductions were scaled back ($41.2 billion).

Mostly, however, companies view these minuses as a small price

for significantly lower tax rates and the new territorial tax

system.

Interest deductions

For some companies, the change to interest-expense deductions

can be substantial. Previously, companies could generally deduct

the interest they paid each year. Now they may deduct no more each

year than 30% of a figure similar to Ebitda, or earnings before

interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization, plus the value of

interest income. Surplus interest expense can be carried forward

indefinitely, however, and no longer expires. Auto and other

vehicle dealers have special rules, and real estate and regulated

utilities generally aren't affected.

Many companies haven't been seriously affected by this change,

but highly leveraged companies can feel a pinch. One analysis found

that the health-care sector had the biggest proportion of public

companies in 2016 with interest payments in excess of the

threshold, at more than 75%, followed by energy, at about 70%, and

business-equipment firms, at 45%. By contrast, about a third of

chemical companies paid more interest than they could deduct under

the new rules.

Starting in 2022, the interest-deduction limit is slated to get

more strict and affect more companies.

The legislation also reined in the degree to which companies may

use net operating losses to reduce future taxes -- and eliminated

the ability to get retroactive refunds. That could make it tougher

for companies to recover from unexpected downturns or other

setbacks, bankruptcy experts say.

Guardrails

The U.S. will continue to tax some foreign earnings of U.S.

companies.

Complex provisions attempt to prevent U.S. businesses from

abusing the new tax law by artificially shifting income to

ultra-low-tax havens overseas. Rules to implement these guardrails

have been proposed, but still must be finalized. One, the base

erosion and anti-abuse tax, or BEAT, applies to large companies

with at least $500 million in gross receipts and significant

cross-border transactions with related entities. For the provision

to raise a company's taxes, at least 3% of a company's tax

deductions must stem from cross-border payments to foreign

affiliates. (The threshold is 2% for banks.)

Companies to which the BEAT applies must effectively calculate

an alternative tax amount without deductions for cross-border

payments -- then pay that new tax if it is higher than a modified

version of their ordinary figure. Certain kinds of deductions

aren't stripped out, including for cost of goods sold -- so a

manufacturer doesn't trigger the additional tax solely because it

imports parts from a foreign affiliate.

Although meant primarily to prevent companies from "stripping"

U.S. profits by transferring them to foreign units without paying

U.S. tax, the measure is snaring plenty of big service companies,

including Western Union Co., Accenture PLC and Willis Towers Watson

PLC.

The other primary guardrail, dubbed the global intangible

low-taxed income tax, or Gilti, serves to set a floor on the tax

companies pay on foreign income, whether to U.S. or foreign tax

authorities. In effect, multinational companies that pay less than

a minimum 10.5% to foreign jurisdictions on foreign income must

make up the difference to the IRS. That minimum tax is applied to

foreign income over a threshold based on the company's foreign

tangible assets. The idea: Income over that threshold is more

likely to be generated by patents, trademarks and other

intellectual property easily stashed in low-tax havens.

Some companies have been struggling with Gilti and warning that

its interactions with pre-existing tax laws mean they may pay the

U.S. even though they are already paying substantial foreign

taxes.

Investors can expect guardrails to mostly affect large companies

that have successfully pushed their tax rates down by housing

intellectual property in low-tax jurisdictions such as Ireland or

Luxembourg. Foreign companies are particularly wary of the BEAT.

Foreign banks, too, face exposure, although the rules put forward

by the Treasury late last year provided a measure of relief.

The legislation's international provisions also offer a tax cut

for U.S. companies that sell their goods or services overseas,

generating what the law dubs foreign-derived intangible income. The

provision provides a deduction for foreign sales of U.S.-produced

goods and services above a threshold based on the company's

tangible assets, effectively bringing tax on that income down to

13.125%.

Few companies have yet disclosed how they expect the provision

to affect them, however, and the effective tax rate on such income

rises to 16.4% in 2025. That, plus the risk of challenges from

foreign countries calling the measure an unfair trade subsidy,

leaves it unclear how likely companies are to change their

operations to benefit from the provision.

Glassmaker Corning Inc. says its tax rate will rise to between

20% and 22%, from a core rate of about 17% in 2017, in part because

of the international provisions.

Foreign companies are particularly wary of the BEAT. Swiss

chemical manufacturer Clariant International Ltd. says it expects

to pay millions more in taxes to the U.S. because of it, though the

company also expects to benefit from the lower U.S. corporate tax

rate.

Write to Theo Francis at theo.francis@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 15, 2019 08:14 ET (13:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

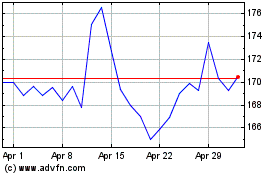

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

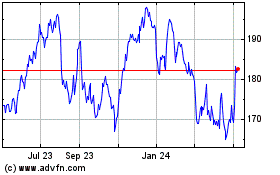

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024