An Antitrust Case That Feels Stuck in the Past -- WSJ

March 22 2018 - 3:02AM

Dow Jones News

By Greg Ip

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (March 22, 2018).

In the 17 months since AT&T Inc. and Time Warner Inc.

announced their merger, here is what their internet rivals have

been up to: Amazon.com Inc. won three Oscars, Hulu won the coveted

Emmy for best drama, Netflix Inc.'s market value surpassed Time

Warner's, and Facebook Inc. was ensnared in an electoral

manipulation probe.

You wouldn't know this from lawsuit the Trump administration has

filed to stop the AT&T-Time Warner merger. The suit, which went

to trial this week, seems conceived in a world before the internet

became a gigantic petri dish for video content.

This isn't a trivial omission. At the heart of every antitrust

case is the potential for a company to hurt its competitors and

consumers through its dominance of a market. If old media such as

Time Warner ever possessed such power, it is ebbing fast as the

clout of new media grows.

The Justice Department will win if it can persuade the court

that the merger's effect is "significantly to lessen competition,"

an inherently uncertain and subjective judgment. Yet the economic

test is more straightforward: For AT&T to exercise monopoly

power in the sale of content such as HBO and CNN, alternative

suppliers of content must face steep barriers. Those barriers are

falling.

Since 2005, University of Minnesota economist Joel Waldfogel has

shown, plunging prices for high-end digital cameras slashed the

cost of producing high-quality filmed entertainment, leading to an

explosion in the volume of new movies with no loss of quality.

Meanwhile broadband internet has provided a distribution

alternative to movie studios, television networks and cable. Since

2009, the number of original scripted series produced by online

houses such as Amazon, Netflix and Hulu has soared from one to 117,

now accounting for a quarter of all U.S. studio-produced

series.

Online video is also quite "sticky": Subscribers spend an

average of 124 minutes a day on Netflix, compared with 96 minutes

on Comcast properties (including NBC) and 46 minutes on Time Warner

channels, according to Steven Cahall and Mark Mahaney, analysts at

RBC Capital Markets.

They attribute this in part to their relatively high quality:

For every dollar of customer revenue, Netflix spends twice as much

on content as its next closest competitor. The analysts conclude

Netflix has plenty of room to raise prices. The stock market seems

to agree: In 2009 Netflix, then mostly still a distributor of disks

by mail, was worth 8% as much as Time Warner in 2009; it's now

worth 84% more.

The Justice Department argues that a combined AT&T-Time

Warner will have both the incentive and the ability to charge rival

distributors, both traditional and internet-based, more by

threatening to withhold content. AT&T says this is ridiculous:

Cutting off other distributors would cost it dearly in lost

revenue, and its leverage is minimal, because "an expanding array

of content sources" means no content is "genuinely essential for

any given distributor."

The Justice Department largely dismisses that prospect. Such

mistrust of free-market dynamism is unusual in a Republican

administration, particularly one that prides itself on taking the

shackles off business. It is also strikingly at odds with the

Justice Department's fellow Trump appointees at the Federal

Communications Commission. Last year the FCC rolled back "net

neutrality" rules that had barred internet providers from charging

more for faster access to their networks.

The commission concluded that net neutrality discourages

internet providers from experimenting with different business

models or expanding broadband capacity. That is what the antitrust

suit may do, if AT&T's rationale for the merger is taken at

face value. By delivering its content over AT&T's wireless

network, Time Warner would, as Amazon and Netflix now do, gain

valuable insight into subscribers, which it can use to improve its

offerings. That isn't feasible with Time Warner's existing model,

AT&T says.

"AT&T's overriding economic objective is to encourage

consumers to use its networks, no matter whose programs they

watch," the company adds. If owning Time Warner accomplishes that,

its network becomes more valuable -- and encourages it to

expand.

More than just economics, of course, hangs over this trial.

President Donald Trump, no fan of CNN, opposes the merger for, he

says, concentrating too much media power in too few hands. The

Justice Department says that played no role in its decision to sue,

but the claim still resonates, on the right and on the left.

Yet blocking mergers to preserve political diversity gets dicey

fast: Whose voices should be preserved? What degree of

cross-ownership is permissible: should Verizon Communications Inc.

be allowed to own Yahoo, or Walt Disney Co. to control

FiveThirtyEight? What if cross-ownership preserves otherwise

financially fragile political voices?

If you're worried about monopoly power over political speech,

there may be more fruitful places to look. According to the Pew

Research Center, 43% of Americans get their news from social media

and news apps, more than do from network, local or cable

television. Online platforms like Google and Facebook are closer to

monopolies than any old media counterpart. And as the revelations

over the use of Facebook data in political campaigns shows, they

can be weaponized in ways television never was.

Write to Greg Ip at greg.ip@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 22, 2018 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

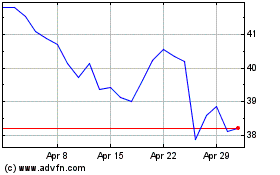

Comcast (NASDAQ:CMCSA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

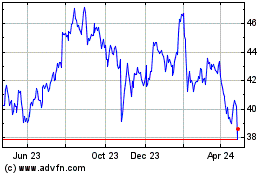

Comcast (NASDAQ:CMCSA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024