By Denise Roland and Peter Loftus

Insulin prices are soaring, creating pain for patients whose

lives depend on the injectable drug -- yet most of the revenue from

the increases isn't going to the drug manufacturers, it is largely

being collected by middlemen.

The major manufacturers of insulin -- Eli Lilly & Co. of

Indianapolis, Novo Nordisk A/S of Denmark and Sanofi SA of France

-- are collecting about the same or less than they did several

years ago. The price increases reflect the growing role of

middlemen known as pharmacy-benefit managers who collect a fee

based on list prices.

This convoluted payment system for drugs in the U.S. encourages

high list prices and steep behind-the-scenes discounts. That

formula offers some bill payers lower overall costs while uninsured

patients and those with certain health plans pay more.

At the same time, higher overall costs are encouraging U.S.

health insurers and employers to make patients contribute more to

their health care. In part, their use of higher deductibles

contributes to the cost shifting to patients. Higher drug list

prices mean those patients most exposed to the price increases pay

more before their plan coverage kicks in.

"Prices for these products have increased," said Aaron

Kesselheim, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School who

has researched insulin costs. "It's also the case that there are

more patients under high-deductible health plans and who may have a

greater copay and coinsurance, and they're being exposed to a

larger share of the prices as well."

U.S. list prices for top-selling insulins -- Sanofi's Lantus,

Eli Lilly's Humalog and Novo Nordisk's Novolog -- have more than

doubled since 2011, according to data provider Truven Health

Analytics. Drugmakers are responsible for raising list prices, even

if they recently haven't gained much from the process. Lantus, the

top-selling insulin, now costs $248.51 a vial, up from $114.15 in

2011. A Sanofi spokeswoman said the company hasn't increased its

list price in nearly two years.

Net prices, or what drugmakers retain after discounts, have

stayed the same or fallen in the last two years as the

pharmaceutical companies compete to offer ever-deeper discounts to

stay on the preferred drug lists at insurers and the PBM

middlemen.

The reason drugmakers sharply raise list prices without a

corresponding increase in net price is that PBMs demand higher

rebates in exchange for including the drug on their preferred-drug

lists, said Enrique Conterno, president of Lilly's diabetes

business.

Eli Lilly has raised the list price of Humalog -- to $254.80 a

vial, more than double the 2011 price. After rebates and discounts,

Lilly on average in the U.S. collects less for its Humalog insulin

than it did in 2009, Mr. Conterno said.

PBMs get to keep a portion of the rebates off list that they

negotiate -- though they pass the rest on to clients -- and the

administrative fees that PBMs collect from manufacturers are based

on percentages of the list prices.

However, counters Steve Miller, chief medical officer of Express

Scripts Holding Co., the largest U.S. PBM, "We never tell

pharmaceutical companies we want high sticker prices. We want a low

net price."

He acknowledges that "certain patients get caught in the middle

of this, and we have got to figure out how to put guard rails

around that," such as setting a maximum pharmacy price.

For Sanofi's Lantus, the average U.S. net price fell by 17% in

2015 and is on track to fall a further 10% this year, according to

estimates by equity researchers at Sanford C. Bernstein & Co.

The firm expects the net price of Novo Nordisk's Levemir insulin to

fall 6% this year. Sanofi and Novo Nordisk have warned investors

that falling prices in the U.S. will hurt profit growth.

America's Health Insurance Plans, an industry trade group, said

drug companies control pricing, and when insulin prices rise,

"patients end up paying more -- regardless of what kind of

insurance plan they have."

Christie Tucker, a 45-year-old electrical contractor in Port

Angeles, Wash., said the bill for a six-week supply of insulin for

her son Preston has soared in the past two years.

When Preston was diagnosed, Mrs. Tucker paid $40 for a six-week

supply. But the cost jumped to more than $600 in January because,

instead of a fixed-dollar-amount copay, her insurance plan charges

30% of the pharmacy price of insulin, she said. Mrs. Tucker has

saved on some prescriptions using coupons but expects to pay $650

for the next refill.

High-deductible insurance plans are causing sticker shock for

many patients. About 23% of American workers with

employer-sponsored health plans have annual deductibles of at least

$2,000 a person, up from 7% in 2009, according to the Kaiser Family

Foundation.

Jeff Dunlop, a 41-year-old mental-health case manager in Winter

Haven, Fla., said he paid about $1,250 for a three-month supply of

Lilly's Humalog earlier this year. Mr. Dunlop, who was diagnosed

with Type 1 diabetes as a child, paid the full cost because his

family insurance plan -- offered by his wife's employer -- now has

a $4,000 annual deductible.

He can handle the cost for now but said he worries about the

future.

"There's a lot of people out there that just can't afford it,"

he said. "I'm one or two unfortunate circumstances away from being

in that boat. That's scary because I need that stuff to live.

Without it, I die."

Write to Denise Roland at Denise.Roland@wsj.com and Peter Loftus

at peter.loftus@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 07, 2016 18:01 ET (22:01 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

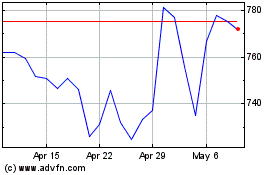

Eli Lilly (NYSE:LLY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Eli Lilly (NYSE:LLY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024