UNITED

STATES

SECURITIES

AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

WASHINGTON,

D.C. 20549

SCHEDULE

14A

(Rule 14a-101)

INFORMATION REQUIRED IN PROXY STATEMENT

SCHEDULE 14A INFORMATION

Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a)

of the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934

| Filed by the Registrant |

☒ |

| Filed by a Party other than the Registrant |

☐ |

Check the appropriate box:

☐

Preliminary Proxy Statement

☐

Confidential, for Use of the Commission only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2))

☐

Definitive Proxy Statement

☒

Definitive Additional Materials

☐

Soliciting Material Pursuant to §240.14a-12

RENOVARO

BIOSCIENCES INC.

(Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter)

(Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if

Other Than the Registrant)

Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box):

| ☒ |

No fee required. |

| ☐ |

Fee paid previously with preliminary materials: |

| ☐ |

Fee computed on table in exhibit required by Item 25(b) per Exchange Act Rules 14a–6(i)(1) and 0–11 |

The following is a transcript of the interview between Dr. Mark

Dybul, Chief Executive Officer of Renovaro Biosciences Inc. (NASDAQ:RENB) (“Renovaro”) and The Business of Biotech

Podcast, which was published on December 11, 2023. While effort has been made to provide an accurate transcription, there may be

typographical mistakes, inaudible statements, errors, omissions or inaccuracies in the transcript. Renovaro believes that none

of these are material.

Matt Pillar: If you told me that Dr.

Mark Dybul ever back down from a public health challenge or any challenge for that matter, you’d have to bring some very

hard evidence to convince me of it. He’s the guy who earned his place on the global stage running point on AIDS relief in

a presidentially appointed position during the mid-2000s after his early career was dedicated to AIDS research and clinical care.

He’s faculty co director at the Center for Global Health and quality, a professor in the Department of Medicine at Georgetown

University Medical Center and was the executive director of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. He’s

also the biotech entrepreneur currently leading Renovaro Biosciences, a company developing therapeutic vaccines and therapies in

oncology, HIV and hepatitis and one that seen its own share of very unique challenges from leadership change to the integration

of cutting edge AI technology and more challenges Dr. Dybul has steadfastly navigated. I’m Matt Pillar, this is The Business

of Biotech and I admit that there’s a lot of detail to be filled in there, but I’m thrilled to welcome just a man to

do it, the Honorable Dr. Mark Dybul himself. Dr. Dybul, thank you for joining me. It’s truly an honor and welcome to the

show.

Mark Dybul: Thank you. It’s

great to be with you, Matt. Thanks for inviting me.

Matt Pillar: My pleasure. We have

a lot to cover. But I want to get started by rewinding like going way back, rewinding the clock quite a bit. I want to kind of

get a feel for your professional trajectory. So way back when you were in your undergrad and contemplating post grad studies, what

was it that inspired you to pursue an MD?

Mark Dybul: That’s a great question,

especially because I began trying to decide between a doctoral degree in philosophy or theology and didn’t take any science

classes as an undergrad. I read an article—it’s not a career path necessarily to recommend anyone and not do any more.

And then I read an article about HIV in Africa and it just kind of consumed me and decided that I needed to shift and spend my

life fighting HIV, and going to medical school seemed like you’re—basically you become an advocate or you go to medical

school, and if you go into medicine, you can do both. You can be an advocate and do the medicine. So I decided to go in that direction.

So I went to medical school specifically to join the fight against HIV. At the time, everyone was dying. I did my fourth year of

medical school in San Francisco, holding the hands of 17 year old dying alone, because their friends and family wouldn’t

visit them. And for those who lived through that in the United States, if you go to Africa—went to Africa at the time—that

horror was compounded a thousand fold in ways that is almost indescribable, so I changed my career path and went into research.

Matt Pillar: What year was that? Sorry

to interrupt you.

Mark Dybul: No, no problem at all.

I went to medical school in 1988. I graduated in 92, then did my residency in the University of Chicago in internal medicine then

and a fellowship in infectious diseases at the National Institutes of Health. Now the National Institutes of Health is somewhat

unique when you’re accepted into a fellowship, you’re actually accepted into a laboratory. You do your clinical time,

but you’re already accepted to go into a lab after your first year. That lab happened to be Tony Fauci’s, so I met

Tony in 1994 and then was accepted into his lab and started work with him. And we were doing work on basic immunology, virology.

My first supervisor was Drew Weissman who just won the Nobel Prize for the COVID vaccine. And I’ve stayed in touch with Drew,

he is an amazing scientist and a person as is Tony. And then I was running a section of Tony’s lab, immunology virology.

We were doing work in Africa, studying antiretroviral therapy in Africans, when President Bush had the bold idea to do something

huge on HIV globally. He turned to Tony as any sensible president would. Tony and I were doing the work in Africa. So I got involved

with creating with a very small group in the White House. Tony and I were the only outside what became the President’s Emergency

Plan for AIDS Relief, which I was then asked to run. As a senate-confirmed appointee, I was still a civil servant, but in a political

job. And that program grew from zero budget and eight people in the basement of the State Department to $6.5B dollars a year. It’s

now saved over 25 million lives. So it was building a startup in the US government, which is not the easiest thing in the world

to do.

Matt Pillar: No like I like I said

Dr. Mark Dybul is not one to back down from a challenge. I want to—before we get into that you fast forward a little bit

beyond where I wanted to go. I wanted to get a sense for the early work that you did in your academic years. Obviously, that was

a completely different time as far as AIDS, AIDS treatment and therapeutics were concerned. Did you practice for a time?

Mark Dybul: I practiced at NIH so

I was clinical at NIH. It’s a unique environment. There’s an astounding clinical center. It’s a real jewel and

in the American Health System. But basically all the work you do is tied to basic and clinical research. So I—we all in my

group anyway, while we did clinical work, during my fellowship to be certified in infectious diseases and went to various hospitals

around the Bethesda, Maryland area in Washington, DC and Baltimore. And then also was had a clinic, an HIV clinic at NIH. But then

did clinical research based out of that and then expanded that clinical research to Africa. So I was an active clinician, with

a license up until I became the deputy US Global AIDS Coordinator running PEPFAR at which point it became too difficult to manage

running of a growing, you know, by billion dollars a year, program and maintain a clinic.

Matt Pillar: Yeah, you characterize

it interestingly when you say you were a civil servant, effectively developing or leading a startup within the US government. I

mean, that’s an opportunity, an amazing opportunity on one hand. On the other hand, you know, getting into politics and government

is, you know, there are plenty of folks who would say, “you know what, I think I’m going to apply my talents and expertise,

a different way.” Tell me about your mindset at the time, like what inspired you to—obviously the prestige right—but

what else inspired you to embrace that role as a civil servant, working within in the US government?

Mark Dybul: I actually never thought

about the prestige of it at all. In fact, it was the opposite. It was more humility of being able to become involved in the largest

international health initiative in history for a single disease. And the humility of the people involved in the US government,

in Washington, and in particular, in the countries visiting villages where people were literally giving everything of themselves

for their neighbors was a very humbling experience. I think what drives people to do that, and I hope, you know, in this world

today, people don’t think highly of government all the time, but the opportunity to do huge things you can’t do outside

of government, and to do an international initiative across the Department of Defense, the Department of Health and Human Services,

the State Department, the three biggest, some of the three biggest departments, what’s called USAID, our development agency,

the Department of Labor, the Peace Corps to bring all of that together to support what was thought to be impossible by the public

health community. The scale up of antiretroviral therapy in Africa, where literally the vast majority of public health community

said it was impossible. The systems couldn’t be built. There weren’t enough health care workers there were and they

were right. There weren’t enough health care workers, there were no logistics systems, there were no supply chains. No one

had ever tried chronic delivery systems in Africa at all. There was no roadmap. There was just a vision and a trust that it can

and needed to be done. And so the opportunity to be involved with that was what motivated all of us. But it was a startup. I mean,

when we began, people just thought about how much money are you spending? The answer to any—what are you doing in education,

health? The answer would be we’re spending X amount of money, not we’re achieving this. It was very clear in directive

from President Bush, don’t ever come back to me telling me how much money you need. Tell me what you’re going to do

and how you’re going to do it. And I’ll find the money. So it was a bottom up results based approach. Bottom up budgeting,

very common in business, bottom up management, and top down management, with command and control with very specific results that

we managed against and got results reported every six months and managed against those results moving money, moving managers basically

bringing business across the US government and a startup mindset. And there’s nothing harder when people say, “Oh,

it’s so difficult to run a public company.” I’m like “try running a startup in the US government, across

multiple agencies.” You basically have a board of 700 people, the entire Congress, the entire executive branch, the Department

of State, and all the agencies. So it’s like having multiple divisions, but secretary level, four-star-general level as your

division heads, trying to push, and then dealing with all the countries and the systems and each country is different. So you can’t

do a more difficult startup. And it was very exciting. And I learned a great deal about management. I learned a great deal about

results-based orientation. I really learned a great deal about setting targets and meeting them. So we met in the US government

on target, on budget, the results, which has now saved 25 million lives.

Matt Pillar: Yeah. And similarly to

running a startup going into that appointment. I mean, you had to know that your time there would more than likely be finite, which

is often the case and startup environments, right. Like I’ve interviewed a lot of biopharma executives on this show, and

very few of them have, you know, 20 plus years, 10 years with the same company.

Mark Dybul: Nor should you.

Matt Pillar: Sure, right, yeah, you

take opportunities to have more different, better impact.

Mark Dybul: And train the next generation.

You should be putting yourself out of job, train the next generation to takeover, to think creatively, differently, to have vision.

No one person’s ever going to be responsible. It’s always a team effort and you have to bring that next generation.

Matt Pillar: What were your thoughts?

You know, first of all, I’m curious how that wound down, I’m assuming it wound down as a result of sort of—your

appointment specifically wound down as an administration change, a political thing?

Mark Dybul: I was actually asked to

stay on by the Obama administration for a period as you know, as a functional civil servant, and then when that ended, I went back

to NIH with Tony, stayed there for a couple more months and then decided to go over to Georgetown University and leave the government

very happily, after having had the opportunity to serve.

Matt Pillar: What remains of what

you, again, fully recognizing that the AIDS therapeutic landscape has advanced considerably, thanks in large part to a lot of the

work that you did. So I’m sure it’s a different effort now, a different organization. What sort of remains of the legacy

that you began to build there?

Mark Dybul: Actually still very much

running now in 20 years with a total expenditure of $110B and 25 million lives saved. We reach 2 million at the time of five years.

It’s a hockey stick, you know, you get started and you build the systems and that was the key. You build the system so that

you can continue to enroll. And we did these very careful calculations, not that common in government, how much would it cost per

person for the first six months and then for the next, for the rest of their lives? So it’s very economic driven. So that

program is still existing, a lot of the foundations that we laid are still very much in place and has continued to grow and expand

and build systems. Health systems that are now the foundation of health systems across Africa, and actually allowed them to respond

to things like COVID, Ebola and other diseases. So the legacy continues in a very fundamental way.

Matt Pillar: Very good. And when you

when you made the decision to go back to Georgetown, so you went back to the NIH for a bit and then went to Georgetown. That was

to pursue, continue your career in academia?

Mark Dybul: NIH is functionally an

academic setting. It’s one of the best universities in the sense, in health in the world, if not the best. And I gone through

my government years in academia except for the time at the AIDS program, and I thought it was time to step back after 14 years

in government and move to a university base. I went to Georgetown for all my schooling, undergrad and medical school and wanted

to have that base, rather than going back to NIH and build something new. So we started to develop new programs around policy and

an impact in Africa primarily around HIV and other infectious diseases. And we’re funded by the Gates Foundation, Hilton

Foundation, other foundations to do important work, ultimately. And now as a professor at Georgetown, while I’m CEO, which

as you know, is not that uncommon, the programs I started and continue became grantees of the President’s Emergency Plan

for AIDS Relief and the Global Fund, the organizations I used to run, so now I’m basically on the other side of those.

Matt Pillar: What were you teaching

at Georgetown and what do you continue to teach?

Mark Dybul: I guess I teach in general,

public health, public health policy, HIV and leadership and management.

Matt Pillar: Very interesting. So

the trend as you mentioned, not uncommon at all to have, we’ve had plenty of them on the show, academics who are also CEOs

of biopharma companies. What was the, I guess, first inkling of motivation to join industry in your mind, like what was appealing

there?

Mark Dybul: I’ve done a lot

of other things. But I think what grabbed me is the same thing that grabbed me for PEPFAR, an opportunity. So business can move

in different ways and I was fortunate to be introduced to some truly innovative technology that could potentially radically change

the landscape, first for HIV and other infectious diseases. And then secondly, cancer. And, really, my mission has shifted and

the vision of Renovaro has shifted to and I believe this is possible, freeing us from toxic chemotherapy in our lifetime and to

provide people with healthy—living with cancer—with healthy longevity without toxic chemotherapy. And immunology is

the basis of that and my entire career has been built on immunology and how the immune system functions and if we can retrain the

immune system to recognize tumors in a different way, not the way the current immune system is because obviously, that’s

failing. But if we can retrain it using effectively tricking the immune system, using the immune system and what we know about

it, and building products, cell, gene and immunotherapy products around that, we can shift the way the immune system works, so

that it can control the tumors. To retrain the immune system so that it can control the cancer without the need for toxic chemotherapy

that destroys not only cancer cells, but all the rest of our—many of our other cells. And that’s the vision that I

think is fully achievable. And it’s achievable by understanding the immune system and building products like the one we have,

but also by including advanced technology, like AI. Really, a lot of people talk about AI. Everything’s AI now. Really what

it is, is deep learning and deep algorithms, based on massive datasets that are trained to identify things in the same way we’re

retraining the immune system. You’re using data, massive datasets, and using technology to train algorithms to find things

that would be impossible for the human mind, or simple experiments to identify. And when you put those two powerful things together,

I believe we can achieve extraordinary things in health, longevity, and better lives. And that’s what excites me now.

Matt Pillar: I’ve got some questions

for you on that here in a minute around your recent merger acquisition.

Mark Dybul: It’s in process.

It’s a combination. So we’re waiting on the proxy vote. So the definitive agreement has been signed, and we’re

waiting the proxy vote which we believe will occur, our hope intend to have occur early next year.

Matt Pillar: Well, we’ll dig

into that, that technology here in a minute. But before we get too far away from sort of that transitionary period, you know, one

of the interesting, I think juxtapositions in my mind is what you described earlier as a startup within the federal government

where, you know,

the Bush administration was basically saying, we want to do big things. Don’t tell me how much you’re

spending. Tell me what you need. When you found a startup, biopharma company, you don’t get to go to the President of the

United States and Congress and say, “Hey, where’s that blank check?” You know, “here’s what we need

to stroke on that blank check.” So tell me a little bit about that learning experience for you. I often interview execs who

came from big bio before they founded a company and they tell me about boy, you know, “it was one thing being in a super

well-resourced organization. It’s quite another when you’re scrapping for money, and you’re answering to a board

and accounting for every time.” So tell me a little bit about how you reconcile that.

Mark Dybul: It gets a little bit to

doing a startup in the US government is far more complicated than anything in the public sector, and certainly, including raising

money. So there’s a misconception that a president just decides to spend X amount of money and that’s all and then

you’re done. You just go do it. Not how it works. There’s an annual appropriations cycle. There’s a congress

which is functionally a board of 535 people and you have to defend why your program and why money for your program, and this is

development money going to Africa, is more important than all the other priorities that the US government has. And to go from,

to increase budgets in the US government is virtually impossible. To increase them by a billion, a billion and a half a year for

a development program in Africa, is unheard of, and has never happened before and is probably never going to happen again. But

we had to every, literally every year fight for every penny. And that included within the administration because the administration

is not the president. There’s the Office of Management and Budget. There’s the National Security Council and they’re

all fighting for those resources. So you have to prove that what you’re doing is impactful enough every year and you have

to explain to them what’s working, what’s not working. Why this vision is better than every other vision sitting in

front of them. I’ll never forget being the Office of Management and Budget, and we were asking for an increase of $450 million,

which at the time was 50% of our budget. And the President’s brother was governor of Florida had just walked out as we were

walking in. He was like, you know, he just asked me for a lot less. Why should I be giving it to you and not the President’s

brother who is the governor of Florida? So you have to in ways that do not exist in the in the private sector, you have to explain

every last penny and you have to convince the entire White House, your bosses at the State Department in my case and the entire

US Congress every year to do that. There is nothing more difficult in terms of fundraising. And then on the global stage when I

ran the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria, we did three year cycles. When I took that program over, it was collapsing.

Germany, Switzerland and several other large donors had withdrawn because of basically some difficulties in management. And it

turns out there were a lot of issues with management. Not the managers, (they) were great human beings, but they were running a

massive organization at the time $3 billion which was half of what I used to run, $3 billion a year, but it was being run like

a small NGO. So all the business systems had to be built and put in place and I led that effort, but I was raising money from every

country in the world, every major country in the world. So I had to go to every Parliament every head of state every three years.

Bill Gates was involved, you know, he massively increased his contributions while I was there, and he helped us fundraise but you

had to go every and you have to keep those three year cycles, you had to go all the time and explain why your program and all the

things governments had to fund was important enough to go from three to four and a half billion dollars and to restore confidence

in four years. So it’s a it is a very complex thing, to do those things that to be honest, in terms of fundraising in the

private sector, is much, much, much easier and much less complicated.

Matt Pillar: Even though during many

of those years you had Bono at your side. I mean, you had Bono.

Mark Dybul: Bono is a great, great

help. But—and politicians love having pictures—but Bono’s unique in that he can explain why things should be

done. Bill Gates has that star power but can also explain why things should be done. They were great allies. And you have to do

this in business. You know, no business operates alone either. When we have our oncology products, and when we have our AI products,

you have to convince doctors and hospital systems,

why they should be buying your product and not someone else’s. And that

same effort and that requires partnerships, that requires getting people who the oncologists listen to, who the hospital has to

listen to, who the insurers listen to, so that there’s enough of a system. Even in the regulatory process, you want advocates

out there pushing for what you’re doing, knowing how to build those partnerships. That’s how business succeeds rapidly.

A lot of people think you end when you have a product, you start when you have a product and you start long before you have that

product to prepare the pathway so that when the products available, you’re ready to roll and you’re ready to move into

a market in an aggressive and commercial way. That’s very similar to the types of partnerships and things we had to build

for both of the programs I was privileged to build and run.

Matt Pillar: That element of biopharmaceutical

leadership, that passion and advocacy, was that in you prior to your global stage and federal leadership experience, or is that

something you learned as you—

Mark Dybul: I learned that coming

along because I was an academic. I mean, I ran a lab, very successful lab with lots of academic publications. I get flown all over

the world to speak on the science and that was a very different life. When I started running or taking over these programs we were

buying, we were the largest procurer. We bought billions of dollars a year in pharmaceutical products, in band aids and in everything

that you need for health. 1000s of bodies literally and had to negotiate with CEOs of every major pharmaceutical companies. We

also did public private partnerships with huge companies, including Coca Cola, for example on supply chain. Who’s better

at understanding supply chain than Coca Cola? So not only in the pharmaceutical sector where we were big procurers and negotiated

but also to partnerships to deliver health care, same with huge corporations, like Coca Cola. So it was very much a learning experience,

but one that was very exciting to engage at that level and understand how companies work which is not too different. In the end,

everything is run by humans. If you understand human beings, you can understand any part of that in the private or public sector.

Matt Pillar: Everything is run by

human beings right now. We’ll talk a little bit about AI here in a minute. We’ll test that theory. So Renovaro, before

we get into the technology and some of the moves you’ve been making, the company has not been without its own challenges

that sort of tested its mettle. Prior iterations of the company have forced you as its leader to power through some unbelievable

drama, you can read about it and I’m not gonna get into the details right now. But you know, people familiar the company

know, there’s been some considerable drama in terms of the leadership iterations of the company. So I’m curious about

that element. I mean, obviously I and our listeners, we’re sensing your passion, your advocacy, your drive. But when it comes

to leadership from an organizational standpoint, especially when there’s, as I said, considerable drama happening, what’s

key to Mark Dybul, maintaining and at times correcting the course of a company that you’re trying to build.

Mark Dybul: I think, you know, some

of the things that I learned running massive organizations with enormous political and public challenges as I mentioned, the Global

Fund when I took over donors were running away from because of some internal management problems, and inspector general reports

that found money missing. Imagine what it was like in Washington, DC, pushing for programs as Democrats, Republicans, everyone’s

moving around, and the presidency changing over the years. These are very complex things and we were on the front page of newspapers

regularly with challenging things. In crises, the most important thing is to stay focused on what your mission is, to remain humble

and learn. As my former boss used to say, when you’re in a hole, stop digging, which many people have a tendency to do, and

be very transparent. And this is something I learned in all the programs I’ve ever run. And that’s true here, be honest

about what your problems are and what you’re trying to do, what your solutions are, and be transparent about that. And that’s

precisely what we’ve done and if you maintain those principles, you can manage through anything. But if you see where you’re

going and what your mission is, you can manage anything and that’s what we’ve always done. We’ve seen the opportunity

and the potential to revolutionize health care for people and the opportunity to manage and remain humble and learn and adapt and

be transparent. And be transparent with the public, be transparent with the board, be transparent with investors. And if you do

those things, you can manage through just about anything. And I think we’ve done an awfully good job of doing that as a team.

Our board is extremely strong. You know, the former interim CEO of Gilead pharmaceuticals are scientists, one of the largest pharmaceutical

companies in the world, who was general counsel before is our lead independent member. We have other very impressive board members,

our board chair, started Pandora jewelry, so we have very strong board that stuck with it. And the scientists who have been engaged

have stuck with us from the beginning and continued in power through and continued to show tremendous results. So stay focused

on your outcomes, your results, your mission, be humble, learn and be transparent and that we’ve done.

Matt Pillar: Yeah, that’s fantastic

advice. And I’m going to ask you one more question on that, for the benefit of new maybe first time, biopharma CEOs who face

a crisis or a challenge. You know, it’s one thing to have that mindset to embrace you know, stop digging, start climbing,

surround yourself with the right people, you know, move forward, stay true to the vision, you know, these are like, built in, in

a way I’m sure like built into your DNA,

you learn that behavior, you get good at it. But there are moments you know, in

anyone’s mind, no matter how well accomplished you are, no matter how confident you are, there are moments where you go home,

and you say, you know, “I could do a lot of things. Because I’m accomplished because I’m confident I can do a

lot of things. Things are going so poorly right now with this thing that I’m trying to do. Maybe I should go do something

else.” In that moment, you know, when the fundamentals that you just mentioned are sort of sure, you know, built in but they

don’t seem to be doing me any good like in this moment, give me some advice or give some advice to the executive who’s

like in that moment going I don’t know if I should fold.

Mark Dybul: Look, look into who you

are and what you are. I mean, if you get to that level, presumably you’ve thought a lot and stay true to who you are. So

I grew up in the Midwest, with very, very basic fundamentals that you don’t quit. You look for opportunity and you fix things

wherever you can if the mission is right. And if the mission is right, that everyone has doubt, if you don’t have that doubt,

and that humility to learn, then you’re going to be catastrophic, because you’ll make bad calls and we all make mistakes.

We all make decisions at times we wish we had not made but if you focus on your mission and stay strong and just never give up.

As long as the mission is right, never give up. As long as the vision is right, never give up. Find a way. You can always find

a way if you remain calm, balanced, willing to learn and remain transparent. So, not everyone can do that to be honest, and not

everyone can. And you learn pretty quickly whether you can or not when you’re in leadership jobs like that. And I learned

that—and there were times the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief when I was being heavily criticized by former

friends in public, splashed across front page news articles that my family would see for political purposes. I would think about

my lovely life back in NIH, being a scientist in Tony Fauci’s lab and flying all over the world giving lectures with none

of that ever possible. But the possibility of contributing to saving millions of lives. Yeah, you can’t do that. That’s

not who my parents built. So, but it’s different for everyone and everyone needs to find their own energy. For me, it’s,

you know, what is the mission? And I will never give up.

Matt Pillar: I like the props to Mom

and Pop Dybul. That’s very nice. Alright, so that’s a beautiful segue to the mission at Renovaro. And when I look at

your pipeline, the first thing that strikes me before I dig in some of the cool stuff that you guys have been doing. The first

thing that strikes me is its depth and its breadth, right? Like you HIV, HBV, infectious disease, oncology. What’s the overarching

strategy? What’s your portfolio strategy there?

Mark Dybul: Yeah, the overarching

strategy. I guess you could look at that and say, wait, that’s too much for a startup. But it’s all built around platforms

and platforms mean a lot I think to me personally, but I think scientifically and also as a company. Because platforms mean you

are investing in something that can attack multiple different approaches, which gives you multiple markets and saves multiple people’s

lives, improves lives in multiple areas, but also gives you multiple markets and multiple commercial opportunities. And so those

platforms are hugely important. So we have platforms that then can be basically spun into different diseases. Right now by far,

lead candidate is in oncology. The data there are super impressive to me scientifically. The woman who conducts those studies,

Dr. Anahid Jewett at UCLA who has been conducting most of the studies and designed the model to study pancreatic cancer described

as the holy grail of cancer research. So what we’ve seen and we started—and I’ll get into why we started with

pancreatic cancer, but it’s a platform which should be as powerful against any solid tumor. Pancreatic is particularly difficult

tumor to combat and 80% of all cancers are solid tumors and some extremely difficult to treat. So the reason she described as a

holy grail is we see four things consistently across five different humanized animal studies. Now human is important because it’s

basically replicates the human immune system, rather than guessing if a mouse system is going to translate to human. In five independent

studies that she’s conducted, we’ve seen the same thing, 80 to 90% reduction in size of the tumor, which in and of

itself is pretty impressive. But secondarily, when you look inside, what’s left in the tumor stack, what’s there if

it’s all tumor, that 10 to 20%, all tumor, that’s not as good an outcome and it’s probably going to come back.

When what we see though is what’s inside the tumor sack is effector immune cells that are still there, meaning they would

still correlate with ongoing killing the cancer and this is after only one cycle. In humans would probably be five to 10. The third

piece of that is in the periphery. In the blood, we see immune-stimulation both at the cell level but also what’s floating

in the blood, really important things like gamma interferon, that would correlate with the ability to kill cancer, and we find

it in the blood and the reason that’s important is the fourth thing we see is no metastases. Whereas if you in controls,

you know either with our product, but not with all the things we do like the gene therapy, it’s a dendritic cell, allogeneic

dendritic cell, if you use those without the gene therapy, or if you don’t load them properly with the tumor, what’s

called mock or fake control, there’s metastases, the tumor doesn’t decrease and you don’t find those same immune

correlates in the blood. And that is very powerful. And pancreatic cancer, as I mentioned, is very difficult to treat. We’ve

intentionally focused on cancers difficult to treat like pancreatic. And then our clinical trial that we proposed to the FDA and

we’ve had our pre-IND meeting and formal IND. There was no comment at all actually on the clinical trial design. We will

include not only pancreatic cancer, but other cancers that are difficult to treat. We haven’t selected for sure. But for

example, triple negative breast cancer, which is extremely difficult treat. Liver cancer, secondary therapy is terrible. Head,

neck cancers, there are some cancers that are extremely difficult to treat, but they’re still very common. 60,000 people

in the US alone are diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and at five years only 5% to 10% of them are alive. And if you don’t

get diagnosed really early, only 2 to 3% are alive. Same with triple negative breast and these other cancers. So we will help a

lot of people we believe if the data is seen on the mice are replicated in humans, and improve their lives without toxic chemotherapy.

But also you can move very quickly through the regulatory processes because there’s no available therapy. So for example,

in the recent weeks, the FDA rapidly approved CAR-T therapy for a certain type of cancer with really not large sample sizes because

there’s no option. CRISPR was approved for sickle cell disease with a not a large patient population because there’s

no good option. And so when you focus on cancers, particularly in the part of the Food and Drug Administration that reviews biological

approaches, cell gene immunotherapy, you can move very quickly. And so we anticipate starting clinical trials towards the end of

this coming year, and having enough results by the end of 2025. That again, if the results are replicated, we could actually receive

approval by the end of 2025, early 26 with indications for several very difficult-to-treat cancers. And this is of course would

need to be proven. But if you can use a product and the immune product to treat difficult-to-treat cancers, you should be able

to treat relatively easy-to-treat cancers, which means you would move into studying in first line therapy. So for example, if it

works in triple negative breast, surely it will work in regular breast, which is a huge population of women who suffer and often

need chemotherapy and radiation therapy and radical surgeries. If you can switch immune therapy for something like that. But imagine

what that does and that’s why we have this hope, this vision for a future free of toxic chemotherapy. Now we’re a business

too, and that’s one of the beauties of how we’ve structured ourselves. When you have those types of things off of a

platform, you can sell, you can partner, you can build, you can license. There are so many business opportunities that come with

that human advantage, that human improvement, that great improvement to people’s and family’s lives that we’re

so committed to. But there’s a real business side to this, too, and how we proceed it. And we’re doing that similarly

with the combination that we hope will be successful in proxy with the AI company GEDiCube to promote even more advanced ways to

diagnose cancer early, to identify recurrence. And the earlier you identify, diagnostically or recurrence, the better, more effective

your therapy is going to be. And then also to predict success and failure with therapy, which we believe AI will give us the capacity

to do, those deep algorithms. So you combine what I described as bottom up science,

what is the biotech side where we begin with

hypotheses, knowledge of the immune system, knowledge of cancers, how you could overcome those with cell, gene and immunotherapy

with almost a top down agnostic, massive data set trained algorithms. So we’re training data to be used better using algorithms

and artificial intelligence and we’re retraining the immune system to respond better where those meet. That is a big bang.

I mean, that is a tremendous opportunity to rapidly move not only in cancer, but eventually in other diseases that we’re

very hopeful will radically change the future, and, in a sense, redefine the future of medicine. Imagine going and being able and

we’re not there yet but a man being able to go to a doctor in where a blood test in 72 hours or in the future while you’re

waiting, can pick up very early stage cancer or the likelihood that you will develop cancer, and with that same analysis say this

is the best therapy for that, this is unlikely to work. Imagine how that would change not only a person’s life and longevity,

but just the comfort level that the scariest time is when you don’t know what you have. You don’t know what you’re

going to be treated with. If we can undo all that, if we can redo all that then the future of medicine is radically different.

And the future of therapy is radically different. And that’s the future we see. We’re not there yet. But that’s

where the power of bringing biotech and deep algorithms is so important. To be honest, I don’t think if—you’ll

see every day, a report of a big pharmaceutical company or big biotech buying up or partnering with an AI company. Those are very

different cultures. We talked about—there’s biotechnology and there’s technology, very different backgrounds,

very different mindsets, very different approaches. And we see those in our own people, you know, it takes good management to have

people understand why they come together. But that culture clash is going to be extremely difficult in large companies and large

bureaucracies. And if you don’t have that management history of how do you bring disparate groups together? How do you bring

people who are fundamentally looking at things differently together? Fortunately, I and other managers we have, have that background

and we’re also small enough that we can capitalize on all of this. And we built the companies so that we can functionally

spin out almost an endless number of subsidiaries whether they’re AI clones or new technologies. And so the future, both

for us and for others, I think is extremely fascinating and a whole new world. It’s one of those times in history where technology

matched with our current knowledge could lead to a radical jump, a radical leap forward, that will improve the lives of many people

and have healthy longevity. Not just longer lives, but healthier, happier, more fulfilled lives.

Matt Pillar: Yeah, it’s interesting,

looking at the landscape of companies, biopharmaceutical companies that are leveraging deep learning, machine learning, AI tools,

computational biology tools, for lack of a better umbrella term. I’ve had plenty of conversations with super young Silicon

Valley bred biopharma companies that didn’t start as biopharma companies. They started as tech companies. They had the tech

tools before they decided to develop a portfolio or a candidate, and then plenty who are selling applications to biopharma companies.

I don’t want to age you, Dr. Dybul but, you know, for a guy who’s adopting computational and deep learning, you’re

probably on the upper scale, right, like, age-wise. When did you fully embrace that, and two, do you think it matters? Like do

you think it matters whether a company is like, has that kind of dyed in the wool tech application background going into biopharma

or a more traditional biopharma company that grew up in the wet lab and traditional research is now adopting applications to help

create efficiencies around discovery and development?

Mark Dybul: I think it’s a great

question and there’s no right answer to that. I think the challenge is adapting and learning totally different ways of approaching

and thinking about something and that’s extremely difficult. And that’s why a lot of mergers have failed historically,

because you’re bringing different cultures, different mindsets. And so you really have to have a group that can adapt. So

the tech company that we’re in the process of joining with, GEDiCube, is a technology that started with FinTech, actually,

and was adapted to health tech now. It’s 10 years old. It’s an award winning technology that uses a multi omic approach,

not a single approach. Not just genes, but proteins and how proteins fold all in these stacks. Extraordinary stacks have been developed

over a decade, with deep, deep, deep learning. With so many different data points and through a partnership with Nvidia, and their

inception program, they are adding imagery to that. Imagery is a very potent addition and working on pathology additions. The CEO

of that company comes from Nvidia and so the technology piece is hugely important, but I’m not just unfamiliar with tech.

I mean, I grew up at NIH where tech was, you know, at the forefront of everything and I also was very involved in AI tech related

to biosecurity. I have led commissions and put up such recommendations.

Matt Pillar: I didn’t mean to

disparage your tech chops. Just comment—it was an ageist comment that—

Mark Dybul: Old people can learn,

too. But the reason I want to make that point is and this is important about how we’ve structured ourselves. If the

proxy goes through, GEDiCube will remain a subsidiary and so they can advance their technology the way technologists would because

you don’t want a big company coming in and telling people who know what they’re doing in tech, “don’t do

it that way, do it this way.” You want them to be able to move same on the biotech side. We don’t want tech people

saying “oh you need to change that” and do top down driven agnostic approaches. No, we have a pretty good idea how

the immune system works, and we’re seeing great results. So both will move independently towards their commercial product.

But then the opportunities to bring them together to develop joint approaches that will leverage and have a multiplier effect in

both and that’s where the skills come in. And the ability to listen to each other and learn from each other without squashing

the uniqueness of the approaches that people are taking, let those flow but also let them come together and find new opportunities

that will create as I said, almost an endless number of subsidiary opportunities both on the health tech side, on the biotech side

and then the two together, which is the extraordinary piece to me. I think that’s where the future lies.

Matt Pillar: There are so many levels

of opportunities, applications for AI in biotech, it’s impossible to cover them all, you know in one conversation, but it’s

a sexy term right now, right? Like even folks who are just kind of doing a little bit of dabbling, you know, are leveraging that

term. A friend of mine, a guest on the show Andrew Satz put it best I’ve quoted him before but he said “AI and biopharma

is like sex in high school.” He said the kids who say they’re doing it aren’t, really aren’t, and the kids

who really are, aren’t talking about it, right? What do you think about how all in should an emerging biopharma be right

now? Is it something that you know, there are applications where you would advise like testing the water? Or is it your mindset

like that if you’re not doing this, if you’re not applying these tools you put yourself at great peril?

Mark Dybul: It’s a great question.

I love that. I love that quote, actually. Another friend of mine said we need to take the BS out of AI. Because everyone’s

saying I have AI this, I have AI that, and they don’t. That’s why when we wanted to engage in deep learning and technology

we identified a group that has a 10-year track record of developing things, and the fact that you start in FinTech and moved to

health tech means a lot to me. I call it Venn tech. The Venn diagram where these two worlds come together and then how do you exploit

those maximally? And it doesn’t mean you can’t succeed either doing health tech alone, or biotech alone. You can but

if you’re really trying to shape the future of medicine, if you’re really looking for what will we be doing in 10 years,

I don’t see how you do it without the two. At the same time, if you don’t do the tech well, and if you don’t

do it right, and you don’t have that 10 years of people who and—building the algorithms, you just have something on

a whiteboard, and you have to be very careful about that because similar and I think about this a lot with gene therapy, think

about where 20 years ago we thought gene therapy was going to solve everything. Tech is not going to solve that—health tech

is not going to solve everything. The key is finding that Venn diagram that then help, where do the two actually come together

and create a multiplier effect. And it’s not everywhere. And which is why I think we’ll see a lot of failures, a lot

of people saying, talking about what they’re doing in these two worlds and bringing them together who don’t have very

deep tech, or cannot because of the culture and mindset clashes put the two together and don’t have the vision for where

the two intersect. And if you try to force things together that don’t belong together that’s going to fail. So that’s

where’s the Venn tech, where do the two naturally cross which is why we’ve structured ourselves so that the two are

in a sense, independent, advancing health tech, advancing biotech, but then bringing them together where that Venn tech exists.

Matt Pillar: Perfect. The Venn diagram

and I know this is the question that’s going to make your IR people a little bit nervous because I am going to ask you to

make, at least wax a little bit on a prophetic vision. So right now, most of the discussions I have with biopharma companies that

are truly engaged in AI, the conversation is around discovery and molecular design, seems like the low hanging fruit applications

at least generally speaking. Where do you see AI, where’s there in your mind the most promise for that technology, beyond

discovery and design, perhaps the clinic, perhaps manufacturing, perhaps even you know, real world evidence, well after commercialization?

Where are the opportunities that you’re forming up in your mind beyond the early stages?

Mark Dybul: I think real world evidence

is definitely important. It’s not something we’re going to focus on at the beginning. So let me tell you about where

we see the opportunity, which gets here some of the comments that you made. You know, finding potential new drug products is definitely

important, but that to me is the least low hanging fruit. It’s a great way to identify a bunch of new products,

but you then

have to study all those products. And I think if you back up a little bit and this is what we think is real potential for rapid

change is liquid biopsy, basically blood, liquid biopsy rather than getting tissue all the time and using algorithms to identify

predictors of disease or actual disease much earlier. Find those markers and we think that’s very possible in a very short

period of time. And then identify by following people who have been treated with various things, the ability to predict if a product

will in fact have its impact on the person. So for example, PD-1 inhibitors, biggest thing in cancer therapy right now, generally

a 60% failure rate. What could you predict who’s succeeding and who’s failing? At $50,000 as therapy or somewhere in

that range? Be pretty good to know if someone’s going to likely to succeed or fail with that therapy or any other therapy

for that matter. And using deep learning algorithms with the data in them, I believe we should be able to find those markers that

predict whether or not a therapy is going to work. And the money is an important piece but think about the patient who’s

waiting for six months or 12 months for their images to pick up the fact that their cancer has been growing because the product

is not working. So that person has basically lost their battle against cancer because we couldn’t predict whether or not

the therapy was going to succeed. So early diagnosis, prediction of likelihood of success to therapy, and then picking up recurrence

early so that you can, and again, predict which therapy is best. You combine that with biotech or the ability to study rapidly

and in that finding of what therapy is likely to work not to work, you’ll start picking up signals of what could work in

the people who are failing. The other area that is hyper exciting to me is right now we’re mostly an off the shelf allogeneic

dendritic cell that’s loaded, that’s genetically modified and loaded with piece of the person’s tumor. So it’s

very personalized therapy. If you have enough of a data set you might be able to find common antigens, proteins, across multiple

tumors, either within the same class, say pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, breast cancer or across multiple tumors that would

then create next-version products that could be even more effective. So I think the early identification, predictability, that

to me is a low hanging fruit. And the data are telling us it’s possible, especially if you don’t just use genes but

if you use a fully multi-omic approach which GEDiCube has which looks at genes, proteins, trans genes, how proteins fold already

in the stacks, but then add on to that other modes like imagery, pathology, then you have such deep learning across so many things

that you can start filtering out the noise and really focus. So you know, I totally get the “let’s look for the new

drug target product” and I think that’s a great business that people are working on. I think the business we’re

focused on could have that Venn effect, that Venn tech effect in a really hyper exciting way.

Matt Pillar: Very cool and we’ll

check with the IR folks later on to make sure that answer was acceptable, Dr. Dybul. I’m abusing your time. So I’m

going to wrap things up here but I want to give you an opportunity. And listen, I could talk to you for the rest of the afternoon.

I can keep asking you questions as long as you’ll sit there, but I won’t do that to you. We’ll do a part two

if necessary. But I want to give you an opportunity to wrap up with some big next steps for Renovaro. What are you most excited

about what’s happening like imminently at the company?

Mark Dybul: I’m hyper excited

about the potential for this combination with GEDiCube, which of course the shareholders have to decide, which we believe will

lead to actual commercial products around diagnosis to begin, early diagnosis to begin and then predicting therapy, therapeutic

response and recurrence in this coming year, in 2024. And then, as I mentioned, and by the end of 2024, we believe that you know

the will have submitted our IND and begun our clinical trials. We’re already preparing everything that needs to be done to

start that trial as soon as the IND comes in for starting with pancreatic cancer and then other cancers that are difficult to treat.

And if the humans look like anything like the mice, that means we could actually have products to people to change their lives

by the end of 25 and 2026 in the market widely available. And then combining those two together, I can’t tell you how excited

I am, what the future of medicine will look like. And it reminds me of the early days of PEPFAR, when everyone said it’s

impossible to do antiretroviral therapy in Africa, it’s too complicated. There are no systems all of this does doesn’t

exist. There are 1000 reasons why something won’t work. What we see are that handful of reasons why it will work. And that

excites me because we have the right team. We have the right board. We have the right management. We have great scientists to put

that all together and to truly be a significant player and are poised to do so to help redefine the future of medicine.

Matt Pillar: Fantastic. I appreciate

the opportunity to meet you and talk with you and I’m excited as well. I’m excited about following the company. We’ll

be paying attention and as I noted, I hope to have you back on the show at some point.

Mark Dybul: Thanks a lot, Matt. Really

enjoyed the opportunity to catch up with you.

Matt Pillar: Thank you Dr. Dybul.

That’s Renovaro Biosciences, Dr. Mark Dybul. I’m Matt Pillar and this is The Business of Biotech. We’re produced

by Life Science Connect with support from Cytiva, which puts its support of new and emerging biotechs like Renovaro on full display

at its emerging biotech accelerator, which you can visit it’s cytiva.com/emergingbiotech. We also offer a trove of supportive

content for emerging biopharmas at bioprocessonline.com, where you can find the complete library of The Business of Biotech. And

subscribe to our monthly newsletter at bioprocessonline.com/BLB. Check it out and in the meantime, thanks for listening.

Forward-Looking Statements

This transcript contains “forward-looking

statements” within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities

Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. All statements, other than statements of historical fact, included in this communication that

address activities, events, or developments that Renovaro or GEDi Cube expects, believes or anticipates will or may occur in the

future are forward-looking statements. Words such as “estimate,” “project,” “predict,” “believe,”

“expect,” “anticipate,” “potential,” “create,” “intend,” “could,”

“would,” “may,” “plan,” “will,” “guidance,” “look,” “goal,”

“future,” “build,” “focus,” “continue,” “strive,” “allow”

or the negative of such terms or other variations thereof and words and terms of similar substance used in connection with any

discussion of future plans, actions, or events identify forward-looking statements. However, the absence of these words does not

mean that the statements are not forward-looking. These forward-looking statements include but are not limited to, statements regarding

the proposed Transaction, the expected closing of the proposed Transaction and the timing thereof, and as adjusted descriptions

of the post-transaction company and its operations, strategies and plans, integration, debt levels and leverage ratio, capital

expenditures, cash flows and anticipated uses thereof, synergies, opportunities, and anticipated future performance. Information

adjusted for the proposed Transaction should not be considered a forecast of future results. There are a number of risks and uncertainties

that could cause actual results to differ materially from the forward-looking statements included in this communication. These

include the risk that cost savings, synergies and growth from the proposed Transaction may not be fully realized or may take longer

to realize than expected; the possibility that shareholders of Renovaro may not approve the issuance of new shares of Renovaro

common stock in the proposed Transaction; the risk that a condition to closing of the proposed Transaction may not be satisfied,

that either party may terminate the Transaction Agreement or that the closing of the proposed Transaction might be delayed or not

occur at all; potential adverse reactions or changes to business or employee relationships, including those resulting from the

announcement or completion of the proposed Transaction; the occurrence of any other event, change or other circumstances that could

give rise to the termination of the stock purchase agreement relating to the proposed Transaction; the risk that changes in Renovaro’s

capital structure and governance could have adverse effects on the market value of its securities and its ability to access the

capital markets; the ability of Renovaro to retain its Nasdaq listing; the ability of GEDi Cube to retain customers and retain

and hire key personnel and maintain relationships with their suppliers and customers and on GEDi Cube’s operating results

and business generally; the risk the proposed Transaction could distract management from ongoing business operations or cause Renovaro

and/or GEDi Cube to incur substantial costs; the risk that GEDi Cube may be unable to reduce expenses; the impact of the COVID-19

pandemic, any related economic downturn; the risk of changes in regulations effecting the healthcare industry; and other important

factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those projected. All such factors are difficult to predict and

are beyond Renovaro’s or GEDi Cube’s control, including those detailed in Renovaro’s Annual Reports on Form 10-K,

Quarterly Reports on Form 10-Q and Current Reports on Form 8-K that are available on Renovaro’s website at www.renovarobio.com

and on the website of the Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”) at www.sec.gov. All forward-looking statements

are based on assumptions that Renovaro and GEDi Cube believe to be reasonable but that may not prove to be accurate. Any forward-looking

statement speaks only as of the date on which such statement is made, and neither Renovaro nor GEDi Cube undertakes any obligation

to correct or update any forward-looking statement, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, except

as required by applicable law. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements, which speak

only as of the date hereof.

Important Additional Information Regarding

the Merger Will Be Filed with the SEC and Where to Find It

In connection with the proposed Transaction,

Renovaro intends to file a proxy statement (the “proxy statement”), and will file other documents regarding the proposed

Transaction with the SEC. INVESTORS AND SECURITYHOLDERS OF RENOVARO ARE URGED TO CAREFULLY AND THOROUGHLY READ, WHEN THEY

BECOME AVAILABLE, THE PROXY STATEMENT, AS MAY BE AMENDED OR SUPPLEMENTED FROM TIME TO TIME, AND OTHER RELEVANT DOCUMENTS FILED

BY RENOVARO WITH THE SEC BECAUSE THEY WILL CONTAIN IMPORTANT INFORMATION ABOUT RENOVARO, GEDI CUBE AND THE PROPOSED TRANSACTION,

THE RISKS RELATED THERETO AND RELATED MATTERS.

Once complete, a definitive proxy statement

will be mailed to the stockholders of Renovaro. Investors will be able to obtain free copies of the proxy statement, as may be

amended from time to time, and other relevant documents filed by Renovaro with the SEC (when they become available) through the

website maintained by the SEC at www.sec.gov. Copies of documents filed with the SEC by Renovaro, including the proxy statement

(when it becomes available), will be available free of charge from Renovaro’s website at www.renovarobio.com under the “Financials”

tab.

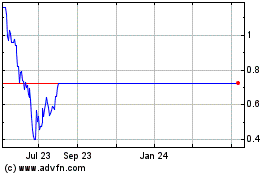

Enochian Biosciences (NASDAQ:ENOB)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2024 to May 2024

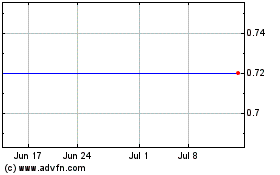

Enochian Biosciences (NASDAQ:ENOB)

Historical Stock Chart

From May 2023 to May 2024