Democrats Tussle Over Bill That Contributed to the Financial Crisis

February 11 2016 - 4:17PM

Dow Jones News

By Andrew Ackerman

WASHINGTON--When Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders square off

tonight at a debate in Wisconsin, expect more attention to an

unlikely source of friction between the leading Democratic

presidential candidates: a 15-year-old law barring regulation of

complex financial instruments at the heart of the 2008 financial

crisis.

For weeks, Mrs. Clinton has criticized the Vermont senator for

backing the 2000 Commodity Futures Modernization Act, which

prohibited U.S. policy makers from regulating derivatives. The

measure deregulated the types of mortgage-related swaps and other

derivatives that backfired during the crisis, contributing to the

collapse of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. and the near-collapse of

firms like American International Group Inc.

"You're the one who voted to deregulate swaps and derivatives in

2000, which contributed to the overleveraging of Lehman Brothers,

which was one of the culprits that brought down the economy," Mrs.

Clinton said at a Democratic debate last week.

Derivatives, including swaps, are used by banks and other firms

to hedge--or speculate--on everything from moves in interest rates

to the cost of fuel.

Mr. Sanders, who has made breaking up the biggest U.S. banks a

top policy goal, has yet to directly respond to the criticism,

saying nobody has fought harder against Wall Street-backed

legislation in Congress than he has.

Now one of his top aides says the senator's "yes" vote in 2000

was a mistake, and he blames the administration of President Bill

Clinton, Mrs. Clinton's husband. The Clinton administration was

aggressively supporting the legislation at the time, and Mr.

Clinton signed it into law. The former president, however, now says

he, too, received bad advice.

"It was a mistake to listen to the Clinton administration's

economic advisers who were so successful in pushing for this bill

that only four members of Congress voted against it," said Warren

Gunnels, a policy adviser to Mr. Sanders. He was referring to a

stand-alone House vote on the bill in October 2000, when Mr.

Sanders was a member of the House of Representatives. A similar

version of the bill eventually cleared both chambers of Congress

two months later after it was added to must-pass legislation

funding the federal government.

The fight over the 15-year-old legislation is the latest

illustration of how deep divisions over Wall Street have come to

define the presidential campaigns of the two leading Democratic

candidates. Mr. Sanders, citing what he sees as greed and

irresponsibility on Wall Street, has put forth proposals that would

reshape American finance, promising to break up the biggest banks

in his first year in office.

Mrs. Clinton has taken a more surgical approach. Her campaign

has developed more than two dozen ideas that form a web of

regulation, prosecution and taxation aimed at deterring what she

considers bad behavior.

Though once considered a long-shot candidate, Mr. Sanders

finished the Iowa caucuses in a dead heat with Mrs. Clinton, and he

decisively beat the former secretary of state in the New Hampshire

primary this week. The nominating contest now moves to South

Carolina and other southern states with large minority populations

where Mrs. Clinton's campaign is banking on a revival.

Mr. Gunnels said the criticism of Mr. Sanders's record is

"disingenuous" because the 2000 law had the backing of not only

Mrs. Clinton's husband but also Gary Gensler, a Treasury Department

official at the time who was intimately involved in advancing the

bill through Congress. Mr. Gensler is now the chief financial

officer of Mrs. Clinton's campaign.

"As soon as Sen. Sanders learned how bad this bill was he worked

to repeal it," said Mr. Gunnels. Mr. Sanders also led the

opposition to Mr. Gensler's 2009 nomination to head the Commodity

Futures Trading Commission--which gained authority to regulate

swaps after the crisis--because of Mr. Gensler's role in

spearheading passage of the 2000 law, Mr. Gunnels said.

Most Democratic lawmakers and liberal groups later cheered Mr.

Gensler's bare-knuckle approach to rule-making--a surprising turn

for the former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. executive and one-time

champion of deregulation. Despite that reputation, Mr. Gensler has

long been a target of Mr. Sanders, largely over high-profile CFTC

rules designed to curb bets on oil, gold and other commodities that

Mr. Sanders believes didn't go far enough to limit speculation. A

federal court eventually sent the rules back to the CFTC, ruling

the agency didn't do enough to justify their burdens.

For Mrs. Clinton, raising concerns about Mr. Sanders's voting

record allows her to deflect criticism that her own relationship

with Wall Street is cozy. She has accepted millions in donations

and speaking fees from large firms, but says she never changed a

view or a vote because of a contribution.

"I'm not impugning your motive because you voted to deregulate

swaps and derivatives," she said of Mr. Sanders at last week's

debate. "People make mistakes and I'm certainly not saying you did

it for any kind of financial advantage. What we've got to do as

Democrats is to be united to actually solve these problems. And

what I believe is that I have a better track record and a better

opportunity to actually get that job done."

Write to Andrew Ackerman at andrew.ackerman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 11, 2016 16:02 ET (21:02 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

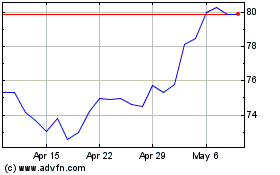

American (NYSE:AIG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

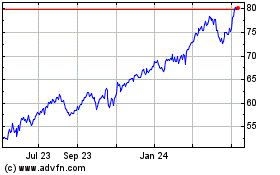

American (NYSE:AIG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024