By Denise Roland

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (November 20, 2018).

Novartis AG's recent acquisition streak is pivoting the company

toward new treatments that bear little resemblance to traditional

drugs.

The Swiss company has spent nearly $15 billion in the past year

to build its presence in cutting-edge areas of medical research,

including gene therapy, or treatments that introduce new DNA into

the body, and radiopharmaceuticals, which are drugs that carry

radioactive particles to tumors for close-range radiotherapy.

The deals build on Novartis's early move into a new form of

cancer therapy known as CAR-T, and underscore new Chief Executive

Vas Narasimhan's ambition to get ahead on innovative therapies that

he believes will drive significant future growth.

"We thought if we could gain a leadership position it'd be

harder for competition to take us on," Dr. Narasimhan, who led drug

development at Novartis before becoming CEO, said in an interview.

The 42-year-old Harvard-trained doctor said at a recent investor

event that he hopes such therapies will generate a fifth of

Novartis's revenue within five years. Currently, they are a tiny

fraction of its $49 billion in yearly sales.

The new treatments pose challenges. The jury is still out on how

gene therapies, which potentially offer one-time cures for

previously untreatable diseases, should be priced.

Radiopharmaceuticals are logistically challenging to deliver

because of the short half-life of the radioactive component.

Dr. Narasimhan acknowledged at the event that risks were higher

than with conventional drugs but added that "there's a risk in not

pushing into new technologies and new areas of science to find

breakthrough medicines."

In October last year, Novartis paid $3.9 billion for Advanced

Accelerator Applications, which makes a radiopharmaceutical for a

rare form of gut and pancreas cancer. Last month, it said it would

pay $2.1 billion for radiopharmaceutical specialist Endocyte Inc.,

which targets prostate cancer.

In April, it bought AveXis Inc., which is developing a gene

therapy aimed at a fatal infant muscle-wasting disease, for $8.7

billion. Novartis also struck a licensing deal in January giving it

the right to sell Spark Therapeutic Inc.'s gene therapy for a rare

eye disorder in Europe and other markets outside the U.S.

None of the new acquisitions are likely to generate a fast

return for Novartis. The therapy by Endocyte is still under

development. Meanwhile, the AveXis gene therapy is in the hands of

regulators, with a decision expected in the first half of next

year. AAA's radiopharmaceutical and Spark's gene therapy both

target rare conditions, with modest potential markets.

But they do position Novartis as a potential leader in these

areas: Today, just one gene therapy, Spark's Luxturna, and a

handful of radiopharmaceutical treatments, one of them Novartis's,

are available in the U.S.

Gene therapy is a fast-expanding area, with around 180 clinical

trials under way in the U.S. alone, according to Datamonitor

Healthcare. Novartis was the first to get U.S. approval for a

high-tech therapy known as CAR-T, where disease-fighting white

blood cells are removed from a patient, genetically modified to

enhance their cancer-fighting ability, and reinfused into the body.

Trials show its product, called Kymriah, improves survival rates

for certain forms of hard-to-treat blood cancer and typically only

needs to be given once.

"CAR-T made us start to think of things differently," said Liz

Barrett, head of Novartis Oncology. "Do you want to be in the world

of introducing incrementally better medicines" when "payers have a

much higher bar for what's reimbursed?"

Still, Novartis's experience with Kymriah underscores the

challenges associated with selling expensive medicines at a time

when drug pricing is attracting political scrutiny. Its price tag

of up to $475,000 per patient has attracted criticism from patient

groups. Novartis says its pricing is responsible, pointing to

independent studies that show Kymriah could command a price of

$600,000 to $750,000.

The high cost of Kymriah and the other currently available

CAR-T, Gilead Sciences Inc.'s Yescarta, is putting pressure on

hospitals, which in some cases lose money by offering the therapy,

says Joanna Hiatt Kim, vice president for payment policy at the

American Hospital Association. For now, many hospitals are

absorbing the cost because the number of patients is small, said

Ms. Kim. But as more such therapies become available, price is

likely to become a bigger sticking point.

"If you're losing $200,000 to $300,000 per case, there's simply

so many times you can do that," she said.

Novartis's move into gene therapy is likely to bring more

pricing controversy. The only gene therapy currently available in

the U.S. -- Spark's Luxturna -- costs $850,000 per patient, raising

questions about how health systems will be able to pay for such

treatments as they become more common.

"The economics of developing a drug are becoming much more

challenging," said Ed Schoonveld, pricing and market access expert

at health care consulting firm ZS Associates. Existing payment

models aren't set up to handle the high prices of the one-time

cures that gene therapies typically provide, he said.

Novartis says its leading gene therapy would be cost-effective

at $4 million a patient. While that would mean a high upfront cost,

the company says it would be in line with less expensive medicines

that need to be taken repeatedly. Novartis has yet to decide

pricing, and is conscious of potential push back.

"The media will put our one-day sticker price in the headline

without educating society that this is actually great value," Dr.

Narasimhan said. "We're giving a lifetime benefit."

To pre-empt pricing issues, Novartis is talking with some

insurers about different ways to pay, such as in installments or

depending on how well patients respond to therapy.

Still, such models also throw up problems. Novartis already

offers an outcome-based pricing option for Kymriah where it only

gets paid if patients are doing well 30 days after treatment. But

hospitals have questioned whether that time frame is appropriate

for assessing success, according to the AHA's Ms. Kim. The merit of

paying in installments is also challenged when a patient dies

before the treatment has been paid off.

Radiopharmaceuticals don't present the same pricing

difficulties. Lutathera, at $190,000 for a standard four-dose

course, is more in line with other new cancer drugs, according to

Novartis's Ms. Barrett.

But they are complex to produce. The radioactive component only

lasts about 72 hours, meaning they need to be made on demand and

sent quickly to the hospital that needs them.

Ms. Barrett said Lutathera's early commercial success -- it went

on sale in July -- was in part due to the company "working very

closely with institutions in making the logistics as easy as

possible."

While Novartis's strategy involves taking on some risk, its

first-mover role could play to its advantage, according to Dan

Mahony, a fund manager at Polar Capital LLC, which holds Novartis

stock. "That initial foray doesn't make them much money," he said,

"but it teaches them about how the market will work."

Write to Denise Roland at Denise.Roland@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 20, 2018 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

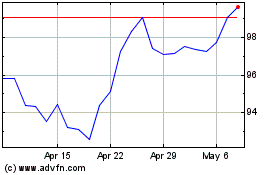

Novartis (NYSE:NVS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

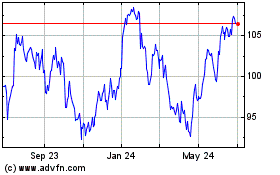

Novartis (NYSE:NVS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024