By Deepa Seetharaman in San Francisco and Sam Schechner in Paris

PARIS -- Facebook Inc. says it has ramped up efforts to curb

misinformation, including removing accounts and labeling fake news.

But video and images disseminating fake news are increasing faster,

alongside delays in accrediting Facebook's fact-checking

partners.

Facebook this week said it has vetted more than 30,000 accounts

in France ahead of the country's presidential election to determine

if they are fake, partly in response to what security officials say

is a wave of social media misinformation aimed at disrupting

Western elections.

Suspicious accounts were subject to verification, with the aim

of cutting off the biggest spreaders of spam and trolling as well

as fake news, a spokeswoman said Friday. The company has said it is

targeting "the worst of the worst" offenders.

But the disclosure raised questions about how swiftly and

effectively Facebook has moved to address widespread criticism of

its handling of fake news during the U.S. election. "Facebook

hasn't really expressed what it wants to take down. What is the

worst of the worst?" said Alexios Mantzarlis, head of the

International Fact-Checking Network, affiliated with the Poynter

Institute, which Facebook has put in charge of vetting groups

before they can fact check. "We need a much clearer

methodology."

In the run-up to the first round of the French election on April

23, the spread of fake news has accelerated. The 30 most-popular

fake or misleading articles on hot-button political topics were

shared roughly 900,000 times in the last two months, compared with

650,000 times in December and January, according to an official in

the French president's office.

The 30,000 vetted accounts are a small portion of Facebook's 25

million daily active accounts in France. The company didn't say how

many of the accounts shared fake news, or how many such accounts

they normally remove every year. But social media experts say even

a small number of fake accounts can, if properly organized, play an

important role in amplifying disinformation, increasing the chances

real users will pick up on them and spread them.

The prevalence of fake news during the French presidential race

reveals the inherent struggle facing tech companies such as

Facebook and Alphabet Inc.'s Google that try to police fake news

across a continent, where language, media landscape and electoral

politics vary dramatically from country to country. Across the

border in Germany, where elections are scheduled for September, the

government has proposed a new bill that could impose fines of up to

EUR50 million on social networks that fail to delete hate speech or

fake news.

Facebook, in particular, is adamant it doesn't want to play the

role of "arbiters of truth," as Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg

calls it. The Menlo Park, Calif., company faced intense criticism

after the 2016 U.S. presidential election for allowing fabricated

and made-up news articles to spread unchecked on its platform, such

as a story stating that the pope endorsed Donald Trump. Mr.

Zuckerberg initially dismissed those concerns, but later

acknowledged Facebook must find a way to prevent misinformation

from going viral and announced a series of changes to its

approach.

Many of the fake news stories in France have an anti-immigrant

agenda, experts say, playing into a highly contentious election

that has become a referendum on the continent's future. Buffeted by

a string of terror attacks and recent allegations of Russian

hacking, the leading contenders to become the country's next

president are pro-European Union candidate Emmanuel Macron and

Marine Le Pen, the leader of the anti-immigrant National Front who

wants to withdraw France from the EU and its common currency.

One video posted by a page called "SOS Anti-White Racism," which

was viewed more than 15 million times on Facebook since its posting

on March 18, showed a man assaulting two women in a hospital. The

accompanying French-language post implied the attacker was a

migrant to France, saying, "We take them into our country...how

grateful they are." But Russian media had previously reported the

assault happened at a hospital in Russia in February. Facebook

removed the page that hosted the video within the last day.

A Wall Street Journal review of about a dozen news items

identified as false by French news organizations in the last month

shows they were liked, shared and retweeted at least 487,000 times

on social media, and shared by pages with as many as 930,000

followers on Facebook, according to the social-media monitoring

service CrowdTangle.

In December, Facebook said it had identified several markers of

sites that spread fake news and it would demote those in the news

feed. The removal of some French sites used the same improvements

to the algorithm, which comb the platform for accounts that, for

instance, repeatedly post the same content or suddenly become

active. Facebook has said it estimates fewer than 1% of its 1.86

billion monthly active accounts aren't authentic.

Facebook also said in December it would outsource the delicate

task of determining what stories are true or false to five external

organizations in the U.S., all associated with Poynter, which can

mark certain stories as disputed after enough users flag them. If

two or more groups agree a post is false, it carries a "disputed"

tag on Facebook and appear lower in users' feeds.

So far this year, Facebook has partnered with 11 fact-checking

organizations in France, Germany and the Netherlands to help slow

the spread of misinformation on its platform, an extension of the

U.S. program.

In France, only one organization -- the French daily newspaper

Libération -- has obtained the requirements necessary to mark posts

as disputed, according to the International Fact-Checking

Network.

Facebook decided to allow French fact-checkers to use the

disputed tag before receiving approval because the verification

process was taking longer than expected, a person familiar with the

matter said.

But purveyors of fake news providers are managing to stay one

step ahead of Facebook. Facebook only shows its fact-checking

partners posts containing links to fake news stories. Much of the

fake news being shared uses photos and videos embedded in posts,

researchers say. That lets them dodge Facebook's software, which

doesn't yet surface videos and images, according to Facebook and

fact-checkers. Facebook plans to adapt its software to videos and

images, according to a person close to the company.

"The most effective misinformation is presented in a visual

form. That's what's going to travel fastest," said Jenni Sargent,

director of First Draft News, a nonprofit that is running a

Google-backed program to fact check widely shared claims in the

French election.

Still, policing what qualifies as fake can be tricky in any

medium. The French far-right website La Gauche m'a Tuer was cited

by French news organizations that perform fact checking for sharing

on Facebook what they described as a "false" story saying the EU

was lending money to buy hotels for migrants. The story remains on

Facebook. Mike Borowski, the editor of the site, says his stories

aren't fake, but rather opinionated takes on facts reported

elsewhere.

Mr. Borowski says fact checking is just a way for mainstream

media organizations to denigrate new competition. "They are losing

market share because of sites like mine," he says. Fact checking

"is just a new way to censor."

Write to Deepa Seetharaman at Deepa.Seetharaman@wsj.com and Sam

Schechner at sam.schechner@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 14, 2017 20:26 ET (00:26 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

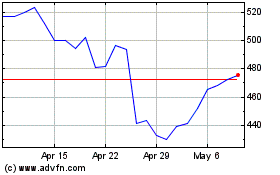

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024