The potential sale of German power-production assets by a

Swedish state-owned company to a Czech buyer is stoking public

fears that German taxpayers could face a multibillion-euro bill for

underwriting the transaction.

Sweden's Vattenfall AB last fall invited bids for its German

coal-fired power plants and mining assets. Two Czech suitors,

Energeticky a Prumyslovy Holding, orEPH, and Czech Coal Group, said

they submitted binding bids to Vattenfall on March 16. The bids

could trump a proposal from a rival German suitor, the

municipality-owned utility Steag, according to people close to the

matter.

EPH and Steag declined to comment, while Czech Coal and

Vattenfall didn't respond to requests seeking comment.

Vattenfall's operations are under pressure from falling energy

prices. Buying the assets also brings responsibility for shutting

the mines over the coming decades, an expensive proposition.

Those huge financial burdens have prompted all the bidders to

ask Vattenfall to provide the assets with billions of euros in cash

for the sale to go through, these people said. Because it is

unclear whether the unit's current cash pile of slightly more than

€1 billion ($1.18 billion) will suffice, the move could effectively

mean Vattenfall would be paying a buyer to take the operations and

related liabilities off its hands.

The insiders said that the Czech companies aren't seeking as

much cash from Vattenfall as rival suitor Steag. The German firm

submitted a proposal together with Australia's Macquarie Capital

that foresees transferring the lignite mines and power stations

into a foundation, with Vattenfall forking out more than €2 billion

in cash, they said.

Yet some politicians voiced concern that the bidder with the

most attractive conditions might not be the best one for taxpayers,

because a low cash injection from Vattenfall means taxpayers could

end up footing the bill for shutting down the mines and plants.

"If investors like EPH are buying [Vattenfall's German lignite

operations], I see the risk that they won't take care of the costs

for shutting them down," said Annalena Baerbock, a member of the

Green party in the German parliament.

If the money set aside to cover future liabilities isn't

safeguarded, those bidders may take the profits from the lignite

assets, and then let them go bankrupt, she added. While Mrs.

Baerbock said she expected costs of more than €10 billion to shut

down these mines, bankers see the resulting costs at roughly €3.5

billion.

Regardless whether a Czech or German suitor succeeds in the

auction, lawmakers are aware of the possibility that taxpayers

could be on the hook.

"Vattenfall mustn't be able to rake in billions in profits and

leave the burden with taxpayers," said Klaus-Peter Schulze, member

of the German parliament for the ruling CDU party.

Winning political support for the deal is necessary because

Germany's regional governments are responsible for granting mining

licenses and thereby have an influence over the potential

buyer.

Germany aims to meet roughly 80% of its electricity needs with

renewable energy by 2050, giving green energy priority on grids.

This will gradually phase out coal-generated power, making mines

obsolete.

The country's consumers will spend around €23 billion to

subsidize producers of renewable energy this year, according to

German grid operator Tennet.

Because electricity prices in Germany are falling, the market

value of the renewable power generated will be at roughly €3

billion a year, meaning German net spending of roughly €20 billion

on renewable energy.

Vattenfall in October 2014 announced it would divest its German

lignite operations as part of its strategy to cut carbon emission

and boost renewable sources of energy. Since then, electricity

prices in Germany have dropped to around €22 per megawatt-hour,

compared with €35 in late 2014. The situation is troubling all

German energy producers.

Since late 2014, share prices of RWE AG and E. ON AG, the

country's largest energy producers, have fallen by 60% and 35%

respectively.

Amid the grim situation, politicians are worried that closures

could result in a sharp rise in unemployment in eastern Germany,

where jobless levels are higher than in the rest of the

country.

Vattenfall has 8,200 employees in its German lignite operations.

The activities recorded €2.3 billion in revenues in 2014.

In a similar situation, EPH in September last year said it might

shut its UK-based coal-fired power unit, at Eggborough, by the end

of this month.

It added the power station, which provides 4% of the UK's

electricity, "requires additional funding of roughly £ 200 million

over the next three years to continue generating power, which is

financially unsustainable for the 53-year-old plant."

In a surprising U-turn, EPH in February postponed the

foreclosure by one year after it secured a new energy contract from

the U.K. natural-gas and electricity network operator National Grid

PLC.

Write to Eyk Henning at eyk.henning@wsj.com and Jenny Busche at

jenny.busche@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 29, 2016 05:35 ET (09:35 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

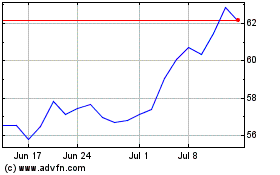

National Grid (NYSE:NGG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

National Grid (NYSE:NGG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024