By Leslie Scism

When Steven A. Kandarian was named chief executive officer of

MetLife Inc. back in 2011, it looked like smooth sailing ahead. The

global financial crisis was over.

The problem was, the bond market never got the memo. Interest

rates fell to never-before-seen levels, causing headaches for

MetLife and other life insurers. The low yields depressed their

interest income, a big part of their bottom line.

What's more, the Dodd-Frank regulatory overhaul ensnared

MetLife. A new panel created by that law designated the company

"systemically important" and subject to heightened oversight. Mr.

Kandarian successfully sued the U.S. government to escape the

designation.

As low rates persisted, in 2017 he spun off a fifth of the

company -- its historic core selling life insurance to American

families -- in part because the products required so much

capital.

The 67-year-old executive is leaving MetLife April 30. He stayed

two years past the insurer's customary retirement age to complete

the spinoff and get succession underway. One of his deputies,

Michel Khalaf, is succeeding him.

From his 56th-floor conference room in the MetLife building

above Grand Central station in midtown Manhattan, Mr. Kandarian

spoke about his eight years at the helm. Here, condensed and edited

excerpts from that conversation:

WSJ: What decision was tougher: suing the U.S. government to

challenge MetLife's designation as a systemically important

financial institution, or spinning off the individual-focused

operations symbolized by MetLife's long-time Snoopy logo into

Brighthouse Financial Inc.?

Mr. Kandarian: The spinoff of Brighthouse was the more difficult

decision. It was an emotional one. There was a lot of attachment to

that business in our company, with our employees, former employees,

customers and so on. The business dated back to 1868.

The spinoff enables our shareholders and investors in general to

make a choice on both components of our business. The U.S. retail

business has a different dynamic than the rest of our U.S. business

focused on institutional clients and our international

businesses.

The SIFI decision was more straightforward. In our view, it was

an existential decision to our company: If we were designated, and

if the Federal Reserve wrote capital rules for enhanced capital and

regulation that put us on an unlevel playing field, it would make

it difficult for us to remain as one company. We would have to

ultimately give serious consideration to breaking up the company --

and for no good reason, we felt.

WSJ: Are you saying that divestitures beyond the Brighthouse

spinoff might have occurred?

Mr. Kandarian: Brighthouse was 20% of the company. You would

have to shrink the business significantly to get under whatever

level FSOC felt hit their screen. It would have been a significant

deconstruction of the company, beyond just the U.S. retail

business.

WSJ: As it turned out, after challenging your designation by the

Financial Stability Oversight Council, Donald Trump was elected

president and began a rollback of Dodd-Frank. Two peers -- American

International Group Inc. and Prudential Financial Inc. -- were

"de-designated" thanks partly to Trump appointees to FSOC. Do you

have second thoughts about the amount of money and management time

you spent on the effort?

Mr. Kandarian: We felt that under Dodd-Frank we were not

systemically important by the definition of the law, which is

basically: Would material financial distress of MetLife pose a

threat to the financial stability of the U.S.?

AIG and GE [ General Electric Co., another SIFI] dramatically

changed their businesses, and I think that was a major factor in

their de-designations. But Prudential did not. I don't think

Prudential would have been de-designated had we not contested our

designation in court and won.

WSJ: In other words, you helped a major rival?

Mr. Kandarian: We brought our case forward on behalf of our

customers, our shareholders and employees of MetLife, and

Prudential did benefit from that. We are still waiting for the

thank-you letter from Prudential.

WSJ: You walked a fine line in pushing your case against the

government and not being seen as too antagonistic. It has been

clear that the SIFI designation rankled you. Talk about that.

Mr. Kandarian: I want to be careful here. But I've been thinking

about this for a while and want to lay it out.

The federal financial regulators came under a great deal of

scrutiny soon after the financial crisis broke out for having

failed as regulators in certain cases....I think the SIFI

designations for ourselves and Prudential were largely driven by

the need of these regulators to restore their reputations and

rebuild their standing in certain circles in Washington. It was

more a political decision than an economic one.

We have an interest in an appropriately rigorous regulatory

regime for our industry. We don't have in interest in gratuitous

regulation or capital charges that are well beyond what is

necessary for a solvent system, or a regulatory regime that puts

companies on unlevel playing fields that make it difficult of

impossible to compete. That is what the fight was about.

WSJ: What do you want to be remembered for from your tenure?

Mr. Kandarian: I think probably central to my tenure of CEO is

the de-risking of our company.

When I was chief investment officer we de risked the asset side

of our balance sheet prior to the financial crisis. We sold Peter

Cooper Stuyvesant Town residential complex in New York City for

$5.4 billion in 2006. That asset at that point comprised roughly

half of our real-estate equity portfolio. I felt that was a

too-concentrated position.

We also sold down the riskiest portion of our subprime

mortgages. And we sold approximately $8 billion of credit assets

that we felt would be most vulnerable in a consumer-led

recession.

I focused a great deal on the liability side after becoming CEO.

We exited some products entirely like long-term-care insurance, and

reconfigured others to make them less capital intensive and less

sensitive to assets rolling off our balance sheet and perhaps

having to be reinvested at lower rates in the future.

WSJ: MetLife has committed to large share buybacks with its

excess capital. It seems every day there is more criticism of

buybacks. What can you say to people in this camp who think you are

doing something wrong?

Mr. Kandarian: Some people have set this up as an either/or:

Either you provide for your employees or you do shareholder

repurchases. We do both. We provide health benefits to all of our

employees. We provide sick leave to all of our employees. We have a

$15 minimum wage. Everybody gets $75,000 or more of life insurance.

And we provide a traditional pension to all of our employees.

At the same time we need to take care of those who provide us

capital to run this business. Many of those are just ordinary

people who are investing their retirement funds through

institutional investors.

WSJ: MetLife shares have underperformed other big insurers

during the period you were CEO. Anything you wish you had done

differently?

Mr. Kandarian: It takes time to turn a big ship like MetLife.

I'll give you one example. Sales that were made more than three

years years ago represent 85% of our current bottom line. Because

of the long-term nature of our liabilities, they stay with you for

many, many years. In some cases, for many decades.

We addressed that by spinning off Brighthouse to some degree.

But we still retain a significant number of liabilities related to

our U.S. retail business.

We could have pursued shorter-term actions that may have driven

up near-term earnings but could have exposed the company to losses

in the future.

We know that to get better stock performance, we have to deliver

clean quarters, show we can grow profitability and return capital

to our shareholders when we can't use the capital more

profitably.

WSJ: What's next? Will you run another company?

Mr. Kandarian: It is possible if I do that it would be with a

privately held company.

I think the public company arena has become more difficult to

operate in. The short-term nature of how investors look at things

is one issue, and there are a lot of things today that CEOs didn't

have to focus on as much in the past.

There are now roughly half as many public companies as two

decades ago. That is an unfortunate statistic from the point of

view of providing investment opportunities for ordinary Americans

as they prepare for retirement. The private markets are less

accessible to them than the public markets and the public markets

are shrinking. So that's a regrettable consequence of short-term

pressure on public companies.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 25, 2019 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

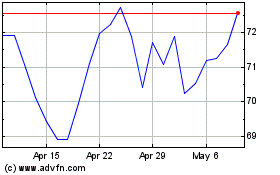

MetLife (NYSE:MET)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

MetLife (NYSE:MET)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024