By Leslie Scism

When Nicole Herivaux was born at Coney Island Hospital in New

York in 1980, doctors made a mistake that left one of her arms

useless.

Ms. Herivaux's family sued and reached a settlement on the

infant's behalf. It provided $2,200-a-month in lifetime income paid

out by an insurance firm, and lump sums of as much as $200,000 were

sprinkled in to help, say, with college costs.

This money was supposed to be paid into specified banks until

Ms. Herivaux was 18, with court approval needed for its spending.

But according to a lawsuit in a New York state court, MetLife Inc.

mistakenly began sending checks directly to her mother when Nicole

was 15, and her mother passed on to Nicole just a portion of the

proceeds from thereon.

The suit alleges the mother hid from her daughter the full size

of the settlement. Now 37, Nicole lives in a cheap apartment in

Detroit, has $30,000 in student debt and sometimes relies on

free-food pantries.

"I could have done so many different things with my life" had

she received the full proceeds, Ms. Herivaux said in an

interview.

Her mother, Marie Herivaux, didn't respond to repeated efforts

to contact her.

MetLife suspended payments on the annuity last year after the

litigation began and says in court filings it will dispatch the

money to the younger Ms. Herivaux if the court tells it to do so.

MetLife declined to comment.

In its filings, MetLife is seeking to get the lawsuit dismissed

for reasons including that it wasn't party to the original

transaction in 1983. It assumed responsibility for the

structured-settlement annuity in a 1995 transaction. MetLife also

maintains no evidence has been introduced that it ever was

instructed to directly pay Nicole Herivaux.

Ms. Herivaux's lawyer David Jaroslawicz says the 1983 court

order and settlement are clear enough that the money was intended

for Nicole. MetLife is to file more responses this week.

The lawsuit is the latest example of an unexpected problem

popping up at MetLife from decades-old business. The suit has been

unfolding in a New York County courthouse as the company has

publicly acknowledged failing to pay benefits to 13,500 retirees in

its business of taking on responsibility for private-sector pension

plans. Some of those payments date to the 1990s.

MetLife has said it failed to aggressively search for people as

they neared pension-eligibility age. The 13,500 represent about 2%

of the 600,000 retirees in MetLife's pension-risk-transfer

business.

Earlier, in 2012, MetLife was one of many insurers to settle

multistate regulatory probes into unclaimed death benefits. Some of

those policies were issued in the early 1900s. MetLife didn't admit

any wrongdoing and emphasized that the overdue policies represented

only a tiny fraction of its policy count.

Industry analysts and consultants say it is understandable that

MetLife would have mistakes lurking in older business, because

there is so much of that on its books as a company tracing its

roots to the 1860s. Improved technology makes widespread errors

less likely on newer business at MetLife and elsewhere, they

say.

The pension matter prompted a global review focused on other

potential unclaimed property and missing participants. On Feb. 14,

MetLife Chief Executive Steven Kandarian told analysts he doesn't

believe any significant problems of that type remain. "We made sure

we had the resources within countries and regions to put all

necessary people against this review to get to the right answers,"

he said.

The use of structured-settlement annuities to resolve injury

cases such as Ms. Herivaux's, grew dramatically in the 1980s.

Lawyers representing injured minors often prefer them for paying

out large settlements in medical-malpractice and catastrophic

accidents. The money often is routed through a guardian until the

person turns 18.

Peter Arnold, who runs a consulting group in Washington that

advises on structured settlements, said a settlement typically

spells out what happens when the child turns 18, and if it isn't

clear, that can be a point of contention.

Before MetLife entered the scene in Ms. Herivaux's instance,

payments were deposited in banks in the name of her mother "as

guardian," according to filings for New York City and the New York

City Health and Hospitals Corp., which are being sued along with

MetLife. Between 1984 and July 1995 the court approved withdrawals

for such things as medical and living expenses, private-school

tuition, and the 1991 purchase of a Florida home for $140,828, in

Nicole's name, filings show.

After MetLife took responsibility for the annuity, "the proper

payee mysteriously changed," the city's filings state. The city

maintains it properly obtained the annuity in 1983 and opposes

MetLife's effort to dismiss the lawsuit.

Several years ago, Nicole spotted a $2,200 MetLife check made

out to her mother, and she began putting the pieces together, she

alleges in court. She tracked down the lawyer who handled the 1983

medical-malpractice lawsuit.

"It was just incredible to me" that Nicole hadn't been getting

all of the money, said the lawyer, Michael Wolin, who had last seen

her as an infant. "Especially when she told me of the financial

hardships."

In years past, Nicole said she had sometimes borrowed from her

mother. "The ironic thing was I was paying back myself," she

said.

Write to Leslie Scism at leslie.scism@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 21, 2018 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

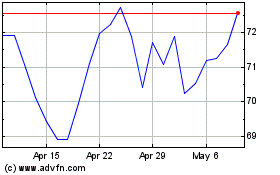

MetLife (NYSE:MET)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

MetLife (NYSE:MET)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024