Form DFAN14A - Additional definitive proxy soliciting materials filed by non-management and Rule 14(a)(12) material

November 20 2023 - 9:05AM

Edgar (US Regulatory)

UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

SCHEDULE 14A

(Rule 14a-101)

INFORMATION REQUIRED IN PROXY STATEMENT

SCHEDULE 14A INFORMATION

Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the

Securities Exchange Act of 1934

(Amendment No. )

Filed by the

Registrant ☐

Filed by a Party other than the Registrant ☒

Check the appropriate box:

| ☐ |

Preliminary Proxy Statement |

| ☐ |

Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as

permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) |

| ☐ |

Definitive Proxy Statement |

| ☒ |

Definitive Additional Materials |

| ☐ |

Soliciting Material Under Rule 14a-12

|

AIM IMMUNOTECH INC.

(Name of Registrant as Specified in Its Charter)

TED D. KELLNER

TODD

DEUTSCH

ROBERT L. CHIOINI

(Name of Persons(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if Other Than the Registrant)

Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box):

| ☐ |

Fee paid previously with preliminary materials |

| ☐ |

Fee computed on table in exhibit required by Item 25(b) per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11 |

Ted D. Kellner, Todd Deutsch

and Robert L. Chioini (the “Kellner Group”) have filed a definitive proxy statement and accompanying GOLD proxy card with the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) to be used to solicit votes for their

election to the Board of Directors of AIM Immunotech Inc., a Delaware corporation (the “Company” or “AIM”), at the 2023 Annual Meeting of Stockholders scheduled to be held on December 1, 2023.

Below is a copy of the public version of the post-trial brief filed by Mr. Kellner in connection with the pending litigation in the Delaware Court of

Chancery. Copies of all filings by parties to the litigation in the Delaware Court of Chancery are available from the Court’s docket. The Kellner Group may make this brief available to AIM stockholders commencing on November 20, 2023.

IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE

|

|

|

|

|

| TED D. KELLNER, |

|

) |

|

|

|

|

) |

|

|

| Plaintiff, |

|

) |

|

|

|

|

) |

|

|

| v. |

|

) |

|

C.A. No. 2023-0879-LWW |

|

|

) |

|

|

| AIM IMMUNOTECH INC. |

|

) |

|

PUBLIC VERSION FILED |

| THOMAS EQUELS, |

|

) |

|

NOVEMBER 18, 2023 |

| WILLIAM MITCHELL, |

|

) |

|

|

| STEWART APPELROUTH, and |

|

) |

|

|

| NANCY K. BRYAN, |

|

) |

|

|

|

|

) |

|

|

| Defendants. |

|

) |

|

|

|

|

) |

|

|

| |

|

) |

|

|

|

|

) |

|

|

| AIM IMMUNOTECH INC., |

|

) |

|

|

|

|

) |

|

|

| Counterclaim Plaintiff, |

|

) |

|

|

|

|

) |

|

|

| v. |

|

) |

|

|

|

|

) |

|

|

| TED D. KELLNER, |

|

) |

|

|

|

|

) |

|

|

| Counterclaim Defendant. |

|

) |

|

|

TED D. KELLNER’S POST-TRIAL BRIEF

OF COUNSEL:

Teresa Goody Guillén*

BAKER & HOSTETLER

LLP

1050 Connecticut Avenue, NW

Suite 1100

Washington, D.C. 20036

Marco Molina*

BAKER & HOSTETLER LLP

600 Anton Boulevard

Suite 900

Costa Mesa, California 92626

Jeffrey J. Lyons (#6437)

Michael E. Neminski (#6723)

BAKER & HOSTETLER LLP

1201 North Market Street, Suite

1407

Wilmington, Delaware 19801

(302) 468-7088

Ambika B. Singhal*

BAKER & HOSTETLER LLP

2850 N. Harwood Street, Suite

1100

Dallas, Texas 75230

Alexandra L. Trujillo*

BAKER & HOSTETLER LLP

811 Main Street, Suite 1100

Houston, Texas 77002

*Admitted pro hac vice

Dated: November 16, 2023

John M. Seaman (#3868)

Eric A. Veres (#6728)

Eliezer Y. Feinstein (#6409)

ABRAMS & BAYLISS LLP

20 Montchanin Road, Suite 200

Wilmington, Delaware 19807

(302)

778-1000

Attorneys for Plaintiff Ted D. Kellner

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Page(s) |

|

| Cases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| AB Value P’rs, LP v. Kreisler Mfg. Corp.,

2014 WL 7150465 (Del. Ch. Dec. 16,

2014) |

|

|

23, 26, 28 |

|

|

|

| ACP Master, Ltd. v. Sprint Corp.,

2017 WL 75851 (Del. Ch. Jan. 9, 2017) |

|

|

42 |

|

|

|

| Black v. Hollinger Int’l Inc.,

872 A.2d 559 (Del. 2005) |

|

|

38, 39 |

|

|

|

| BlackRock Credit Allocation Income Tr. v. Saba Cap. Master Fund, Ltd.,

224 A.3d 964

(Del. 2020) |

|

|

29, 56, 60 |

|

|

|

| Brown v. Matterport, Inc.,

2022 WL 89568 (Del. Ch. Jan. 10, 2022), aff’d,

2022 WL 2960331

(Del. July 27, 2022) (ORDER) |

|

|

40 |

|

|

|

| Candlewood Timber Gp. LLC v. Pan Am. Energy LLC,

2006 WL 1382246 (Del. Super.

May 16, 2006) |

|

|

54 |

|

|

|

| Chase Manhattan Bank v. Iridium Africa Corp.,

2003 WL 22928042 (D. Del. Nov. 25,

2003) |

|

|

54 |

|

|

|

| Chesapeake Corp. v. Shore,

771 A.2d (Del. Ch. 2000) |

|

|

37, 65 |

|

|

|

| Coster v. UIP Cos., Inc.,

300 A.3d 656 (Del. 2023) |

|

|

passim |

|

|

|

| Crown EMAK P’rs, LLC v. Kurz,

992 A.2d 377 (Del. 2010) |

|

|

38 |

|

|

|

| Delaware Board of Medical Licensure & Discipline v.

Grossinger,

224 A.3d 939 (Del. 2020) |

|

|

38, 39 |

|

|

|

| Durkin v. Nat’l Bank of Olyphant,

772 F.2d 55 (3rd Cir. 1985) |

|

|

29, 64 |

|

iv

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In re Ebix, Inc. S’holder Litig.,

2018 WL 3545046 (Del. Ch. July 17,

2018) |

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

| EMAK Worldwide, Inc. v. Kurz,

50 A.3d 429 (Del. 2012) |

|

|

23 |

|

|

|

| Emerald P’rs v. Berlin,

726 A.2d 1215 (Del. 1999) |

|

|

50 |

|

|

|

| Giuricich v. Emtrol Corp.,

449 A.2d 232 (Del. 1982) |

|

|

26 |

|

|

|

| Hill Int’l, Inc. v. Opportunity P’rs L.P.,

119 A.3d 30 (Del. 2015) |

|

|

40, 41 |

|

|

|

| Hollinger Int’l, Inc. v. Black,

844 A.2d 1022 (Del. Ch. 2004), aff’d,

872 A.2d 559 (Del. 2005) |

|

|

64 |

|

|

|

| Hubbard v. Hollywood Park Realty Enters., Inc.,

1991 WL 3151 (Del. Ch. Jan. 14,

1991) |

|

|

passim |

|

|

|

| Jorgl v. AIM ImmunoTech Inc.,

2022 WL 16543834 (Del. Ch. Oct. 28, 2022) |

|

|

passim |

|

|

|

| Mercier v. Inter-Tel (Del.), Inc.,

929 A.2d 786

(Del. Ch. 2007) |

|

|

37 |

|

|

|

| MM Cos., Inc. v. Liquid Audio, Inc.,

813 A.2d 1118 (Del. 2003) |

|

|

25 |

|

|

|

| Pell v. Kill ,

135 A.3d 764 (Del. Ch. 2016) |

|

|

28 |

|

|

|

| PennEnvironment v. PPG Indus., Inc.,

2013 WL 6147674 (W.D. Pa. Nov. 22, 2013) |

|

|

46 |

|

|

|

| Phillips v. Insituform of N. Am., Inc.,

1987 WL 16285 (Del. Ch. Aug. 27, 1987) |

|

|

34 |

|

|

|

| Rainbow Mountain, Inc. v. Begeman,

2017 WL 1097143 (Del. Ch. Mar. 23, 2017) |

|

|

40 |

|

v

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Robert M. Bass Grp., Inc. v. Evans,

552 A.2d 1227 (Del. Ch. 1988) |

|

|

27 |

|

|

|

| Roca v. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co.,

842 A.2d 1238 (Del.

2004) |

|

|

40 |

|

|

|

| Rosenbaum v. CytoDyn Inc.,

2021 WL 4775140 (Del. Ch. Oct. 13, 2021) |

|

|

29, 31, 40, 64 |

|

|

|

| Strategic Inv. Opportunities LLC v. Lee Enters.,

2022 WL 453607 (Del. Ch. Feb. 14,

2022) |

|

|

passim |

|

|

|

| Totta v. CCSB Fin. Corp.,

2022 WL 1751741 (Del. Ch. May 31, 2022) |

|

|

55 |

|

|

|

| Unitrin, Inc. v. Am. Gen. Corp.,

651 A.2d 1361 (Del. 1995) |

|

|

37 |

|

|

|

| Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum Co.,

493 A.2d 946 (Del. 1985) |

|

|

passim |

|

|

|

| Williams Cos. S’holder Litig.,

2021 WL 754593 (Del. Ch. Feb. 26, 2021) |

|

|

passim |

|

vi

Plaintiff and Counterclaim Defendant Ted D. Kellner (“Kellner” or

“Plaintiff”) hereby submits his Post-Trial Brief and argues as follows:

INTRODUCTION

Trial confirmed AIM ImmunoTech Inc. (“AIM”) stockholders should have the choice, at this year’s annual

meeting, to vote for Kellner, Todd Deutsch (“Deutsch”), and Robert Chioini (“Chioini”) for election to AIM’s board of directors (“Board”).

In August 2023, Thomas Equels (“Equels”), William Mitchell (“Mitchell”), Stuart Appelrouth

(“Appelrouth”) and Nancy Bryan (“Bryan” and, together with Equels, Mitchell, and Appelrouth, the “Defendants”) tried to deprive stockholders of that choice by rejecting Kellner’s nomination

notice (“Notice”). But the evidence confirms this rejection was made under onerous, vague, and bespoke advance notice bylaw provisions (“Bylaw Amendments”) that Equels, Mitchell, and Appelrouth (“Entrenched

Directors”) adopted months earlier to ensure they had the ability to reject any effort by dissident stockholders to run a proxy contest. The evidence also confirms that, once it was apparent that a proxy contest was underway, Defendants:

(i) tried to railroad this effort by adding last-ditch prompts to the D&O questionnaire designed to provide the Board with a pretext to deny the nominations; (ii) prejudged the Notice by calling it an illegal “hostile takeover” in

internal e-mails, draft releases, and public court filings before the Board assessed its validity; and (iii) and rejected the Notice under the Bylaw Amendments based on conspiracy theories

concocted by lawyers that Defendants took at “face value,” without independent inquiry, and that have since been debunked or abandoned.

This corporate democracy wrong can be righted, and stockholders’ sacrosanct right to

make directorial nominations can be restored, in three separate ways. First, the rejection can be vacated because the Bylaw Amendments are void as a matter of law. The record confirms that the Bylaw Amendments were not

adopted on a “clear day” but, rather, amid a thunderstorm. Voting data from 2022 demonstrates that the Entrenched Directors could not win a contested election and that they believed that another proxy contest was coming. In this

context, the Bylaw Amendments only survive if, under enhanced scrutiny, Defendants prove there was a compelling justification to respond to a legitimate threat to an important corporate interest the Bylaw Amendments were reasonably tailored to

address. Defendants failed to meet this burden because they have not and cannot identify a threat to a corporate interest—the only “threat” is to their Board seats—and because their adoption of fifty disclosure

prompts, most of which are bespoke, onerous, or vague, as well as requiring nominees to complete an overly burdensome D&O questionnaire, are the type of preclusive and coercive measures that cannot satisfy enhanced scrutiny review.

2

Second, Defendants’ rejection should be set aside because the Notice

complies with the bylaws. The 162-page Notice is fulsome in disclosing material facts about Kellner’s nominations. Defendants’ claims to the contrary are largely refuted by the plain text of the

Notice, which discloses the nominees’ ties to other stockholders who Defendants baselessly claim Kellner is “covering up.” Defendants abandoned most of their remaining rejection arguments at trial, such as their contention that

Kellner and Deutsch, the largest individual AIM stockholders, are engaged in an unlawful, covert scheme to depress AIM’s stock price by shorting it or by posting on internet message boards. And the remaining rejection theories were debunked at

trial such as that Kellner was behind the December 5, 2022 settlement negotiations among Chioini and AIM and that AIM stockholder Franz Tudor (“Tudor”) is the mastermind and Puppet Master of a cell-structured, hostile AIM

takeover involving myriad undisclosed individuals. Notably, Defendants did not call Tudor, nor any of the other individuals who Kellner is supposedly covering up, to testify at trial—and for good reason given their uncontroverted sworn

deposition testimony (submitted by Kellner at trial) that there is no conspiracy to take over AIM.

3

Third, Defendants’ rejection of the Notice can be set aside because it

was inequitable. Depriving Kellner of his sacrosanct right to nominate Board candidates only works if Defendants can prove that doing so advances a compelling corporate interest without coercing or precluding the stockholder voting franchise.

Defendants failed to meet this high burden and, instead, trial evidence confirms that Defendants stacked the deck against Kellner’s nominees by requiring myriad disclosures from them not required of their Board nominees, prejudging that those

disclosures were deficient before Kellner even made them, and outsourcing their duty to assess those disclosures to the same lawyers to whom Defendants had written a blank check to pursue an “offensive litigation strategy” against

stockholders.

If unchecked, Defendants’ actions would reduce the sacrosanct right to nominate directorial candidates to sacrilege,

whereby stockholders are subjected to litigation and libelous accusations simply for wanting to have the choice to vote for non-incumbent directors. For these reasons and those included below, Kellner asks

that judgment be granted against Defendants and that the counterclaims be denied in their entirety.

| |

A. |

The Embattled Board Cannot Win a Contested Election |

The proverbial elephant in the room is that the incumbent Board cannot win a contested election. This is evident from preliminary proxy voting

data from 2022, which confirms that stockholders would have replaced incumbent directors by a landslide if given the opportunity (JX0450), and the tally from the 2022 uncontested election where Mitchell and Appelrouth received almost twice as many

“Withhold” than “For” votes and where approximately 84% of shares did not vote for any of the Entrenched Directors (JX0475).

4

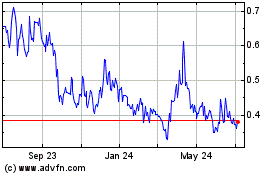

The facts driving stockholder discontent are undisputed. AIM’s stock price has declined

by 99% since 2016, when the Entrenched Directors gained Board control. JX0901. Over that period AIM has failed to obtain regulatory approvals necessary for AIM to commercialize its flagship drug, Ampligen (JX0701 at

3-5, 6- 7; JX1241) (of 19 clinical studies listed for Ampligen, 4 were terminated, 4 were suspended, 2 were withdrawn, and 1 reached Phase 3). It is, too, undisputed that although AIM raised nearly

$50 million in cash since 2020, only a small fraction has been used for clinical studies necessary to obtain regulatory approvals for Ampligen (Chioini Tr. 135, 140) and the majority of that cash has been used to pay millions to executives and

directors and law firms the Board hired to sue its stockholders. Deutsch Tr. 211; Appelrouth Tr. 699-700. Defendants also do not dispute that AIM will run out of cash by 2024 and currently has no plan to

obtain more financing to continue Ampligen trials. Mitchell Tr. 648-49; Appelrouth Tr. 702. Finally, it is undisputed that AIM failed to commercialize Alferon N Injection, its only drug with the

requisite regulatory approvals. JX0701.

5

Defendants failed to contest that the Board will not survive a proxy contest. Defendants

conceded Glass Lewis and Institutional Shareholder Services (“ISS”) have recommended against incumbent directors since 2021 and that there is “a very good chance” stockholders would have replaced the Board if given a

choice in 2022. Equels Tr. 565-66; Rodino Dep. 67.

There is no evidence that Defendants are doing

anything to win stockholder favor. The Board has effectively insulated itself from the stockholders, calling them “stalkholders” and “trolls,” suing them, and urging a Congresswoman, a Senator, and the Securities

and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) to investigate AIM’s largest individual stockholders. Equels Tr. 565-66; Rodino Dep. 67; JX1113; JX1114; JX0417 at

160-63; JX0720; JX0724; JX0727.

The only stockholder outreach the Board attempted occurred on

November 9, 2022, via a press release just after the 2022 annual stockholder meeting responding to stockholder feedback, promising to add two new directors and hire an independent compensation consultant to review executive-compensation packages

that had been soundly condemned by 84% of stockholders in the “say-on-pay” vote. JX0487; JX0474. But these were empty promises.

6

The record proves the Board had no intention of working with stockholders to add directors.

Chioini testified that he and Michael Rice (“Rice”)—whom AIM’s stockholders would have added to the Board if given the chance last year—viewed that press release as an “olive branch” and instructed their

counsel, John Harrington (“Harrington”), to request Defendants’ counsel, Michael Pittenger (“Pittenger”), to have the Board consider appointing them or “mutually agreeable” directors as part of an

effort to resolve outstanding disputes. Chioini Tr. 20; Harrington Tr. 385. But counsel never shared this proposal with the entire Board until August 2023, Pittenger Tr. 763, and AIM’s counsel and Equels instead weaponized and mischaracterized

it in myriad ways. Ultimately, the Board appointed only one new director, Defendant Bryan, who has known Equels for years and who has demonstrated no willingness to check the Entrenched Directors.

The compensation-review promise fared no better. The consultant AIM hired confirmed Equels receives a higher salary and more total cash than

other CEOs of biopharma companies that generate far more revenue than AIM, yet the Board has no plan to lower any executive’s salary, even while AIM’s cash crunch intensifies. Mitchell Dep. 99-100.

Defendants do not explain why they refuse to reduce Equels’s compensation. Nor do they contest Deutsch’s testimony that Equels demands to be paid millions in cash to support a lifestyle he enjoyed as a trial lawyer before joining AIM.

Deutsch Tr. 156. All of this underscores Defendants’ prioritization of their interests ahead of stockholders’ interests.

7

| |

B. |

The Board Amends the Bylaws Ahead of an Anticipated Proxy Contest |

Because they cannot win a contested election and because they do not want to relinquish their self-enrichment, the Entrenched Directors

unanimously voted, on March 28, 2023, to adopt the onerous Bylaw Amendments, so that the Board could reject attempted stockholder nominations. JX0679.

Defendants admit the Board did this in response to the perceived threat of a forthcoming proxy contest. Equels and Pittenger testified that

the Board adopted the Bylaw Amendments because it believed “some formulation” of stockholders who supported last year’s proxy contest would “go forward with a nomination attempt in 2023.” Equels Tr. 569-70, 624; Pittenger Tr. 712. Similarly, Pittenger’s March 17, 2023 memo and AIM’s March 20, 2023 Board meeting minutes recognize that the Board asked counsel to prepare the Bylaw Amendments

“[i]n response to significant activist activity during 2022” (JX0633 at 1) and to “better ensure” that the Board could reject nominations made by dissident stockholders whom the Board perceived to have been involved in last

year’s proxy contest (JX0646 at 2).

Take Section 1.4(c)(1)(D) (“AAU Provision”), which requires disclosure of

all current arrangements, agreements, or understandings (“AAUs”) relating to the nominations and all prior AAUs from the past 24 months. Equels proposed the 24- month lookback to capture AAUs related to

last year’s attempted nominations by former AIM stockholder Jonathan Jorgl (“Jorgl”). Equels Tr. 575. He did so based on speculation that (1) Jorgl and his group failed to disclose AAUs as part of a multi-

year conspiracy to take over AIM and loot its assets and (2) any future nomination efforts by any alleged “co-conspirators” must be an extension of the supposed 2022 conspiracy. Id.

8

The 24-month lookback is outside of the industry

norms. Plaintiff’s expert, Andrew Freedman (“Freedman”), testified this type of bylaw provision is highly unusual. Freedman Tr. 834-35 (“We found that no companies in the core sample

set contained a two-year look-back period.”); PX2 at 10. Defendants’ expert, Professor Edward Rock (“Rock”), conceded that this lookback is “bespoke,” “an interesting

innovation,” and not “current market practice.” Rock Tr. 807-08. And even AIM’s General Counsel, Peter Rodino (“Rodino”), testified that the length of this lookback period

was “arbitrary.” Rodino Tr. 489.

Notably, the AAU Provision is just one of fifty new disclosure prompts and obligations

imposed on stockholders under the Bylaw Amendments. JX0686 at 2- 5 (pp. 4-11 of SEC filing). These are too numerous to itemize here. Below are some of the more onerous, vague, bespoke, and arbitrary

provisions:

9

| |

1. |

Section 1.4(c)(1)(E) (the “Consulting/Nomination Provision”) requires disclosure of AAUs

between the nominating stockholder or a “Stockholder Associated Person” (“SAP”), on one hand, and any stockholder nominee, on the other hand, regarding consulting, investment advice or a previous nomination with respect to

publicly traded companies within the last ten years. JX0686 at 2. None of the bylaws in Rock’s core sample set or Freedman’s expanded set contain the Consulting/Nomination Provision (PX2 at

25-26), which Freedman opined is “egregious,” “overbroad,” and lends to “subjective” interpretation. Freedman Tr. 846. Rock did not opine that the SAP definition was consistent

with market practice and confirmed that he never examined the “content” of this provision. Rock Tr. 813. |

| |

2. |

Section 1.4(c)(1)(H) (the “First Contact Provision”) requires disclosure of the dates of

first contact among those involved in the nomination effort. JX0686 at 2. Once again, none of the bylaws in Rock’s core sample set or Freedman’s expanded sample set contain the First Contact Provision. PX2 at 25-26; Freedman Tr. 847. Freedman concluded that the First Contact Provision is “egregious” and “goes well beyond the type of information that is important or necessary for stockholders to render an

informed decision in an election contest.” Freedman Tr. 847. |

10

| |

3. |

Section 1.4(c)(3)(B) (the “Competitor Interest Provision”) is a run-on sentence of 1,099 words and 13 sub-parts, requiring disclosures concerning AIM stock, including derivative or short positions, and the stock of “any principal

competitor of” AIM, which is undefined. JX0686 at 3. This provision extends this disclosure prompt beyond stockholder nominees to “any member of the immediate family of such Stockholder Nominee, or any person acting in concert with such

Stockholder Nominee.” Id. at 2. The Competitor Interest Provision is, by Defendants’ admission, “complex.” Pittenger Tr. 730. Freedman determined that it is “quite rare” as it appeared only three times in his

sample set. Freedman Tr. 847. |

| |

4. |

Section 1.4(c)(4) (the “Known Supporter Provision”) requires disclosure of names and

addresses of stockholders or SAPs “known to support” the nominations. JX0686 at 4. None of the bylaws in Rock’s core sample set contain a Known Supporter Provision. Rock Tr. 815. Freedman opined that these are not “state-of-the-art” provisions, but highly “subjective” and “way too open-ended” where, as here, they are

“not couched in more specific terms such as known financial support.” Freedman Tr. 839-40. |

11

| |

5. |

Section 1.4(c)(1)(L) (the “D&O Questionnaire Provision”) requires nominees to

complete a D&O questionnaire. JX0686 at 3. While that is neither uncommon nor inherently problematic, “the devil is in the details.” Freedman Tr. 835. This provision gives AIM five business days (instead of the 1-2-business-day industry standard) to send the questionnaire. Id. at 836. As Freedman testified, a company may use the time it

gives itself to make “bespoke” revisions. Id. That is precisely what happened here: AIM significantly revised its questionnaire after Kellner requested it. Equels Tr.

582-87. And, as Rock admitted, AIM’s questionnaire is also egregious because it imposes a category of questions on stockholder nominees that does not apply to director nominees. Rock Tr. 811-12. |

Viewed in their totality, the Bylaw Amendments are “not commonplace or

consistent with market practice. They are overreaching . . . and contrary to shareholder democracy.” Freedman Tr. 832. As Freedman also explained: AIM’s “Board threw ‘everything but the kitchen sink’ into the [Bylaw

Amendments] in order to make it more difficult and expensive for shareholders to nominate” candidates for election. JX0985 ¶¶50, 102; see also JX0657 (a redline of the Bylaw Amendments against prior Bylaws).

| |

C. |

The Board Exempted Bryan from the Onerous Disclosure Requirements |

At trial, Defendants argued that the Bylaw Amendments were enacted not for entrenchment purposes, but rather to ensure the Board and

stockholders have all the material information in advance of the annual stockholder meeting. But if that were true, Defendants would have requested the same information from Bryan prior to her Board appointment on March 28, 2023 (the same

day the Bylaw Amendments were implemented). That never happened.

12

In March 2023, as the Board finalized its multi-month bylaw overhaul to require significant

candidate disclosures, it merely required Bryan to: (i) disclose biographical information (e.g., a resume); (ii) sit for short interviews; and (iii) submit a watered-down version of the stockholder D&O questionnaire.1 Bryan Tr. 669. But the D&O Questionnaire did not apply to Bryan: AIM already decided to name her a director days before receiving her completed questionnaire. JX1121; JX0673. To be

sure, neither that questionnaire nor any other questionnaire Bryan has since completed asks her to disclose information required from stockholder nominees. Bryan has not had to disclose AAUs she may have had concerning AIM or other public companies,

financial interests she may have with AIM or its competitors, the dates of first contact with Equels or others, or the full names and addresses of her family members and associates.

| 1 |

AIM’s securities counsel helped Bryan complete the questionnaire, despite her outsider status. Bryan Tr. 669-70. Kellner, Deutsch, and Chioini received no such assistance. |

13

As Rodino (AIM’s General Counsel) testified, this disparate treatment does not serve

the purpose of ensuring that the Board and stockholders have all relevant information as to all directorial nominees before an election. Specifically, Rodino testified that Board members should be subject to the same disclosure

requirements as stockholder nominees “so that everybody was [sic] on equal footing” and “current board members wouldn’t be held to a different standard as to any other new additional nominees” as that would be the

only “fair” electoral process. Rodino Tr. 490-91. The Board, however, ignored his advice and instead rubberstamped Bryan’s candidacy while at the same time imposing an unprecedented gauntlet of

disclosures on all future stockholder nominees.

| |

D. |

Kellner and His Group Take a Stand |

Around April 2023, soon after the Board adopted the Bylaw Amendments, Kellner and Deutsch considered a proxy contest. Kellner and Deutsch are

AIM’s largest individual stockholders. Deutsch Tr. 158. They were previously reluctant to partake in a proxy contest for AIM and, in fact, had never participated in any such contest for any company, despite being seasoned investors in hundreds

of public companies. Kellner Tr. 260; Deutsch Tr. 153. But they believe that the Entrenched Directors are stockholder “bullies” and understood that if they did not push back no one else would (or could). Deutsch Tr. 188, 208; Kellner Tr.

209.

14

Kellner testified he did not pay close attention to AIM, despite owning stock since 2021,

because his AIM holding was a small portion of his net worth. Kellner Tr. 240, 244. But that began changing last year when AIM sued him, Deutsch, and others in Florida federal court alleging federal-securities law violations for being part of a

supposed undisclosed stockholder group trying to take over AIM (“Florida Action”). Kellner Tr. 245. Kellner was also haled into this Court by AIM as a third- party witness in the litigation related to Jorgl’s attempted proxy

contest (“Jorgl Action”). Id. at 247. These occurrences and AIM’s abysmal financial performance prompted Kellner to attend AIM’s 2022 annual stockholder meeting. Id. at 224. At that meeting, Equels and the

rest of the Board refused to meaningfully interact with Kellner causing Kellner to leave that meeting very upset. Id. at 226-28.

In ensuing months, Kellner conducted diligence as to the 2022 proxy contest and inquired as to whether Jorgl or some other stockholder was

considering another contest in 2023. Kellner Tr. 228-30. After learning from Chioini, whom he first met in late 2022, that there were no such plans, Kellner intensified his diligence into AIM. Id. He

understood that a proxy contest would be difficult, especially given the unprecedented and oppressive bylaw-provision overhaul. Id. at 232-34. But Kellner wanted to proceed with a proxy contest because

he knows can help turn AIM around, given his track record in overseeing businesses and generating stockholder value, and because it was the right thing to do:

15

Q. [W]hy go forward with this if the situation is what you just described?

A. Sometimes I ask myself that question. It’s, as I said, I consider myself a real principled guy. And every business I’ve been in,

I’ve brought in and been very fair to partners. And I treat people fairly. And I would say the vast, vast majority of the companies that I’ve invested in and the people I’ve partnered with have been that: principled, ethical, and done

things to benefit the former shareholder. That has been the antithesis in this investment But I’m spending a lot of money, personal money, to fight what I think is right for shareholders. All I’m asking for is a right to vote. If I lose,

we lose. If we win, we win. That[] simple.

Id. at 233-35.

Similarly, Deutsch testified that he accepted Kellner’s nomination because he was fed up with how the Board treated stockholders and

ruined the company and because he has the know-how and network to get AIM back on track. Deutsch Tr. 158-160. Deutsch explained that, as AIM’s largest individual

stockholder, he tried to help management when AIM’s stock was plummeting but was rebuffed. Id. at 155-156. Deutsch’s frustration increased when Equels told him that, despite the plummeting

stock (which cost Deutsch millions), Equels refused a paycut because he needed a multi-million dollar salary to match what he earned in his prior job. Id. at 156. This frustration intensified when AIM sued Deutsch in the Florida Action and

amended the Bylaws to thwart a proxy contest. Id. at 157-58. Similar to Kellner, Deutsch became interested in partaking in a proxy contest to vote the “bullies” out. Id. at 207-11.

16

Chioini similarly accepted Kellner’s nomination because it was the right thing to do

for AIM and its stockholders. Specifically, Chioini testified that Ampligen has the potential to save lives but has been mismanaged. Chioini Tr. 135, 140. His vast experience running clinical trials and obtaining regulatory approvals for biopharma

products would fill a large need for AIM. Id. at 8, 42. And he felt responsibility to help AIM’s stockholders, who overwhelmingly supported his candidacy last year. Id. at 15.

On July 24, 2023, Kellner requested a copy of the D&O Questionnaire from AIM. JX0821 at 2-3.

Days later, Kellner and Deutsch filed a Schedule 13D with the SEC to disclose their intent to work as a stockholder group as to AIM. JX0831. On August 4, 2023, Kellner timely submitted his Notice and attachments, 162 pages in total, in compliance

with the Bylaws. JX0871.

| |

E. |

Defendants Railroaded Kellner’s Nomination Efforts, Prejudged the Notice, and Rejected It for

Pretextual Reasons |

The evidence confirms that Defendants and their counsel attempted to railroad Kellner’s

nominations by adding last-ditch revisions to the D&O questionnaire. As noted, AIM had up to five business days to send the questionnaire when requested. JX0686. During that time, Equels worked with counsel, Potter Anderson & Corroon

(“Potter”) and Kirkland & Ellis (“K&E”), to revise the D&O questionnaire twice, adding 15 pages of disclosure prompts. JX1226; JX0834; JX0841. Specifically:

17

| |

1. |

On July 28, 2023, Potter added, inter alia, a requirement that a potential nominee disclose whether

ISS or Glass Lewis had ever issued an adverse recommendation in connection with the nominees’ director candidacy to a public company board. JX0834; Equels 582-83. This added a new Section VI that only

applied to stockholder nominees. Equels Tr. 584-85. |

| |

2. |

On July 30, 2023, K&E circulated a second round of revisions, JX0841, adding a requirement that, in

addition to disclosing the AAUs required by the Bylaw Amendments, Kellner and his nominees also had to disclose “preliminary” discussions with third parties about the nominations, even if they had not resulted in AAUs. JX0841.

|

AIM returned this drastically revised questionnaire to Kellner on the fifth day of the window (July 31, 2023)2 (JX1226), leaving Kellner and his nominees only three business days to complete the 43-page D&O questionnaire before the deadline. Notwithstanding the

substantial effort by Kellner and his group to disclose all material information required by the Bylaws and the D&O questionnaire, the record confirms that the Board at all times viewed Kellner’s nominations as being “dead on

arrival.”

| 2 |

The nomination window opened July 7, 2023. JX0686 at 1-2.

|

18

First, the evidence confirmed that on July 31, 2023—five days before

Kellner submitted his Notice—Equels asked to speak to each Director to convey his belief that a “second attempted hostile takeover” of AIM was afoot. Equels Tr. 596-97.

Second, the evidence confirmed that on August 7, 2023—the day before the Board first met to discuss the

Notice and more than two weeks before the Board rejected the Notice—AIM filed a motion in the Florida Action characterizing the Notice deficient because, inter alia, it failed to account for shares controlled by Kellner and

his group and because it was part of an illegal take-over attempt. Equels Tr. 599-602.

Third, the evidence confirmed that, on August 7, 2023, AIM began preparing a press release announcing that the Notice was

materially deficient and suggesting that it would be rejected. Equels Tr. 605-06. When confronted with this release, Equels claimed it reflected “contingency” planning. Id. at 607-08. Equels, however, admitted that AIM did not draft a separate press release for the “contingency” of approval. Put differently, the Board’s rejection was a fait accompli. Id. at

610.

Although the Board knew it would reject the Notice, it still met three times between August 8 and August 22 before voting,

on August 22, to reject it. JX0882; JX0911. On August 23, the Board sent Kellner a letter with the bases for rejection. JX0918.

19

The evidence confirms the rejection was pretextual. Defendants outsourced their obligation

to review this Notice to outside counsel even though this review was almost wholly factual in nature. Equels Tr. 594-95; Mitchell Tr. 644; Bryan Tr. 660; Appelrouth Tr.

692-93. When counsel informed them of supposed deficiencies, Defendants took those representations “at face value” and conducted no independent investigation. Mitchell Tr. 643-45; Bryan Tr. 667; Appelrouth Tr. 692-93; Equels Tr. 594-95. Moreover, all of the so-called

deficiencies counsel cited and the Board relied upon have since been debunked or abandoned. For example, Defendants have failed to substantiate the allegation that Kellner and his group are engaging in stock manipulation to depress AIM’s stock

price (JX0909), and Deutsch resoundingly refuted that allegation at trial. Deutsch Tr. 164-65. The same is true of the allegation that Kellner and his group failed to disclose that they are posting under

aliases in internet message boards to disparage management. This was debunked in non-party discovery, which confirmed that neither Kellner nor anyone affiliated with him made the posts. Defendants also

abandoned this position. Id. at 164-65. The same is true of the allegation that the Notice was deficient because Chioini failed to disclose “his principal occupation or employment [] during at

least the time period spanning from five years prior to the date of the Notice (August 4, 2018) through the founding of his consultancy business . . . at some point in 2019.” JX0918 at 8. Chioini confirmed there was nothing to disclose: he took

six to eight months off for back surgery after leaving Rockwell Medical in 2018. Chioini Tr. 7-8.

20

This “shoot first, ask questions later” approach is unacceptable. Defendants

failed to give the Notice its due consideration and instead rejected it for arbitrary and baseless reasons, as further analyzed in Argument Section II, infra.

| |

F. |

Defendants Put Their Interests Ahead of Stockholder Interests |

Defendants suggested that the Notice was rejected to protect the interests of the stockholders. But evidence confirms the exact opposite.

Rejecting the Notice was contrary to the interests of AIM’s largest individual stockholders, Kellner and Deutsch, and the interests of most of the remaining stockholders who refused to vote for the incumbent directors last year. JX0450.

Defendants are also hemorrhaging investor capital. Defendants authorized the retention of not one but two law firms to assess

the Notice and run an “offensive litigation strategy” against stockholders. Equels Tr. 615-16; Appelrouth Tr. 698-99; JX0909. In so doing, the Board agreed to

authorize all future payments to these law firms without seeing litigation budgets, negotiating discounts or instituting fee caps, or having any clue as to how much these law firms charge. Appelrouth Tr.

699-700. According to AIM’s proxy materials filed with the SEC days after trial ended, AIM estimates that it will spend $7.8 million in connection with those legal efforts on top of the over

$5 million it spent last year for similar efforts. AIM ImmunoTech Inc. Proxy Statement (Schedule 14A) (Nov. 6, 2023) at 27. In other words, in one year, AIM will have spent more than $12.8 million

for the sole purpose of preventing a contested election, because its Board is incapable of winning one.

21

Appelrouth admitted that if AIM runs out of cash it cannot run clinical trials for Ampligen

and that, without such trials, AIM will not obtain regulatory approvals needed for commercialization. Appelrouth Tr. 701-02. Mitchell testified the Board anticipated that AIM had more than $20 million in

its treasury and that, based on that estimate, AIM had just enough cash to run clinical trials through 2024. Mitchell Tr. 649. But AIM’s recent Form 10-Q confirms that, due to overspending on lawyers and

compensation, AIM is down to about $15 million in cash. Additional losses are expected as the Board continues its Rambo-style litigation tactics, as evident by a recent appeal by AIM in the Florida Action and a letter from K&E indicating

that AIM is pursuing unnamed claims against stockholders to recover unnamed damages. AIM ImmunoTech Inc. Quarterly Report (Form 10-Q) (Nov. 14, 2023) at 2.

For these reasons, there is no basis for Defendants’ contention that the Board’s actions are in the best interests of stockholders.

In reality, unless stockholders are given the opportunity to vote for new directors, Defendants’ depletion of stockholder value may be irreversible.

22

ARGUMENT

Plaintiff is entitled to judgment in his favor for three separate and independent reasons. First, the Bylaw Amendments are

facially invalid because the Entrenched Directors adopted them for an inequitable purpose in violation of their fiduciary duties. Second, even if the Bylaw Amendments are facially valid, the Notice complied with them. Third, even if the Notice did

not comply with the Bylaw Amendments, non-compliance is excused because the Board’s rejection of the Notice was inequitable and without valid corporate purpose. Each of these grounds independently compels

judgment in Kellner’s favor.

| I. |

THE BYLAW AMENDMENTS WERE INVALID WHEN ADOPTED |

| |

A. |

Defendants Breached Their Fiduciary Duties |

Stockholders have a right to “vote for the directors that [they] want[ ] to oversee the firm.” EMAK Worldwide, Inc. v. Kurz,

50 A.3d 429, 433 (Del. 2012). This embraces the right to nominate a competing slate. Hubbard v. Hollywood Park Realty Enters., Inc., 1991 WL 3151, at *5 (Del. Ch. Jan. 14, 1991). Here, Defendants acted “to make compliance impossible or

extremely difficult, thereby thwarting the challenger entirely.” AB Value P’rs, LP v. Kreisler Mfg. Corp., 2014 WL 7150465, at *3 (Del. Ch. Dec. 16, 2014). They admit they targeted “Jorgl, Chioini, Tudor, and others” they

believe were “engaged in 2022” efforts at corporate change. DPTB at 25. That is a paradigmatic “selfish [and] disloyal” act. Coster v. UIP Cos., Inc., 300 A.3d 656, 672 (Del. 2023) (“Coster II”).

23

| |

1. |

Enhanced Scrutiny Applies |

Given “the inherent conflicts of interest that arise when a board of directors acts to prevent shareholders from effectively exercising

their right to vote … enhanced scrutiny … is the appropriate standard of review to apply in this case.” Strategic Inv. Opportunities LLC v. Lee Enters., 2022 WL 453607, at *15 (Del. Ch. Feb. 14, 2022). By enacting the Bylaw

Amendments, the Board “interfere[d] with a corporate election or a stockholder’s voting rights in contests for control.” Coster II, 300 A.3d at 672. Defendants perceived the 2022 proxy contest to be ongoing. Equels Tr. 624;

Pittenger Tr. 712; Mitchell Dep. 188-90. Equels’s February 2023 affidavit in the Florida Action attested that the same 2022 “Group” was “already threatening to revive their efforts this

year.” JX0600 at 5. Defendants cited the December 5, 2022 call between Harrington and Pittenger in court and corporate filings as proof of continued conflict. See, e.g., JX0600. JX0601, JX940, JX0948. As of March 2023, “the

skies were cloudy, and it was raining,” given that Defendants “faced a serious” electoral challenge. Coster II, 300 A.3d at 664. That fact triggers enhanced scrutiny.

24

Undeterred, Defendants invoke the business judgment rule. Defendants’ Pre- Trial Brief

(“DPTB”) at 40. But “judicial review under the deferential traditional business judgment rule standard is inappropriate when a board of directors acts for the primary purpose of impeding or interfering with the effectiveness of

a shareholder vote.” MM Cos., Inc. v. Liquid Audio, Inc., 813 A.2d 1118, 1128 (Del. 2003). This “will be true in every instance in which an incumbent board seeks to thwart a shareholder majority” vote. Id. (citation

omitted). In a “contest for control,” “[a] board’s unilateral decision to adopt a defensive measure touching ‘upon issues of control’ that purposefully disenfranchises its shareholders is strongly suspect under

Unocal.” Coster II, 300 A.3d at 668. This principle “recognize[s] the inherent conflicts of interest that arise when a board of directors acts to prevent shareholders from effectively exercising their right to vote either

contrary to the will of the incumbent board members generally or to replace the incumbent board members in a contested election.” Lee Enters., 2022 WL 453607, at *15.

25

Because the Bylaw Amendments were defensive measures in response to “significant

[stockholder] activist activity during 2022,” JX0643; Equels Tr. 573, the business judgment rule does not apply. Defendants knew opposing candidates likely would have won in 2022 had they been on the slate. JX0450; Rodino Dep. 67. And the Bylaw

Amendments were adopted “[i]n response to significant activist activity during 2022 in which an activist group attempted to nominate director candidates.” JX0633 at 1; see also JX0646. Also, the Bylaw Amendments’ vagueness and

burden make compliance “impossible or extremely difficult.” AB Value P’rs, 2014 WL 7150465, at *3. Because “the right to vote for the election of successor directors has been effectively frustrated,” the Court must

apply “careful judicial scrutiny.” Giuricich v. Emtrol Corp., 449 A.2d 232, 239 (Del. 1982).

Defendants argue that

“Kellner cannot invoke enhanced scrutiny … [because he] denied making any … threat” in December 2022. DPTB at 40 n.14. But the question is not whether a specific stockholder threatens a proxy contest, but whether the board took

“defensive measures in response to a perceived threat.” In re Ebix, Inc. S’holder Litig., 2018 WL 3545046, at *7 (Del. Ch. July 17, 2018) (emphasis added). That standard looks to Defendants’ view of events, and

they understood a threat to their own seats.

| |

2. |

Defendants Have Not Satisfied Their Exacting Burden Under Enhanced Scrutiny

|

Under enhanced scrutiny, “the board bears the burden of proof.” Coster II, 300 A.3d at 672.

Defendants must identify “a compelling justification for [their] action” and prove that “the board faced a threat ‘to an important corporate interest or to the achievement of a significant corporate benefit.’” Id.

at 671-72. Then they must show their response “tailor[ed] . . . to only what is necessary to counter the threat.” Id. at 673. Defendants fail at both steps with respect to the adoption of

the Bylaw Amendments.

26

| |

a. |

Defendants Fail to Identify a Real Threat to an Important Corporate Interest

|

Defendants do not articulate a coherent justification for adopting the Bylaw Amendments. Though they say much, their

contentions “resemble[] more a slogan than a reasoned legal argument.” Robert M. Bass Grp., Inc. v. Evans, 552 A.2d 1227, 1240 (Del. Ch. 1988). In various iterations, Defendants propose interests in thwarting a “hostile

takeover,” ensuring disclosure, modernizing AIM’s bylaws, and implementing advice of counsel. None of these assertions works.

Hostile Takeover Theory. Defendants employ the phrase “hostile takeover” often. See, e.g., DPTB at 1. But they never

say how Kellner’s Notice presented a threat to “an important corporate interest or to the achievement of a significant corporate benefit.” Coster II, 300 A.3d at 672. “Many forms of stockholder activism can be beneficial

to a corporation” (Williams Cos. S’holder Litig., 2021 WL 754593, at *29 (Del. Ch. Feb. 26, 2021)), and “the stockholders—not the Board or this court—should decide the path for AIM” (Jorgl v. AIM ImmunoTech

Inc., 2022 WL 16543834, at *17 (Del. Ch. Oct. 28, 2022)).

27

Defendants’ position counts against them. They aver the Bylaw Amendments targeted

“the group” involved “with a takeover attempt” in 2022 (DPTB at 38), they defend the 24-month lookback with evidence of “a great deal of activity, probably almost up to 18 months prior

to the actual nomination, a year to 18 months” (Equels Tr. 529-30), they declare the point was to thwart “activists or hostile acquirors” (id. at 522), and so forth. But Defendants are

not entitled to decide certain individuals are poor board candidates and exclude them from the ballot or make their nomination “impossible or extremely difficult.” AB Value P’rs, 2014 WL 7150465, at *3. A perceived “threat

cannot be justified on the grounds that the board knows what is in the best interests of the stockholders.” Coster II, 300 A.3d at 672; see also Pell v. Kill, 135 A.3d 764, 790 (Del. Ch. 2016). And it certainly cannot be justified

on the grounds that Defendants would prefer retaining power. Yet Defendants’ brief and trial presentation amount to just that.

Grasping at straws, Defendants take from the hostile-tender-offer playbook, repeatedly insisting they needed to prevent a takeover

“without a control premium.” DPTB at 62; Pittenger Tr. 749. That has nothing to do with “the free exercise of the stockholder vote as an essential element of corporate democracy.” Coster II, 300 A.3d at 672. Board seats

are not bought and sold, so the assertion is gobbledygook. A board’s interest in obtaining a control premium arises from a “coercive tender offer” that is “designed to stampede shareholders into tendering” at an initial

offering price, “even if the price is inadequate, out of fear of what they will receive at the

28

back end of the transaction.” Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum Co., 493 A.2d 946, 956 (Del. 1985). That is not the case here because there is no analogy between board elections and

manipulative tender offers. Defendants have no interest in protecting stockholders from their own voting choices: “To allow for voting while maintaining a closed candidate selection process thus renders the former an empty exercise.”

Hubbard, 1991 WL 3151, at *6 (quoting Durkin v. Nat’l Bank of Olyphant, 772 F.2d 55, 59 (3rd Cir. 1985)).

Disclosure Theory. Defendants also aver the Bylaw Amendments serve key disclosure objectives. See DPTB at 2, 36, 41. But their

defense of “[a]dvance notice bylaws” in the abstract (id. at 36), does not speak to the Bylaw Amendments adopted in March 2023. The authorities Defendants cite (DPTB at 36-37, 42), all address

bylaws “validly enacted on a clear day.” Lee Enters., 2022 WL 453607, at *18; Rosenbaum v. CytoDyn Inc., 2021 WL 4775140, at *2 (Del. Ch. Oct. 13, 2021) (same); BlackRock Credit Allocation Income Tr. v. Saba Cap. Master

Fund, Ltd., 224 A.3d 964, 980 (Del. 2020) (same); Jorgl, 2022 WL 16543834, at *14-16 (same). No precedent gives boards carte blanche to adopt whatever advance-notice bylaws they desire to

frustrate challenges to their reelection.

29

Thus, enhanced scrutiny requires more than vague references to disclosure. It requires a

“threat” that is “real and not pretextual.” Coster II, 300 A.3d at 672. But the threat here was not real and the purpose was pretextual. The supposed threat from 2022 had been resolved under AIM’s prior bylaws to

Defendants’ complete satisfaction. See, e.g., Equels Tr. 576 (admitting “the previous version of the bylaws was sufficient to protect AIM”). Defendants’ overhaul of bylaws that already served their supposed disclosure

purpose was, thus, pretextual. And their announcement that they targeted a “group” of stockholders proves they were “principally motivated to interfere with the election of directors for selfish reasons.” Coster II, 300

A.3d at 665. Moreover, it is clear that directors fresh off a proxy contest they would have lost (if stockholders had a choice), and expecting another contest, acted selfishly in upending the election system by targeting their perceived competitors.

Defendants’ disclosure theory also lacks credibility where the Board and stockholders have comparatively little information on

incumbents. Yet that is the case here as evidenced by the fact that the Board did not require Bryan to make most of the disclosures required of stockholder nominees. This disparity underscores that Defendants enacted the Bylaw Amendments not because

they want future board nominees to disclose information but, rather, because they want to make it harder for stockholders to make nominations in the first place.

30

Modernization Theory. Defendants next contend that their purpose was to

“modernize” AIM’s bylaws. See, e.g., Equels Tr. 522. But Defendants admitted that, in promulgating the Bylaw Amendments, they never reviewed other public company’s bylaws. JX0948 at

39-40. Defendants cannot rely on post hoc rationalizations now. CytoDyn, 2021 WL 4775140, at *21.

Moreover, that interest is invalid. The updates to technical mechanics (like electronic-communication provisions) and those addressing legal

developments (like forum-selection provisions) are not at issue. Rather, as Defendants wield this concept, modernization describes corporate defense-side practices to thwart activists. See Rock Tr.

818-19. According to Defendants, a corporation modernizes its bylaws by making them like other corporations’ bylaws, which reflects nothing but the role “[c]orporate counsel plays…in the

propagation and the development of market practices.” Id. at 785. If that interest satisfies enhanced scrutiny, corporations can satisfy Unocal simply by following each other towards increasingly onerous bylaws. Just a few law

firms could immunize boards’ self-interested election regulation by advising their clients to adopt the same bylaws—rendering them all “modernized” together. Legitimacy cannot follow from modernization. Rock agreed, noting that

modernization is “an entirely factual question” that is “a very different question” from whether “a bylaw comport[s] with Delaware law.” Id. at 819. The Court should take him at his word.

31

Advice of Counsel Theory. Defendants repeatedly cite “the assistance of

counsel.” See DPTB at 42; 61. But advice of counsel is only as good as the purpose it serves. Here, Defendants relied on counsel to implement a defensive mechanism through maximally onerous bylaw revisions. Defendants then looked to the

same counsel to determine whether the target of those revisions (Kellner) failed their requirements. And to ensure failure, counsel moved the goal posts midgame by amending the D&O Questionnaire after Kellner requested it. Equels Tr. 580-84; JX 0821; JX 0834; JX0841. In short, counsel served a self-interested purpose, and the Board could not apply the Bylaws Amendments they adopted. Only counsel could do so.

This goes far beyond “advice of counsel.” Typically, reliance on outside expertise meets approval where experts provide factual

predicates that establish justification for board action, such as where investment banks advise on the fairness of a transaction. See Unocal, 493 A.2d at 950, 956-57. Defendants cite no case where a

Delaware court deferred to the legal judgment of a litigant’s attorney.

32

In the case Defendants cite (DPTB at 42), then-Vice Chancellor, now- Chancellor McCormick

rejected the proposition Defendants advance: “If the threat is not legitimate, then a reasonable investigation into the illegitimate threat, or a good faith belief that the threat warranted a response, will not be enough to save the

board.” Williams, 2021 WL 754593, at *22. Likewise, a lawyer cannot absolve the board from “selfish [and] disloyal” acts (Coster II, 300 A.3d at 672), by ratifying them and certainly not by advising on how to make them

optimally obstructionist. After all, corporate lawyers have “views that are sincerely held that also correspond to the interest of [their] clients.” Rock Tr. 820. Defendants cannot absolve their self-serving motives by pointing to the

individuals who serve those same motives. See Williams, 2021 WL 754593, at *40.

| |

b. |

The Bylaw Amendments Are Not Reasonable in Relation to Any Cognizable Interest |

Defendants cannot prove their “response to [a] threat was reasonable in relation to the threat posed and was not preclusive or coercive to

the stockholder franchise.” Coster II, 300 A.3d at 672-73. Even if a cognizable “threat” existed, the Bylaw Amendments went well beyond what was necessary to address it.

Enhanced scrutiny can be satisfied only where a board proves it is “properly motivated.” Id. at 673. Plaintiff’s Pre-Trial Brief (“PPTB”) demonstrated that the Bylaw Amendments amount to vote suppression (PPTB at 38), and trial evidence bore that out.

33

Tailoring Under Disclosure Theory. Even if a cognizable threat existed to justify a

valid disclosure interest, the Bylaw Amendments are not properly tailored to meet it. Defendants point to the 2022 Jorgl effort, but nothing in that experience justifies the extreme election overhaul of March 2023. Defendants point to isolated

prompts, such as the requirement to list purported “alias” names in response to difficulties researching Rice (Equels Tr. 529),3 and the clarification of AAU disclosure in response to an

argument that “Tudor didn’t have to be disclosed because … he was involved early and then dropped away” (id. at 718). Even assuming these concerns were valid, they have no logical connection to the dramatic revisions

ultimately adopted.

The Unocal inquiry looks to “all of the circumstances” (Phillips v. Insituform of N. Am.,

Inc., 1987 WL 16285, at *7 (Del. Ch. Aug. 27, 1987)), so the Bylaw Amendments cannot be taken apart and analyzed one by one. Viewed in their entirety, the Bylaw Amendments are “overreaching” and “contain numerous provisions that

are exceedingly uncommon, irregular and contrary to the spirit of shareholder democracy.” Freedman Tr. 848-49. They were “designed to make it as expensive and difficult as possible to be complied

with and to leave the door open for … fighting over whether a stockholder delivered a valid nomination notice.” Id. To obtain alternative names and “aliases” and to clarify the scope of AAU

| 3 |

Defendants presented no documentary evidence regarding any confusion about any individual’s identity. It

is neither uncommon nor deceptive for people to go by a middle name instead of his a name. Rice went by his middle name, Michael, instead of his Hebrew first name, Yehuda. AIM’s purported need to identify “alias” names is a sham and

slightly offensive. |

34

disclosure, Defendants did not need the excessive bylaw they adopted. By stacking requirement upon requirement, sentence upon sentence, definition upon definition, Defendants wove a web designed

not to be unwoven—and certainly not by specific stockholders Defendants had in mind during the weaving. Equels Tr. 624 (amendments were “in response to the 2022 events”).

Moreover, no trial evidence justifies most new provisions, including those requiring disclosure of family-member information, the 10-year disclosure window in the Consulting/Nomination Provision, or any of the more onerous provisions that are analyzed above. Defendants do not even attempt to justify these provisions by reference to threats to

AIM, much less from the 2022 experience. And Defendants certainly do not explain how adopting them together, on a proverbial rainy day, is “only what is necessary to counter the threat.” Coster II, 300 A.3d at 673.

Tailoring Under Modernization Theory. Even if AIM had a compelling interest in keeping up with the corporate Joneses, that would not

save the Bylaw Amendments, which are “exceedingly uncommon,” JX0985 ¶¶24-25; Freedman Tr. 832, 841-42.

35

That is undisputed. Defendants looked to Rock to substantiate their assertion that the Bylaw

Amendments “conform to market practice.” DPTB at 2. But he did not examine their text. He examined a few of the Bylaw Amendments by category because defense “[c]ounsel asked [him] to examine [only] four provisions.” Rock Tr. 784.

He did not consider whether the revisions, taken as a whole, modernized AIM’s bylaws. Id. at 822. Nor did he address the egregious Bylaw Provisions that Freedman criticized. JX0985 at ¶¶ 47, 81-98 & Ex. C.

Rock admitted that the 24-month lookback

period “is not the current market practice,” id. at 807, and that the Known-Supporter Provision “doesn’t appear in any of the 18 bylaws that [he] looked at from March of 2023” (id. at 792).4 He defended the latter (and the 13D Provision) as “state of the art,” by which he meant: “it’s spreading” (id. at 801-02). Even

taken at face value, those findings do not support a modernization Interest. Through these provisions, AIM far exceeded, rather than matched, common practice. Defendants cannot justify restricting the stockholder franchise on this basis.

Defendants’ modernization argument flounders even as to provisions Rock labels “ubiquitous.” While AAU provisions are common,

AIM’s 2016 bylaws included one. Rock admitted the bespoke 2023 AAU Provision does not reflect market practice. Rock Tr. 809-10. The same is true of other provisions Rock analyzed. “[T]he devil is in

the details.” Freedman Tr. 835. But Defendants do not justify the details. Defendants’ modernization theory is thus illegitimate and cannot justify what they did.

| 4 |

It also does not appear in the Rejection Letter and cannot be a basis for rejection. See PPTB at 56-57. |

36

| |

c. |

The Bylaw Amendments Are Draconian and Impermissibly Vague |

The Bylaw Amendments are also draconian and unreasonably vague. See Unitrin, Inc. v. Am. Gen. Corp., 651 A.2d 1361, 1387 (Del. 1995).

As Plaintiff’s pretrial brief explained (PPTB at 39-44), the Bylaw Amendments “fundamentally restrict[] proxy contests” (Chesapeake Corp. v. Shore, 771 A.2d, 333-34 (Del. Ch. 2000)), and compel stockholders “into voting a particular way” (Mercier v. Inter-Tel (Del.), Inc., 929 A.2d 786, 810-11 (Del. Ch. 2007)), by ensuring that only Defendants are on the ballot.

Defendants contend that

compliance is no problem: “[s]tockholders of public corporations who seek to nominate director candidates successfully comply with similar advance notice bylaws regulatory.” DPTB at 39. But that assertion does not speak to the

unprecedented scope of AIM’s bylaws or to what they require. The Bylaw Amendments are so sweeping and expansive as to require untold disclosures from anyone with meaningful business experience—i.e., anyone who would pose an

electoral threat to Defendants. For example, the interplay of the various terms— such as “acting in concert” in the definition of “Stockholder Associated Person” and Sections 1.4(c)(1)(D) and 1.4(c)(1)(E)—creates a

“daisy chain” effect. “It gloms on … the daisy-chain concept that operates to aggregate [persons] even if members of the group have no idea that the other [persons] exist.” Williams, 2021 WL 754593, at *37.

37

Further, the Bylaw Amendments are so vague that Defendants can reject notices at will by

manufacturing perceived omissions against convoluted text, (Freedman Tr. 838-40), including a 1,099-word run-on sentence. This

Court need no longer merely “envision an advance notice bylaw with so broad a reach that it mandated the disclosure of mere discussions among stockholders.” Jorgl, 2022 WL 16543834, at *16. That is what the Bylaw Amendments do.

| |

B. |

The Court Should Grant Relief from the Bylaw Amendments |

Plaintiff’s pretrial brief demonstrated (PPTB at 44) that board actions in violation of fiduciary duties are “of no force and

effect.” Black v. Hollinger Int’l Inc., 872 A.2d 559, 564, 567 (Del. 2005); Crown EMAK P’rs, LLC v. Kurz, 992 A.2d 377, 398 (Del. 2010). As a result, AIM has no advance notice bylaw, and Kellner’s slate should be

placed on the 2023 ballot.

38

| |

1. |

This Is a Facial Challenge |

Defendants counter with the perplexing, and ultimately irrelevant, position that Plaintiff’s arguments “are not facial

challenges” but “as-applied challenges.” PPTB at 34. But the case they cite, Delaware Board of Medical Licensure &

Discipline v. Grossinger, 224 A.3d 939 (Del. 2020), rejects their argument, holding that a facial challenge proposes contested action

“is not valid under any set of circumstances.” Id. at 956. That is the case here: because Defendants adopted on a rainy day the Bylaw Amendments in violation of their fiduciary duties, they are “of no force and effect.”

Black, 872 A.2d at 564. They cannot be applied under any circumstance. See, e.g., Williams, 2021 WL 754593, at *40 (declaring poison pill “invalid” for all stockholders where it failed enhanced scrutiny). Defendants

appear to believe that, because liability requires analysis of circumstances, the challenge must be as-applied. But Grossinger explained that a facial challenge turns on the scope of relief, not on

whether the arguments for liability “target only [the plaintiff’s] particular situation.” 224 A.2d at 957. That is the case here.

In any event, the point is semantic. Defendants note that the Court must look past “labels.” DPTB at 34. So the Court could not

“reject[]” this challenge for mislabeling (id. at 35), but rather decide it under the label it deems accurate and afford relief at least to Kellner and his nominees.

39

| |

2. |

AIM’s Prior Bylaws Are No Longer in Effect |

Defendants also claim, in an undeveloped footnote, that a ruling in Kellner’s favor would revert AIM to its prior bylaws, which would

support Defendants’ rejection of the Notice. DPTB at 39 n.13. But the “[c]asual mention” of a theory does not properly preserve it. Roca v. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 842 A.2d 1238, 1242 (Del. 2004).

It is a mystery why AIM would revert to bylaws its Board repealed and what support the prior bylaws would provide to the Notice rejection.5 Moreover, the Board is limited to the rationale it

offered when it rejected the Notice. See CytoDyn, 2021 WL 4775140, at *21. The Board never found that the Notice violated the 2016 bylaws and cannot assert that now.

| II. |

THE NOTICE COMPLIES WITH THE BYLAW AMENDMENTS |

Even if the Bylaw Amendments were valid (they are not), the Board cannot lawfully reject the Notice because it satisfies them. “The bylaws

of a Delaware corporation constitute part of a binding broader contract among the directors, officers and stockholders formed within the statutory framework of the Delaware General Corporation Law.” Hill Int’l, Inc. v. Opportunity

P’rs L.P., 119 A.3d 30, 38 (Del. 2015). The Court should employ “principles of contract interpretation,” Brown v. Matterport, Inc., 2022 WL 89568, at *3 (Del. Ch. Jan. 10, 2022), aff’d, 2022 WL 2960331 (Del.

July 27, 2022) (ORDER), and afford the text its “commonly accepted meaning,” Hill Int’l, 119 A.3d at 38. Ambiguity should be resolved “in favor of the stockholder’s electoral rights.” Id.

| 5 |

Rainbow Mountain, Inc. v. Begeman, 2017 WL 1097143 (Del. Ch. Mar. 23, 2017) does not support

Defendants’ position. In Rainbow Mountain, the Court found the relevant board lacked a quorum when it amended the company’s bylaws. Id., at *10. Because the board did not follow proper formalities when amending the bylaws,

the original bylaws remained. Id. That did not occur here. |

40

| |

A. |

The Notice Satisfies the AAU Provisions |

The AAU Provision required disclosure of all AAUs, “written or oral, and including promises,” that the “Holder,” any

“Stockholder Associated Person,” and the nominees have with each other or persons “acting in concert” with them “existing presently or existing during the prior twenty-four (24) months relating to or in connection

with” AIM director nominations. JX0686 at 2. The terms “arrangement” and “understanding” are not defined and, under their lay meanings, reach “any advance plan, measure taken, or agreement—whether explicit,

implicit, or tacit— with any person towards the shared goal of the nomination.” Jorgl, 2022 WL 16543834, at *12. But “the occurrence of discussions, a prior business or personal relationship, or an exchange of information is

not alone sufficient to show an ‘arrangement or understanding.’” Id. The Notice accurately disclosed AAUs relating to (i) the 2022 proxy efforts, (ii) discussions in late 2022 regarding AIM; (iii) preliminary

discussions in 2023 regarding a potential proxy contest and (iii) Kellner’s 2023 nominations.

41

| |

1. |

No Undisclosed 2022 AAUs |

Defendants claim the Notice “did ‘not mention[] or acknowledge[]’ AAUs that Chioini, Kellner, and Deutsch have and had among

themselves and others, including Tudor, Xirinachs, Lautz, Jorgl, Rice, Tusa, and River Rock” in 2022. DPTB at 48. Trial showed the opposite.

As a preliminary matter, Defendants did not call Tudor at trial, despite making him their conspiracy’s fulcrum and naming

him 104 times in their pre-trial brief.6 Defendants also called none of the other purported conspirators. Defendants proffer only self-serving

interpretations of cherry-picked correspondences from the so-called “conspirators,” which is no substitute for testimony. In any event, their interpretations fail.

Tudor. Kellner’s Notice accurately addressed Tudor. In it, “[e]ach of Messrs. Kellner, Deutsch and Chioini acknowledge[d]

relationships with Mr. Tudor.” JX0785 at 8. Specifically, it discloses that:

| 6 |

Defendants cannot rely upon the depositions of Rice (JX0393), Jorgl (JX0402), Rodino (JX0403), Equels (JX0417),

Ring (JX0418), Lautz (JX0420), Tusa (JX0421), or Tudor (JX0423), taken in the Jorgl matter for the truth of matters asserted (the “Disputed Witnesses”). Plaintiff objected to those exhibits (see Dkt. 253) under Ct. Ch. R. 32

and D.R.E. 802. Under Rule 32(a) testimony “may be used against any party who was present or represented at the taking of the deposition or who had reasonable notice thereof” Ct. Ch. R. 32 (emphasis added). Kellner, a non-party, was neither “present” nor “represented” in Jorgl. “When not used for a purpose authorized by … Rule 32, a deposition transcript is hearsay.” ACP Master, Ltd.

v. Sprint Corp., 2017 WL 75851, at *3 (Del. Ch. Jan. 9, 2017). Defendants have not established any exception to hearsay. |

42

| |

• |

|

Chioini first met Tudor when Tudor provided consulting services to Rockwell Medical and has maintained a business

relationship with him for years (Chioini Tr. 69); |

| |

• |

|

Deutsch has known Tudor since they worked together in the early 2000s, and they have discussed their frustration

with AIM’s stock performance (Deutsch Tr. 161-63); |

| |

• |

|

“Mr. Chioini’s first involvement with the Company came when Mr. Tudor recommended Mr. Chioini

as a nominee” to Walter Lautz (“Lautz”) (JX0875 at 8); |

| |

• |

|

Kellner met Tudor through Deutsch and has communicated with Tudor regarding AIM (Id.; Kellner Tr. 230-31); and |

| |

• |

|

“Mr. Tudor may have been aware of what was going on at the time and possibly viewed the nominations of

Mr. Chioini and Mr. Rice by Mr. Jorgl as a continuation of any prior efforts he may have had” (JX0875 at 8-9). |

43

While Tudor introduced Chioini to Lautz regarding Lautz’s failed April 2022 nomination

attempt, Tudor was not “involved in the 2022 proxy contest” with Jorgl. Chioini Tr. 38, 69; Tudor Tr. 454, 458. Tudor testified that, after the Lautz nomination failed, he “tried to think if [he] knew anyone and [he] didn’t”

(Tudor Tr. 445), “didn’t find anybody” to front the $150,000 (id. 450), and “assumed [another nomination] was never going to happen” (id. 445). In June 2022, Tudor floated the idea of a nomination by Deutsch,

(see DPTB at 11; see JX0265 at 1), that never materialized. Deutsch Tr. 188.

Defendants cite 2022 communications between

Chioini, Deutsch, and/or Kellner with Tudor as evidence of Tudor’s involvement. See e.g., DPTB at 7, 10. But the communications (i) were disclosed, and/or (ii) do not show an AAU. For example, Defendants cite a Spring 2022

videoconference invitation forwarded from Chioini to Tudor as “proof” of his involvement. JX0240. But that meeting never occurred. Chioini Tr. 73. And the Notice discloses that “Mr. Chioini . . . communicated with . . .

Mr. Tudor in June 2022 to see if [he] would be willing to nominate Mr. Chioini and Mr. Rice” to AIM’s board. JX0875. Discussions are not AAUs. Jorgl, 2022 WL 16543834, at *11. Defendants read too much into preliminary

communications between Chioini and Tudor. See Chioini Tr. 70-79.

Similarly, no one denies

Kellner, Tudor, and Deutsch “have communicated” about AIM (Deutsch Tr. 173), that they “wanted AIM’s board to take action on initiatives” (id.), and that Kellner had June 2022 “discussions” with Tudor about

Tudor’s small stake in AIM (Kellner Tr. 316-17). Stockholders may talk about a company, and their frustrations with management, without an AAU. Regardless, the Notice discloses that Deutsch and Kellner

communicated with Tudor regarding AIM in 2022. JX0785 at 8.

44

Moreover, most of Tudor’s 2022 communications with Deutsch and Kellner were in his

capacity as an analyst (Deutsch Tr. 184-89, 206), with knowledge of Ampligen and the “potential for the drug” (Kellner Tr. 221; see also id. at 271-72;

JX0205). Kellner consults hundreds of analysts a year; Tudor was just one. See Kellner Tr. 230. One of Kellner’s hand-written notes on a Tudor memo asked: “who wrote this?” JX0205; see Kellner Tr. 292 (“I

didn’t know who wrote it”). On another, Kellner had to remind himself: “Franz / Hedge Fund Guy.” JX265. Another was filled with questions marks about AIM’s assertions concerning Tudor. See JX0278; Kellner Tr. 325.

These communications (viewed in light of Kellner’s questions) plainly do not amount to an AAU.

Xirinachs. Defendants next

allege undisclosed 2022 AAUs about Michael Xirinachs (“Xirinachs”). JX0918 at 4. But the Notice discloses Xirinachs was a party to the 2022 Group Agreement, along with the Agreement’s terms, and contains a “Statement

Regarding Mr. Xirinachs.” JX0875 at 6-8. Defendants’ quarrels with that thorough disclosure fail.

45

First, Defendants quibble with “when” Xirinachs first entered AAUs

with Chioini, JX0918 at 4, arguing that must have occurred “well before July 8, 2022” (JX0918 at 4), because, in Jorgl, Chioini withheld certain communications involving Xirinachs and BakerHostetler on privilege and “common

interest” grounds. DPTB at 12 (citing JX0990; JX1000; JX1020; JX0392), see also id. at 49. That proves nothing. Chioini testified that he tried to recruit Xirinachs for the 2022 effort, Xirinachs wanted more information, Chioini Tr. 85-86, 77, and Chioini began including Xirinachs on calls with BakerHostetler as a prospective client, Harrington Tr. 423-27. Communications with prospective clients are

privileged, as are those communications between an attorney, a client, and a prospective client involving a common interest. See PennEnvironment v. PPG Indus., Inc., 2013 WL 6147674, at *5 (W.D. Pa. Nov. 22, 2013) (finding communications

between attorney, client, and third-party prospective clients were protected under common interest privilege); DLRPC 1.18. And, whatever the merits of that privilege assertion, discussions with a lawyer, prior to entering a group agreement, do not

arise to an AAU. In short, Xirinachs did not decide to join the group until after July 8, 2022.

46

Second, Defendants claim false and misleading disclosures, alleging Chioini

and Xirinachs “never truly intended that River Rock would be a funding source” and that “the plan all along was for Mr. Xirinachs to secretly channel funds through River Rock in order to conceal his involvement and funding

commitment.” JX0918 at 4- 5; see DPTB at 15-17. That is false. Again, “for several weeks” prior to July 8, 2022, Chioini “was trying to get Mr. Xirinachs to join

the group . . . to help fund the proxy contest,” but was not initially successful. Chioini Tr. 36 (emphasis added). On July 11, 2022, Chioini spoke to Tusa—not Xirinachs—“to discuss potential funding,”

and, on July 27, 2022, Chioini, Jorgl, Rice and River Rock entered the 2022 Group Agreement. JX0875 at 6. It initially provided that River Rock would fund the Jorgl nomination efforts, but “Mr. Tusa’s financial circumstances