By Telis Demos

Global trade tensions have been good for banks in the business

of global trade.

Banks' revenues from financing cross-border commerce are in the

best shape in years, despite President Trump's threats of Mexican

tariffs, stalled progress on a U.S.-China accord and Britain's

impending exit from the European Union without a trade deal.

Trade-finance revenue at a group of the world's biggest banks

ticked slightly higher to $5.8 billion last year, the first time in

six years it didn't fall, and is on track to grow further in 2019,

according to Coalition, a banking-industry data tracker.

Among the leaders in trade finance is Citigroup Inc. The bank

has said alternative trade routes are growing, especially in Asia,

following the imposition of new tariffs between the U.S. and

China.

"What used to be super efficient has become inefficient," said

John Ahearn, global head of trade at Citigroup. "The opportunity

for banks is our ability to finance inefficiencies in the supply

chain."

Trade tensions have spurred demand for banks' services as

intermediaries in the cross-border movements of goods and services.

Banks make money fronting cash or offering payment guarantees to

companies when they are making overseas sales or purchases.

In times of trade peace, companies do business directly with

each other and don't feel the need to insure against a lot of risk.

But when a tariff makes a company's usual trade partners too

expensive, or political risk makes dealing with them untenable,

they turn to banks to provide payment guarantees or help them

establish new trade routes.

A U.S. farmer hit by tariffs on sales of soybeans to China, for

example, might seek a bank's help to finance sales to Brazil or

Argentina, instead.

Still, for banks, there is a big difference between trade

skirmishes and trade wars. While low-level conflict may spur

activity in some parts of their businesses, an all-out war that

results in sharp declines in commerce and economic growth would

erase any gains -- and then some.

"When risk is higher, banks price higher," said Eric Li,

research director at Coalition. "But if we have full-blown trade

war, there are bigger problems."

In addition to Citigroup, the biggest players in trade finance

are BNP Paribas SA, Credit Agricole SA and HSBC Holdings PLC,

according to Coalition. Bank of America Corp., Deutsche Bank AG,

JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Standard Chartered PLC also do healthy

business in trade finance.

There is a number of factors behind this stabilization of

trade-finance revenue. For one, rising oil prices have made

financing of cross-border commodities sales more lucrative. Banks

charge based on the dollar amounts they finance or guarantee, so

they earn more as prices rise.

The Federal Reserve's easing of monetary stimulus has made

dollars more scarce in many parts of the globe, allowing banks to

charge more to companies that want to borrow in dollars or sell

other currencies for dollars.

Banks also can benefit when companies in different countries

need to find new ways and places to move goods during trade

disputes. For example, expensive tariffs could spur a Chinese

company to bypass the U.S. and sell to a company in another Asian

country, instead.

Citigroup's client revenue from China-based companies doing

business in other countries in Asia rose more than 22% between

November 2017 and November 2018, the bank reported recently.

For the past several years, many companies have opted to trade

with each other directly, on so-called open accounts, without a

bank guaranteeing payment. But the advent of tariffs has made some

companies rethink this approach, especially those trading with new

partners or in new countries.

"After years of doing business together, you're used to payments

being made on time, just like individuals build up credit history

and a trusted relationship," said Patricia Gomes, regional head of

global trade and receivables finance at HSBC in the U.S. "But new

partners don't have that trust, and aren't going to extend payment

terms without a bank guarantee backing that up."

Among those guarantees by banks are so-called letters of credit.

The value of letters of credit grew to $2.5 trillion in 2018 from

$2.3 trillion the prior year, according to data drawn from

transactions via SWIFT, the global banking network. Industry

veterans say that, based on typical prices for these credits, the

jump translated into nearly a billion dollars in additional revenue

globally for banks.

The increasing riskiness of these guarantees has allowed banks

to charge more for them. For years, when companies weren't willing

to pay much for trade finance, banks would provide it at a loss in

the hopes of securing more lucrative business in the future.

Banks now are actively seeking out new customers, including some

with less-than-perfect credit that they might have avoided in the

past, said Coalition's Mr. Li.

Write to Telis Demos at telis.demos@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 09, 2019 11:10 ET (15:10 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

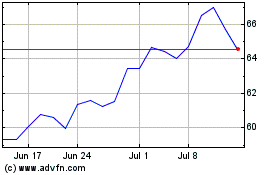

Citigroup (NYSE:C)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Citigroup (NYSE:C)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024