With its Shanghai factory and a new sales record, Tesla is

finally meeting its deadlines. That's welcome news for disruptors

after a rough year.

By John D. Stoll

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (January 4, 2020).

The excitement over Carlos Ghosn's escape to Lebanon from Japan

may have obscured an equally impressive feat in the car business.

Tesla Inc. is meeting its targets.

The electric-car maker said Monday its Shanghai plant is

building 1,000 Model 3 sedans a week. That's less than a year after

Chief Executive Elon Musk stood in an empty 210-acre field and

declared this factory would go up in "record time." And on Friday,

Tesla said it set another annual sales record and exceeded Mr.

Musk's ambitious goal of selling 360,000 vehicles for the year.

This Shanghai production achievement matters to a broader auto

industry struggling to go global, succeed in the Chinese market,

and go electric. But this latest "gigafactory" and the surpassing

of its 2019 sales target also raise an important prospect. If Mr.

Musk starts hitting his targets with regularity, Tesla will quickly

go from interesting phenomenon to major industry player.

Shareholders were feeling good about Tesla even before this

week's news. After slumping much of last year amid profitability

concerns and Mr. Musk's battles with regulators, shares surged 74%

in the fourth quarter. On Friday, they rose as much as 5.5% to hit

an all-time high of $454 after the release of the latest sales

numbers, which showed that Tesla is now outpacing brands like

Porsche, Chrysler and Lincoln and roughly on par with sales of

Cadillac. And Tesla's roughly $80 billion market capitalization far

exceeds the value of its Detroit rivals.

I asked Mr. Musk if he'd be up for doing a victory lap. He

demurred because it is "bad karma."

I'll take the lap for him: Tesla's win is a win for the

disruptor. After a tough year in startup land, Elon Musk -- the

patron saint of any entrepreneur looking to make big bucks by

questioning the status quo -- has done a mic drop.

This follows a year that proved the path ahead for Silicon

Valley won't be smooth. We had lackluster initial public offerings

of many so-called unicorns (think Uber Technologies Inc., Lyft Inc.

or Slack Technologies Inc.), irrational exuberance for WeWork and

growing demand that startups stop giving away the store and start

generating black ink.

Mr. Musk knows well this bumpy road, and that it is navigable.

Any analysis of Mr. Musk is incomplete without mentioning his

reputation for missing the mark on lofty projections. He's aware of

it. When predicting last April that Tesla would have autonomous

robotaxis in 2020, he warned his forecast faces this "only

criticism -- and it's a fair one -- sometimes I'm not on time."

To be even fairer, the broken-promises problem is an

auto-industry problem. General Motors Co. has failed to meet

electric-vehicle targets; Ford Motor Co. widely missed projections

for a Lincoln luxury-brand revival; Volkswagen AG repeatedly missed

forecasts for U.S. market share gains. Let's not get into all the

autonomous-vehicle goals that will go unmet.

Still, people who are habitually late have damaged credibility,

and the 48-year-old Mr. Musk is no different.

After his Model 3 came out in 2017, Detroit auto executives

loved to point out that sure it's a great car, but it was late to

the market, pricier than expected and available in lower volumes

than initially promised. Many executives and automotive journalists

privately snickered, "See, Elon, making cars is actually pretty

hard."

I geek out on Tesla but also succumbed to skepticism.

Consider this conversation with my son and his 13-year-old

friends over Christmas break. The car nut among them, Sam, asked me

when I get to bring home Mr. Musk's "killer" Cybertruck, a pickup

he aims to launch by 2021. I laughed and said, "You'll be in

college, kid." I've since questioned that math, however, after

reading about the Shanghai factory.

Cybertrucks, gigafactories and volume projections represent

something deeper going on at Tesla and startups following its wake.

The struggle to get big enough fast enough without going broke is

as core to the entrepreneurial experience as hoodies and ping-pong

tables.

Tesla has for 17 years been chasing adequate bigness, or scale,

in an industry too big for its own good. Ford, GM, and Mr. Ghosn's

former employer, Nissan Motor Co., are all cutting jobs, shrinking

global footprints and cutting out major portions of their product

lines. The fever to grow at Tesla, meanwhile, is so hot that Mr.

Musk built tents at an older factory in Fremont, Calif., to more

quickly fulfill orders.

The Shanghai project went off without a hitch by comparison.

"It was a phenomenal accomplishment by any measure," Michael

Dunne, a consultant on China's auto industry, told me this week.

"They clearly applied a lot of lessons learned from their fraught

ramp-up in Fremont."

Tesla now aims to replicate that success at a factory planned in

southeast Berlin. It's unclear if Mr. Musk will enjoy the same

support from workers, suppliers and government officials in Germany

as he did in Shanghai. If he succeeds, he'll supercharge his

ambition to build 1 million cars annually, and break into the ranks

of big-volume auto makers.

Robert Sutton, a management professor at Stanford University,

calls this seemingly never-ending quest to scale up as "the problem

of more." While there are several definitions of what it means to

chase scale, "it comes down to the difficulty of spreading

something good from those who have it to those who don't -- or at

least not yet."

Mr. Sutton notes Starbucks Corp. and Domino's Pizza Inc. both

suffered during "fast and sloppy" attempts to ramp up. Both firms

eventually mastered those issues and set new standards for the

fast-food industry.

Today, we associate "the problem of more" with startups. Last

year, when I went to Alaska on a networking trip with about a dozen

founders of companies working on ocean-sustainability issues, I saw

this first hand.

I took in the Northern Lights with Chelsea Briganti, co-founder

of Loliware, for instance. Her edible seaweed cups and straws made

waves on CNBC's "Shark Tank," earning a healthy dose of working

capital and publicity. These products are in growing demand as

trendy bars look to offer sustainable products and other

establishments respond to regulation of plastic products.

Ramping up production and distribution at a manufacturing

company fast enough to please investors, suppliers and customers

ain't easy -- just ask Elon. For Ms. Briganti, going from a few

million straws in annual production to many, many millions requires

money that doesn't exactly grow in an underwater kelp forest.

For entrepreneurs like her, it's wise to pay attention to Mr.

Musk's words that followed his acknowledgment that he's not always

on time. "But, I get it done," he said. It sometimes takes building

a China factory in under a year to prove that.

Write to John D. Stoll at john.stoll@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 04, 2020 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

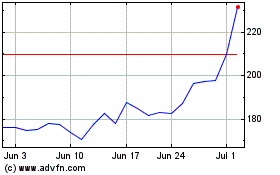

Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Tesla (NASDAQ:TSLA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024