By Rachel Louise Ensign

Americans are parking more money with the biggest banks than

ever before, cementing the firms' dominance of the financial

industry less than a decade after the crisis.

The three largest U.S. banks have added more than $2.4 trillion

in domestic deposits over the past 10 years -- a 180% increase --

according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of regulatory data.

That amount exceeds what the top eight banks had in such deposits

combined in 2007.

The outsize gain began when the trio of lenders -- JPMorgan

Chase & Co., Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co. --

did huge deals during the crisis. Their heft has continued to

increase in recent years as consumers opt to put their money at the

behemoths over smaller U.S. banks.

While the crisis led many to question whether banks had grown

too large, the lead of the biggest lenders has only widened. At the

end of 2007, the three banks held 20% of the country's deposits. By

the end of 2017, they held 32%, or $3.8 trillion.

It marks a new phase of consolidation in the banking industry --

one driven first by the deals and then by customers' attraction to

the digital tools and ubiquitous locations of the biggest

banks.

Last year, about 45% of new checking accounts were opened at the

three national banks, even though those lenders only had 24% of

U.S. branches, according to research by consulting firm Novantas.

Regional and community banks, by contrast, had 76% of branches but

only got 48% of new accounts, the firm said.

These customers, who tend to be younger, are valuable to banks

because they often provide more business later on by, for instance,

taking out a mortgage or opening a brokerage account.

Before online and mobile banking became popular following the

financial crisis, these consumers generally opened a new account at

the bank with the nearest branch, no matter the size of the

institution, said Andrew Frisbie, executive vice president at

Novantas.

But now that many banking transactions are done online or

through smartphones, these customers are increasingly picking

national banks because of their well-known brands and the

perception that their technology is better, Mr. Frisbie said.

Large banks' deposit growth is a major advantage because it

provides the banks with a growing base of cheap financing that can

be used to make loans. It also allows them to avoid paying higher

interest rates to depositors, which disappoints savers but boosts

the firms' profit margins.

"The biggest banks are winning," wrote Tom Brown, CEO of hedge

fund Second Curve Capital, last month. "Small banks should be very

concerned."

Hundreds of smaller banks have been merging. At the end of 2017,

the number of commercial banks in the U.S. fell below 5,000 for the

first time since the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. started

keeping track in the 1930s. The number peaked in 1984 at about

14,500 banks. Deposits at banks other than the three largest grew

49% from 2007 to 2017.

The biggest banks keep growing despite limits that prevent them

from buying smaller rivals. All three now each control at least 10%

of the nation's deposits, the level where an acquisition ban kicks

in to promote competition among lenders. Even Wells Fargo's

domestic deposits have grown markedly since the crisis, despite a

sales-practices scandal that hit the bank in 2016.

The continued gains for the big banks show just how good they've

become at attracting deposits. By growing without the mergers they

have relied on in the past, the banks also don't have to contend

with the 10% limit.

Some of the deposit growth comes from businesses parking their

money in bank accounts that earn no interest. That funding is often

considered less valuable because it is seen as likelier to leave as

rates continue to rise.

But the biggest chunk of deposits is held in the banks' retail

units, which hold money consumers leave in their checking and

savings accounts, according to bank filings. These deposits, which

are considered "sticky" or less likely to leave, have become even

more important because of postcrisis rules.

The biggest banks have also improved customer satisfaction

ratings that had been damaged by the financial crisis and spike in

home foreclosures. And they are persuading current customers to

leave more money with them. For instance, the average checking

account balance at Bank of America has grown to about $7,000 from

$2,000 in 2007.

Prohibited from doing deals, JPMorgan and Bank of America are

planning to keep growing -- by opening branches in major U.S.

cities where they currently have none. Bank of America has opened

or announced plans to open around Denver, Indianapolis and other

cities. JPMorgan hasn't named the 15 to 20 new markets it is

entering, but analysts think they could include Boston, Washington,

D.C. and Philadelphia.

The strategy could steal business from Wells Fargo, which is

struggling to move past its various regulatory issues. It could

also accelerate deposit-gathering problems for smaller banks, said

Mr. Brown of Second Curve Capital.

And that can lead to other issues, from slowing loan growth to

dwindling fees from other relationships. The risk for small banks,

he said, is that "this is a slow death."

Write to Rachel Louise Ensign at rachel.ensign@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 22, 2018 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

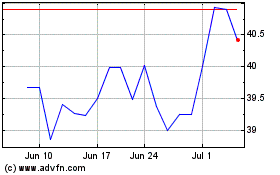

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Aug 2024 to Sep 2024

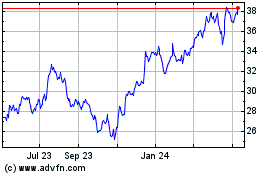

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Sep 2023 to Sep 2024